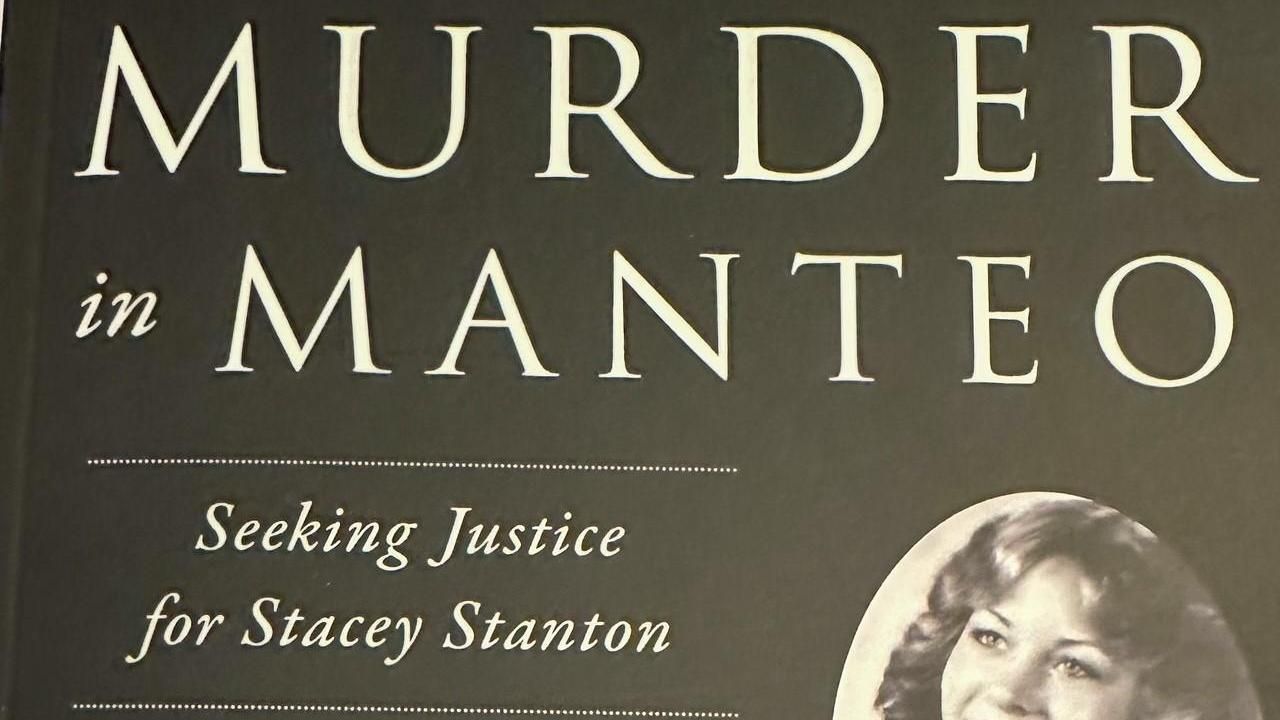

JOHN RAILEY: Murder in Manteo - seeking justice for Stacey Stanton

EDITOR'S NOTE: This is the first of two parts -- excerpts from John Railey's forthcoming book "Murder in Manteo; Seeking Justice for Stacey Stanton." Railey is a North Carolina journalist and author of two previous books the Outer Banks: "The Lost Colony Murder on the Outer Banks: Seeking Justice for Brenda Joyce Holland" and "Andy Griffith’s Manteo: His Real Mayberry."

From the Author’s Note

For decades, young women have been coming in growing numbers to the Outer Banks to work. One of them, Elizabeth Stacey Stanton, 28, a beloved resident of Manteo, was found dead in her downtown apartment on the Saturday afternoon of Feb. 3, 1990. Her neck, right breast and vagina had been brutally slashed, the most horrendous crime in the town since 1967. A rushed investigation, with the tourist season coming on and the Manteo police chief tangling with his governing board, culminated in a rushed charge and conviction.

The questions about Stacey’s case linger to this day. Two determined appellate lawyers, one, Edgar Barnes who risked his burgeoning law practice in Manteo and later another, Chris Mumma, who had given up her lucrative corporate career to fight for criminal justice in general, sought to answer those questions. Stacey could have been their sister or daughter, a realization that never left the lawyers as they worked the case, having to study her crime scene photos that would forever haunt them. Stacey had waited tables in Manteo, charming her patrons with big smiles that belied growing trouble she was experiencing.

Even on a tiny island there are people we think we know but really do not. In writing this book, each interview peeled away another layer toward uncovering the hidden truth, often tied to the complexities of race: Stacey was white, and a main suspect was Black. It might be easy to dismiss the wrongdoings that will unroll here as something from another era. But the same problems persist to this day nationwide: investigators and prosecutors rushing to make murder charges, leaving the real killers free, endangering the public.

From Chapter Two: Where’s Stacey?

Manteo, February 1990 -- There was a magic to Roanoke Island, with “The Lost Colony” outdoor play having four decades before birthed the career of Andy Griffith, who had worked his way up to playing Sir Walter Raleigh in the play. Now Andy lived in a fine house on the North End of the island. The year before, 1989, he had filmed a double episode of his latest show, Matlock, on the island, his way of giving business back to his island.

Stacey worked at the Duchess of Dare diner in downtown Manteo and her after-work hangout, the Green Dolphin bar, was nearby. Many of the bar regulars spoke in the Outer Banks brogue, riffing on the Old English of their ancestors -- tide pronounced “toide” and ice pronounced “oice.” Politicians stopped by as well, including Marc Basnight of Manteo, on his way to becoming the most powerful leader of the state Senate in modern history, charming the Raleigh crowd with his beautiful brogue as he waltzed around them in getting his bills transformed into legislation, millions of dollars in pork-barrel money flowing into Outer Banks projects. Andy, close friends with Basnight and one of his earliest and best supporters, had filmed one of the Matlock scenes in the Green Dolphin.

Stacey had always shown up for work on time at the diner. When she didn’t make her 2:00 p.m. shift on Saturday, February 3, 1990, her co-workers worried. Terri Williams, a Dare County deputy sheriff who moonlighted by hostessing at the restaurant, eventually went in the apartment and found Stacey lying on her back in her living room. Williams felt Stacey’s wrist and could not get a pulse. Stacey was dead. The investigation into her slaying was about to begin.

Deputy Williams, who worked the civil side of law enforcement, serving papers, went by the apartment later that afternoon, finding it “a zoo,” with civilian gawkers walking in and out among the lawmen, going against all she’d learned about securing crime scenes.

Capitol Broadcasting Company's Opinion Section seeks a broad range of comments and letters to the editor. Our Comments beside each opinion column offer the opportunity to engage in a dialogue about this article. In addition, we invite you to write a letter to the editor about this or any other opinion articles. Here are some tips on submissions >> SUBMIT A LETTER TO THE EDITOR