'We're asking for accountability.' Wake leaders, AG Stein pitch their social media solutions to parents, students

Social media companies need to make their products less addictive and North Carolina and Wake County leaders need to do more to help teens with their mental health, leaders said Monday.

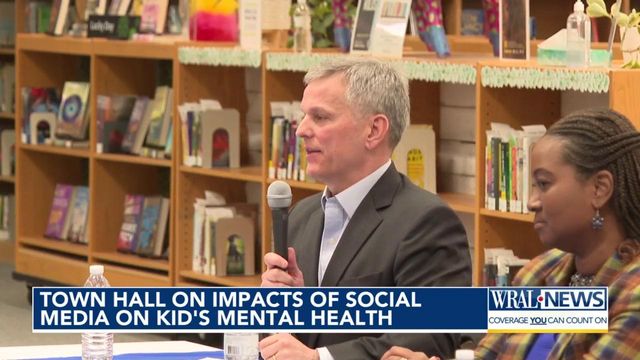

Wake County leaders and North Carolina Attorney General Josh Stein met with dozens of elected officials, parents, students and other community members during a town hall on social media Monday.

The North Carolina Department of Justice hosted the town hall Monday at Athens Drive Magnet High School in Raleigh, with Stein, Wake County Board of Education Chairman Chris Heagarty, Wake County school board member Cheryl Caulfield and Wake County Commissioners Chair Shinica Thomas. It lasted just one hour, with many audience members still hungry to ask the leaders questions afterward, something Stein said “underscores the urgency of this topic.”

Concerns among leaders and audience members didn’t differ much. Discussion around solving problems believed to be connected to social media drew mixed responses, and some questioned how effective the government could be in regulating the companies. Leaders themselves listed a wide variety of deficiencies — such as limited mental health care providers and limited school resources — that hinder their ability to respond but pushed the idea that social media companies themselves can play a major role in improving the social media experience.

“What we're asking for now is accountability,” Caulfield said. “Where we can actually have the control, as a parent and at a school level.”

The town hall was the latest in a series Stein, now the Democratic nominee for governor, has hosted on social media across North Carolina in the past few months.

Stein and attorneys general from 32 other states sued Meta — the parent company of Facebook and Instagram — in October. They alleged the company ensnared kids in an additive platform and deceived users about the safety of social media platforms.

"It's not about taking social media away from young people because they use it,” Stein said Monday. “It's about having limitations put on by social media companies to better protect kids."

In February, the Wake County Board of Education voted to join a lawsuit against Meta, ByteDance, Snap and Google. Lawsuits from Wake and about 200 other school boards argue that schools have had to handle the fallout of psychological damage caused by their apps.

In a statement to WRAL News on Monday, a Meta spokesman said the company had developed tools to help parents set time limits on their apps, and verify age, which blocks users from sending direct messages to teens under 16 who don’t follow them and sending notifications to teens under 16 to take social media breaks.

“These are complex issues but we will continue working with experts and listening to parents to develop new tools, features and policies that are effective and meet the needs of teens and their families,” the company’s statement said.

North Carolina children are spending hours on social media every day, encountering a mix of content about their friends or interests. But much of that content can turn dark, and fast.

“We have been wrestling with a number of problems in our school systems that are all directly tied to social media,” Board Chairman Chris Heagarty said. “We've been seeing this problem compound for years.”

Heagarty gave an exhaustive list of recent events and referenced the November fatal stabbing of a student at Southeast Raleigh Magnet High School, which was preceded by a fight and students crowded around, filming it. He touched on issues that have popped up in schools across the country, such as cyberbullying, bomb threats and social media challenges encouraging students to break things.

“In a very recent time period, we've seen horribly racist social media comments posted on bogus sites connected to Broughton High School,” Heagarty said. “We have seen social media accounts set up for Leesville Road fights, to glamorize violence of students against other students humiliating them… We have seen a culture develop where our law enforcement officers and our teachers cannot intervene in situations where students' lives are at stake, because they can't get through rings of students all gathered around with their cameras, trying to record these incidents of violence — glamorizing, promoting it. And this has to change.”

Heagarty and others also noted fewer public examples of social media harm, including algorithms that feed negative content to people on topics like self-harm, suicide, eating disorders and drug use.

Leaders, including Stein, floated the idea of not allowing students to have access to their phones during the school day.

Several counties in North Carolina have already done that, He said feedback in those counties so far is students are paying more attention in class and the students aren’t too bothered by not having their phones because they’re not missing anything happening online if their peers don’t have access to their phones, either.

Taking away cell phones during the school day could help some students academically, said James Cochran, an Athens Drive freshman. But it wouldn’t resolve teens’ problems with social media use, because they can also access social media at night, on the weekends and all summer long.

“School is only so many hours,” James said.

Athens Drive junior Liz Tomblin said social media use is here to stay.

“To tell teens not to use social media is extremely unrealistic,” Tomblin said.

But mental health challenges are real, she said, and they’re not being addressed in schools.

“So what is the plan for addressing mental illness in schools, because I don’t see much of it in school now?” she asked.

The question prompted leaders’ admissions that North Carolina isn’t doing enough.

“We are not doing a good job as a state,” Stein said. “We are not prioritizing mental health for young people.”

He said expanding Medicaid eligibility to more people — and the one-time federal incentive money for doing so — will help some but not enough.

“Because of that there’s going to be substantially more mental health providers because now people have a way of getting paid,” Stein said.

Heagarty said the number of providers is a problem because school officials might talk to parents and refer a child for mental health services, but then no agency can actually take them.

“The local providers are not accepting new patients,” Heagarty said. “They just don’t have the capacity.”

The school system needs more state and local-funded social workers and other support professionals but can’t even hire for the ones it has.

“Because we can’t find mental health professionals, social workers or others to fill these jobs, based on the pay and then just based on the workforce right now,” Heagarty said.

The school system needs to educate parents on what services are out there, Caulfield said.

The work can’t be left to schools or just one agency, she said, adding a child’s issues can start at home or in their neighborhood can become a problem at school, she said, and problems at school don’t stay at school.

More groups need to work together more, she said.

“It’s really a whole community effort,” she said.

.