Spotting $62 Million in Alleged PPP Fraud Was the Easy Part

The criminal complaints read like catalogs of luxury bling: a diamond-laden $52,000 Rolex, a gambling spree at the Bellagio, two Lamborghinis, a pair of Cadillac Escalades, a Rolls-Royce. All that and more, law enforcement officials said, was financed through schemes to defraud the federal government’s signature coronavirus relief program for small businesses.

The Justice Department has made at least 41 criminal complaints in federal court against nearly 60 people, who collectively took $62 million from the Paycheck Protection Program by using what law enforcement officials said were forged documents, stolen identities and false certifications.

They are just “the smallest, tiniest piece of the tip of the iceberg,” said Hannibal Ware, inspector general of the Small Business Administration, which led the program.

But with their ostentatious spending and clearly faked records, those examples have also been the easiest to spot.

The Paycheck Protection Program, a centerpiece of the coronavirus relief bill, poured $525 billion into the economy in just four months before coming to an end. More than 5 million businesses received loans, which could be forgiven if used for payroll and certain other expenses. Now, that hastily created and frequently chaotic program is entering its next messy stage, one that lenders and government officials expect to take years: the hunt to recapture illicitly obtained cash.

The challenge facing scores of state and federal agencies is enormous. The Small Business Administration’s fraud hotline, which received fewer than 800 calls last year, has already had 42,000 reports about coronavirus-linked graft.

But many of the cases investigators ultimately pursue will not have telltale clues like expensive watches and Italian sports cars bought by people who said their small businesses were in need of immediate help. Future cases will be more thorny, involving owners who tried to exploit gray areas in the program’s rules or the desperation of their employees.

Several workers told The New York Times that their employers had asked them to repay a portion of their earnings or work for free in the future. That type of arrangement wasn’t allowed under the program’s rules.

Under the initial rules, borrowers who wanted the loans forgiven had to spend most of the money within eight weeks. Those limits frustrated many owners, and some appear to have tried to quietly break the rules, according to the workers, who asked not to be identified to protect their livelihoods.

The owners of a Pilates studio in Manhattan told employees that some instructors — who have been running virtual classes since the city shut down gyms — would be paid extra for a few weeks out of the studio’s loan but that their wages would be garnished after in-person classes resumed. Two instructors shared emails with the Times describing the plan, including an all-staff note from the owners that described the payments as “an advance on future work.”

An employee at a speech therapy clinic in Minnesota described how the owner told employees in May that she would use the clinic’s loan to pay them for a 40-hour week — but that if they didn’t have enough client bookings or other projects to fill the time, she would expect them to repay those hours with uncompensated labor later in the year. The boss backed down, the employee said, after the employee consulted a lawyer and told the boss that the plan appeared to be illegal.

And a worker at a dermatology clinic in North Carolina said her boss had used a paycheck program loan to increase the worker’s monthly pay to $7,200 in May — more than she usually made — but then, without warning, began garnishing the worker’s pay the next month. In July, she was asked to sign a document (which she shared with the Times) retroactively agreeing that the money she received had been a loan. To keep her job, she agreed to pay back $250 a month out of her earnings.

Those are among the “more complicated schemes at play,” said Ware, the inspector general. “We do know that that’s happening,” he said. He declined to discuss it in detail to avoid imperiling active investigations.

One reason those investigations will be more complicated: Congress relaxed some of the rules partway through the program, effectively penalizing borrowers who used up the money quickly to comply with the original rules.

The relief program was intended to quickly disburse billions of dollars in loans of up to $10 million. Virtually every small business in the country qualified, but the government deliberately eliminated many of the hurdles that normally accompany business loans, like a thorough lender verification of the applicant’s tax records and payroll documentation. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin pushed banks to approve and fund loans in as little as a day. That made the program an irresistible target for thieves.

“Any time you have large amounts of federal aid available, it’s going to bring out all the bad guys,” said Kathryn Petralia, a co-founder and the president of Kabbage, an online lender that handled 297,000 loans for the program.

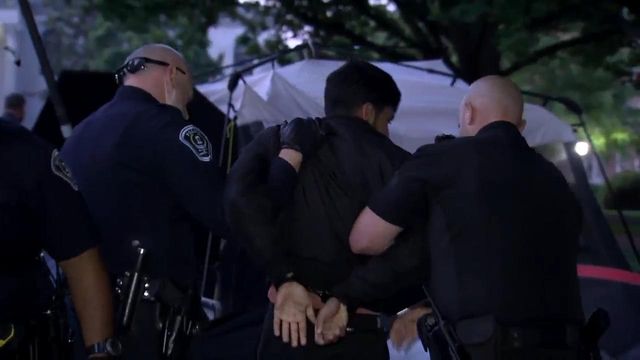

The arrests started just weeks after the program began in April.

In one case, a Texas man with convictions for forgery and robbery sought loans from six lenders using shell companies with no employees and, in one application, the stolen identity of a wine shop owner who died in April. He collected $1.6 million and spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on booze, nightclubs, a Rolex and a 2019 Lamborghini Urus, according to the complaint filed against him in federal court in Houston.

Other plots were more complex. In the largest criminal case so far, nine people in Florida and Ohio are accused of paying kickbacks to recruit participants in what was essentially an assembly line for fraud. At one house, investigators said, they found stacks of loan paperwork for more than 80 businesses, filled with forged documents and false claims about the size of the businesses’ payrolls. Banks rejected many of the applications, according to court documents, but at least 42 were successful, netting the defendants more than $17 million from the program.

Lenders said the flurry of indictments was a sign that oversight was working. “The fact that a loan was funded and money was transferred did not necessarily end the scrutiny on that loan,” said David Patti, a spokesman for Customers Bank, which made $5 billion in loans for the program. “There are plenty of investigations going on with many lenders.” In addition to investigations of misused money, lawyers and lenders said, there will be investigations into companies taking loans they didn’t need — a murky area.

In its formal guidance, the Treasury Department said borrowers must be able to show that they could not get access to other loans or cash sources in a way that was “not significantly detrimental to the business.”

“It’s a really gray standard,” said Tyler Woods, a lawyer in Irvine, California, who has worked with corporate clients on their Paycheck Protection Program loans. He called that line “the big kicker that I think will get a lot of people out of jail.”

A Treasury spokeswoman said the Small Business Administration had 90 days to review forgiveness applications after they were submitted and would make sure that borrowers had complied with all of the program’s rules.

While all of the loans are subject to review, only those over $2 million will face a mandatory audit. Those are about 29,000 loans — a heavy demand to place on the already overwhelmed agency. The Small Business Administration did not respond to repeated requests about its audit plans. Ware said his office, which operates independently from the Small Business Administration, was hiring additional data analysts, auditors and investigators as it braced for an extensive oversight effort.

“It’s going to take years,” Ware said of the government’s investigative work. “This will be taking up a lot of our time for the foreseeable future.”