Supreme Court justices grapple with NC partisan gerrymandering case

North Carolina's congressional map took center stage at the U.S. Supreme Court Tuesday in a partisan gerrymandering case that could have broad implications for state legislators who draw district lines across the country.

Posted — UpdatedIt was the first of two separate but closely linked cases justices heard Tuesday centering on challenges to Republican-drawn maps in North Carolina and Democrat-drawn maps in Maryland.

In North Carolina, maps drawn by Republican legislators were originally invalidated by a federal court in February 2016 over allegations of racial gerrymandering. State lawmakers tried again that year, swapping out racial demographic data for election results.

This explicit goal of maintaining "partisan advantage," Rep. David Lewis, R-Harnett, said at the time, was a legal and reasonable alternative in the face of the court's ruling. And he said so during debate over the new maps in 2016.

“I propose that we draw the maps to give a partisan advantage to 10 Republicans and three Democrats, because I do not believe it’s possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and two Democrats,” Lewis said.

That political calculus – Common Cause, the North Carolina Democratic Party and the League of Women Voters argued in a lawsuit over the maps – constituted an illegal partisan gerrymander.

A federal court agreed, declaring the new maps were still unconstitutional. An appeal by Republican lawmakers elevated the issue from North Carolina to the high court as Common Cause v. Rucho.

At issue in the North Carolina case is whether, as plaintiffs claim, mapmakers violated the First Amendment and Equal Protection rights of voters and whether, by designing the outcome of elections – explicitly drawing a map to elect 10 Republicans and three Democrats – they violated the Elections Clause.

The Maryland case – Lamone v. Benisek – accuses Democratic mapmakers of diluting the votes of Republicans, violating their First Amendment rights and effectively penalizing them for their voting histories.

Decisions aren't expected for several months.

A 'political thicket'

The last time the high court took up partisan gerrymandering was just last year, when a case out of Wisconsin raised advocates' hopes that justices would act to end the practice. But issues of whether plaintiffs had the legal ability to sue over the alleged gerrymandering prompted justices to send the case back to a lower court, stalling the pending North Carolina case in the process.

But unlike the Wisconsin case, Gill v. Whitford, the justices Tuesday posed no questions to either side about standing.

Instead, they focused largely on what manageable standard, if any, courts might use if they were to decide which maps would pass constitutional muster.

Such a ruling, attorney Paul Clement argued on behalf of North Carolina lawmakers, would trigger a flood of cases that would put the court in a position to decide elections.

"Once you get into the political thicket, you will not get out," Clement said. "You will tarnish the image of this court for the other cases where it needs that reputation for independence so people can understand the fundamental difference between judging and all other politics."

To that claim, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg explicitly objected.

"Exactly what you said – just what you said now – that was the exact same argument about don't go to one person-one vote: The courts are going to be flooded with cases and they'll never be able to get out of it," Ginsburg said. "That's not what happened."

Clement countered that an argument that didn't work in one context may work well in another. Legislators, he said, can deal with one person-one vote. But taking partisanship out of the redistricting process means "you're really either telling them to get out of the business of redistricting entirely or you're opening yourself up for case after case after case."

That's the primary problem even liberal Justice Stephen Breyer noted in his comments to attorney Emmet Bondurant, arguing for Common Cause.

"There is a great concern that, unless you have a very clear standard, you will turn many, many elections in the United States over to the judges," Breyer said. "There's always someone who wants to contest it."

Toward a new standard?

Members of the high court have long expressed a hesitation to weigh in on redistricting, which, by Constitutional mandate, is the domain of state legislatures.

Yet, justices have often acted to curb lawmakers of their worst abuses.

Decades of lawsuits over racial gerrymandering, for example, resulted in clear standards courts use to assess compliance with the Voting Rights Act, determining whether newly drawn maps disenfranchise minority voters.

No such standards exist for partisan gerrymandering.

But plaintiffs argue establishing manageable standards is possible and appropriate for the court, bolstered by a 2004 opinion from Justice Anthony Kennedy. He warned the court that closing the door to such standards ever emerging might show justices "prematurely abandoned the field."

Plaintiffs in the case argue their measures meet Kennedy's hypothetical manageable standards. That's despite the swing vote's notable absence from the bench: He retired in 2018, just weeks after he joined a unanimous decision to send Gill back to the lower court.

In the courtroom Tuesday, many of the justices' questions to attorneys for Common Cause and the League of Women Voters focused on whether their standards for evaluating district maps boiled down to deviations from proportional representation.

Under Republican-drawn maps in North Carolina, the GOP secured 10 of the 13 seats in the state's congressional delegation in the last two elections. That's despite receiving about 53 percent of the state's popular vote in 2016 and just over half the popular vote in 2018.

