Data on non-citizen voters offers questions, not answers

Despite claims, national polling data provides little evidence that non-citizens are casting ballots.

Posted — UpdatedThe goal of drawing a sample is to have this smaller group of people look exactly like the larger population they are meant to represent. Non-citizens who think it is worthwhile to take surveys about U.S. politics, though, are likely more politically active and attentive than their counterparts who are not part of the study. Rather than recruiting respondents via probability methods – in which each person had an equal chance of being asked to be a participant in the study – the CCES allows respondents to opt-in at their own discretion.

This method is problematic for the same reasons that surveys on web pages do not generate valid results without adjusting for known population parameters such as age, gender, education, etc.

It is likely that many non-citizens who are registered to vote in their home country, but not in the U.S., answered yes. Indeed, of the 75 non-citizens in the 2008 survey who said they were registered to vote, 15 were verified as not being registered at all. Another 46 could not be matched to actual voter rolls and verified one way or another. As a result, only 14 of the 75 could be verified as registered.

Third, these claims about voting by non-citizens are being made based on incredibly small absolute sample sizes. In 2010, for example, just 13 out of 55,400 respondents claimed to be non-citizens and voted. I think it is a mistake to heed claims based on unrepresentative samples whose sizes are equivalent to rounding errors. To be sure, some non-citizens have surely voted, but these data are ill suited for confidently estimating the exact percentage who do.

In terms of policy implications of illegal voting by non-citizens, two things I've read stand out.

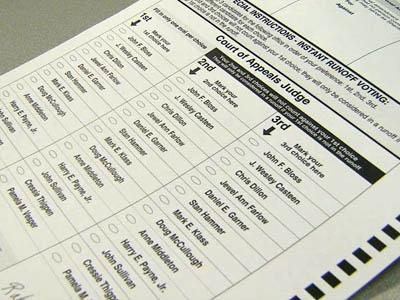

One, as the second Monkey Cage post suggested, it is easier to make sure votes of non-citizens don’t affect election outcomes by making it easier for actual citizens to vote. If so, illegal votes would be an even smaller share of the total vote and have less of a statistical ability to tip the balance of an election. Second, instead of requiring voters to produce state identification that doesn't preclude being a non-citizen, a superior requirement would be mandating a national identity based on verified citizenship status. Political realities, however, make the latter option unlikely, and recent laws in many states arguably make it more difficult, not less, for actual citizens to vote.

Related Topics

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.