A dance of vaporizing bodies, with a nod to butoh

NEW YORK — In his dances and in life, choreographer Kota Yamazaki believes that a person needs to be fluid, like water. As he said in a recent interview, “You have to keep flowing, so people of different backgrounds can have a freer exchange.” His wife and assistant, dancer and choreographer Mina Nishimura, added with a laugh, “It’s very Japanese.”

Posted — Updated

NEW YORK — In his dances and in life, choreographer Kota Yamazaki believes that a person needs to be fluid, like water. As he said in a recent interview, “You have to keep flowing, so people of different backgrounds can have a freer exchange.” His wife and assistant, dancer and choreographer Mina Nishimura, added with a laugh, “It’s very Japanese.”

Yamazaki’s company, the aptly named Fluid hug-hug, will display his philosophy in “Darkness Odyssey Part 2: I or Hallucination,” which is to have its premiere Wednesday at the Baryshnikov Arts Center. It’s the second work of a trilogy; the first, performed in Japan, was a tribute to Tatsumi Hijikata, a founder of Butoh.

In “Hallucination,” Yamazaki reconsiders Hijikata’s notion of Butoh as a “dance of darkness.” Instead, he focuses on the idea of the body as a black hole: It has the capacity to absorb all that it comes into contact with.

Not that “Hallucination” is Butoh. “I have that in my body,” Yamazaki, 58, said, “but it’s not the purpose of the work.”

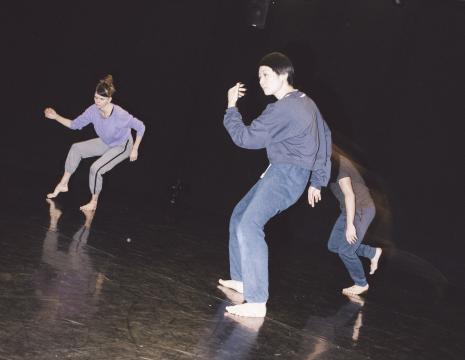

His new dance creates a fragmented world, in which the performers engage in continually shifting transformations. Making it, he said, he was most drawn to the idea of the fragile or vaporizing body. He also considered the writings of French philosophers Deleuze and Guattari and the tradition of Japanese goze music, which was performed by blind women.

For “Hallucination,” Yamazaki recruited dancer-choreographers from New York’s downtown scene to perform. Nishimura, 38, will be joined by Julian Barnett, Raja Kelly and Joanna Kotze. “I wanted to have an almost equal relationship with them,” Yamazaki said. “This journey is very unknown. I felt like I needed support from the performers somehow.”

The soft-spoken Yamazaki and the winsome Nishimura, who met 20 years ago in their native Japan, make for an entertaining couple. When asked what he admired about Nishimura’s dancing, Yamazaki, who understands English but speaks mostly in Japanese, paused for several uncomfortably long seconds. Her eyes wide with anticipation, Nishimura, who helped with translation, waited for a response. And waited.

It can take Yamazaki some time to find the right words, but once he does, he gets to the essence. “Her body can easily transform,” he said. “Also, it looks transparent — like light can penetrate it. Sometimes her dancing looks like the wind that blows.”

Nishimura, who truly is a remarkable dancer — and one who performed with the pop artist Sia — smiled. He passed the test. These are edited excerpts from a recent conversation with them.

Yamazaki: It makes you think of nature.

Nishimura: It’s very still, but things are happening. One day, we went to the park after rehearsing, and we were all like, “Oh my God, this is what’s happening in the piece.”

Yamazaki: Half of the floor is covered by aluminum sheets. That also helps to make an unreal atmosphere. Thomas Dunn, the lighting designer, is a magician.

Nishimura: He has strong ideas to use really bright reflecting light. The dancers will almost go blind. There is no landmark you can hold onto. Also, we are creating the universe as one group. And it’s not like we are looking at each other, so we have to heighten our listening skills.

Yamazaki: When Thomas saw a rehearsal, he said, “If someone’s ego pops up, this world may crash.” In this piece, every element coexists. I like that.

Nishimura: When Kota keeps watching the still world, he also has a desire to break it.

Yamazaki: I am still in the process of breaking it. If I wanted to make something vaporize or evaporate, I think it’s necessary to boil it before that vaporizing happens.

Yamazaki: I’m thinking about an image. (Laughs)

Did you watch “Lost”? I watched only the last-last episode, and in “Lost,” all the characters were supposed to be dead, but in the very final episode, they meet at church in this very bright light. In my imagination, people kind of vaporize in the very bright light, like a mirage. They become a mirage.

Yamazaki: When you’re running, it’s never the same, even though it looks like right-left, right-left. Running is ever evolving, ever changing — you are going through landscapes and weather. Everything is different all the time, which is very connected to my vision for dance.

Nishimura: Kota almost exaggerates that difference. He does different steps while running. Sometimes his way of running looks like dancing a little bit. Kids or dogs kind of chase after Kota.

Nishimura: When I was in college, I was a member of a kind of dance club in Japan, and the coach of the club was one of Kota’s dancers, so I went to see him perform. We were friends for quite a long time.

Nishimura: We started dating 17 years ago. Kota was older — like my dad’s age almost. Also, I thought Kota was gay.

Copyright 2024 New York Times News Service. All rights reserved.