But as Chief Justice John Roberts has pointed out in prior cases, ours is not a system of proportional representation. Justices need a better way to tell whether maps are out of whack enough to overturn them by court action.

Bondurant acknowledged the legislature has wide discretion to draw district lines even with some partisan influence. But they cross the line, he said, when they dictate electoral outcomes or favor a class of candidates.

"That first one – dictate electoral outcomes – I think is going to turn on numbers, right? How much deviation from proportional representation is enough to dictate an outcome?" Justice Neil Gorsuch said. "So, aren't we just back in the business of deciding what degree of tolerance we're willing to put up with from proportional representation?"

The closer the outcome is to proportional representation, Bondurant responded, the harder it would be to argue intentional discrimination.

But for the North Carolina case, he said, that intent was clear. A ruling from the court that the legislature "can't put its thumb on the scale and pick winners and losers" would be easy to understand.

"That is a standard that legislators will obey," Bondurant said, "and that is a standard that will reduce, not increase, litigation."

'Limited and precise'

In her arguments to the court on behalf of the League of Women Voters, attorney Allison Riggs said failing to act would back up the legislature's belief that the court would "implicitly endorse unfettered partisan manipulation in redistricting by declining to rein in this most egregious example."

She also proposed a three-part "vote dilution test" courts could use to screen partisan gerrymandering cases before deciding on their merits in an effort to avoid being inundated by lawsuits.

Plaintiffs would first have to prove specific partisan intent, then a "severe and durable effect" on the losing party. Lastly, the court would examine whether there's any other reason for the dilution of votes – like the effects of geography or other neutral criteria.

The result, Riggs said, was a "limited and precise" test that could be used by the lower courts to evaluate cases.

Several of the conservative justices, though, worried that the baseline for such a test would still be proportional representation.

Not so, Riggs responded, pointing to research by Duke University mathematics professor Jonathan Mattingly that generated 20,000 possible North Carolina congressional maps that satisfied the legislature's neutral redistricting criteria. That analysis showed that only about 1 percent ended in a congressional delegation with 10 Republicans and three Democrats.

"If what we're left with is no extreme statistical outlier or no grossly asymmetrical map, the legislature can choose from any of those plans," Riggs said.

On the steps

Outside the packed courtroom – which included state House Speaker Tim Moore and former state Sen. Bob Rucho among the audience – Republican Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan told a crowd of reporters and Capitol onlookers that gerrymandering was "one of the biggest problems in America today."

He was joined by fellow Republican and former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, who called the practice a "national scandal" and a "disservice to the people."

Minutes earlier inside the court, justices asked attorneys whether gerrymandering was a problem that would soon solve itself, especially in light of citizen referenda in several states redesigning the redistricting process.

"There will be no self-healing," Schwarzenegger told the crowd, arguing that North Carolina and Maryland should adopt independent redistricting commissions like his own state of California.

There's a bill stuck in the current session of the North Carolina legislature aiming to do just that. Moore, R-Cleveland, said he wasn't in favor of it.

"The voters, if they are happy or unhappy, they can keep us or fire us every two years," Moore said. "With an independent commission, they’re ultimately not accountable to anyone."

He said he was hopeful for a favorable decision "unless the court ignores years of jurisprudence that a legislative body can take into account partisan lines when it comes to redistricting."

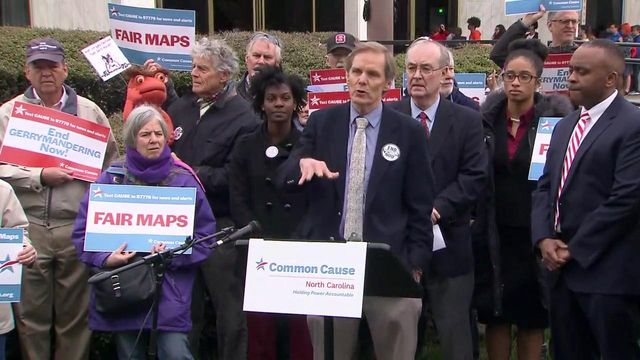

Meanwhile, back in Raleigh, North Carolina Common Cause Executive Director Bob Phillips noted that Tuesday was the 207th anniversary of when the term "gerrymander" was coined by a Boston newspaper. He called for lawmakers to debate the independent redistricting proposal, noting that Moore supported the idea before Republicans gained the legislative majority in 2010.

"Anything, almost, would be better than what we do now," Phillips said at a news conference outside the Legislative Building. "Redistricting debate is good for the state. It's good for both parties."

Rucho, whose name sits atop a case with the potential to change how lawmakers across the country draw political maps just in time for the decennial U.S. census, said he still believes the map he and his colleagues drew was the right one.

"They accused us of following the law too hard," Rucho said. "How do you follow the law too hard?"

Related Topics

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.