The language evolves, but facts are necessary to convince people not to experiment with drugs

Students at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill now have access to free kits that revive someone suffering an opioid overdose and test strips to see what the drugs they are about to take contain.

These steps, which assume students are using drugs, are designed to save lives, but prompt the question: Will the tactics work for today’s students?

Riley Sullivan, the group’s cofounder and director, believes the kits will actually help reduce drug use on campus. He said the group has handed out about 900 naloxone kits and 500 fentanyl test strips this semester alone.

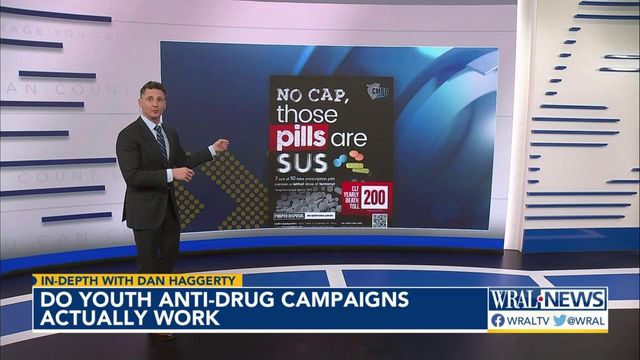

In Charlotte, a public awareness campaign called “Street Pills Kill” uses the slang of youth to convey the same message. The phrases are the new generation of “just say no” or “above the influence.”

“No cap, those pills are sus.”

Young people use the words “no cap” to say they are telling the truth or they aren’t lying. To use the word “cap” would mean someone is lying.

“Sus” is short for suspicious.

Another sign says: “you plus street pills equals … we don’t ship.”

"Ship" means you want two people to date or enter a romantic relationship.

The language is how kids speak nowadays, but will they listen to the kind of messaging?

Remember McGruff the Crime Dog or the “this is your brain on drugs” ad of a man cracking an egg on a skillet?

You might also remember other campaigns like "truth"and "DARE" to name a few.

Do media campaigns actually keep kids away from drugs?

Several studies show they aren’t effective.

A 2008 study published in the American Journal of Public Health found, "The campaign is unlikely to have had favorable effects on youths and may have delayed unfavorable effects."

A 2014 analysis from the Cochrane Library looked at 19 different studies.

Eight studies found ads had no effect on drug use. The others had mixed results. However, the researchers concluded, "caution is needed in disseminating mass-media campaigns tackling drug use.” It means they could do more harm than good.

Some parents may feel like they can share their stories and experiences with their kids to teach them.

A 2013 study published in the journal "Human Communication Research" found, "Even when there is a learning lesson, such messages may have unintended consequences for early adolescent children.”

It also found, "children whose parents did not disclose drug use ... but delivered a strong anti-drug message ... were more likely to exhibit anti-drug attitudes."

Knowing what their parents did could make kids more curious than cautious when it comes to drug use.

The same goes for heavy-handed messages like “say no" and “don’t do drugs." Without clear facts, they can have the opposite effect.

Teenagers may not have a medical degree, but they’re not dumb.

A 2013 article in Popular Science put it this way, "The ads can draw attention to a gap in what the viewer knows about drugs, making them more curious ... the ads bring up the implicit question .... should I do drugs?"

Research shows bridging that gap with facts is the best practice.

"Above the Influence" is a good example of this.

Their ads mostly show what teens could be doing instead of doing drugs — showing a kid who's missing out on fun with friends because he's too busy being lazy and stoned.

A 2011 study in Prevention Science found that this campaign could be connected to reduced marijuana use.

The "truth" campaign had similar results. Their ads show the often brutal realities of smoking, including how hard it is to quit and the medical conditions that can come after.

A 2009 study in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine found this campaign was a viable strategy to prevent youth smoking.

Stanford University is rolling out a program just like this called "Safety First”. They still tell kids not to use drugs, but then go a step further. They give scientific explanations about how weed is different from cocaine is different from tobacco is different from alcohol.

The program explains how withdrawals work and what a brain actually does when someone uses drugs.

They talk about how to recognize the difference between use and abuse, and how to respond in an emergency.

Charlotte’s “Street Pills Kill” campaign has lessons for parents, drug disposal locations and explains how fentanyl works.

Fentanyl can be mixed into almost any drug or substance. The campaign also explains how to use Narcan, the nose spray that can save a life from an overdose.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg police are also working to get Narcan into schools.

Schools in Wake, Franklin, Person, Johnston and Cumberland counties all have school resource officers that carry Narcan.

The Carolina Harm Reduction Union said while they’re handing out test strips that can detect fentanyl, they’re not endorsing drug use, but saving lives.

Either way: It’s clear people need to take action.

Last year, an estimated 4,243 people died from an overdose in North Carolina. At least 300 of them were 24 or younger.

According to the research, education presented in the right way can actually bring those numbers down — no cap.