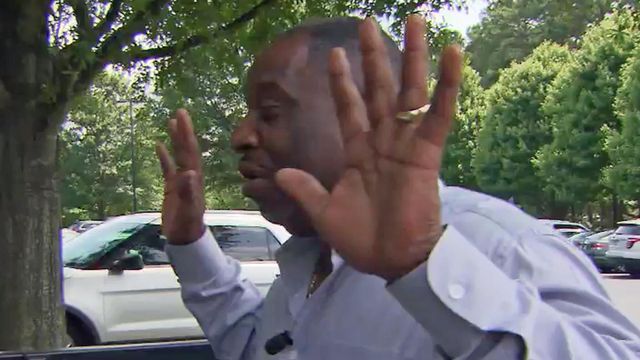

'I was terrified': Raleigh man says he became traffic-stop statistic

In some North Carolina cities, black men are two to three times more likely to be searched by police, according to state traffic stop statistics. For Raleigh resident John Hunt, those numbers became all too real last month on the shoulder of U.S. Highway 1 in Vance County.

Posted — UpdatedHunt was heading home to Raleigh when a Vance County sheriff’s deputy got behind him. Hunt says he didn't want to stop over the crest of a hill, so he turned on his flashers until he found a safer place to pull over. He says he was shocked when the deputy ordered him out of the truck, gun drawn.

“I thought he was going to shoot me,” Hunt said. “He had the gun on me the whole while and got behind the truck, instructed me to bend down on my knees. And when he did that, another officer, he took my hands, he snatched it back, and another officer came, turned to the side, pulled a gun on me, and the other officer that stopped me put the handcuffs on me.”

Hunt asked, but said he wasn't given a reason for the stop. Deputies didn't ask as they searched his truck, he said. “I was afraid. I was terrified."

On that roadside, Hunt became part of a troubling statistic.

“Unfortunately, I'd have to say I'm not shocked (about Hunt’s story),” Baumgartner said. “We always like to think we're living in a society where these kinds of disparities are lessening, but we're not. Actually, they're getting worse.”

He says he fears “the young men in the community are acting out more because they've become increasingly accustomed to being disrespected, and the officers are being increasingly aggressive because they're involved in a dynamic that's a downward spiral.”

Baumgartner is encouraged that communities like Durham and Fayetteville are responding to racial concerns with changes, such as written consent and added sensitivity training for officers.

“It's going to continue to be unpleasant, but we can't solve a problem if we don't have those difficult conversations,” he said.

As for Hunt, he says he knows “all officers are not like that. It’s just a small percentage that are like that.”

Deputies eventually let Hunt go with no charges, but the experience changed his outlook.

“I can see why people would run if someone (is) pulling a gun on you, because you're afraid … even if you haven't done anything wrong,” he said.

WRAL Investigates repeatedly asked the Vance County Sheriff's Department to comment about Hunt's stop, as well whether an internal investigation was conducted, but did not receive a response. Durham and Fayetteville police also declined to comment on their high rates of searching black drivers.

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.