Rose, Ned, Nancy: The lost names and stories of Raleigh's enslaved community

There's so much we don't know about the community of enslaved workers who helped build the earliest foundations of Raleigh. Records are often sparse. Likely thousands of names and faces have faded from history, their stories never recorded.

To accurately tell the history of Raleigh, we need to talk about the people who built it – both enslaved and free.

The Joel Lane house, the onetime center of one of several Raleigh-area plantations that used enslaved labor, has honored the names and memories of the enslaved community that lived and toiled there. Joel Lane is commonly referred to as the "father of Raleigh."

Their names have been cast into a bronze plaque, which will stand as a permanent fixture in the garden after a ceremonial unveiling that is open to the public.

Old Ned. Flora. Old Rose. Suzanna. Hercules. Lunsford. Hasty. Montford.

These are just a few of the names that shouldn't be forgotten, and each one comes with a story.

The names and stories of the enslaved community

"In the 1760s, before the house was even built, we begin to find records of Joel Lane purchasing enslaved people. We first see reference of Flora in 1763, then Young Sam, Dick, Jack and Stanter in 1765," said Lanie Hubbard, Director of Joel Lane Museum House. "These are people he [Joel Lane] purchased."

The Lane house itself was built in 1769, decades before the city of Raleigh was founded. This rural backcountry community was a collection of plantations, farms, taverns and mills. When Wake County was established in 1771, through legislation introduced by Joel Lane, the county seat was established here, and the people began referring to the area as "Wake Courthouse."

Hubbard said researchers pieced together the names and stories of the enslaved community from documents left behind from the Lane plantation, such as Joel Lane's will, census documents, rare documents noting purchases and sales, and auction records.

Names nearly erased from history: Suzanna, Becky, Nancy

It took researchers a long time to put together the correct names for some of the enslaved people due to transcription errors in the historic records.

"We had a record of a woman named Getawney in Joel Lane's 1794 will. We only recently discovered that 'Getawney' was the result of a modern misreading of 18th century handwriting, exacerbated by smudged ink. Later records refer to a woman named Nancy," said Hubbard. "We only recently discovered Nancy and Getawney refer to the same person."

Lane's will also listed a named Beckey, which was later transcribed as 'Buckey.'

Winton became 'Winter.'

Suckey is listed other places as Susannah.

It's possible the differences between records are due to nicknames within the community. However, Hubbard said some records are likely just carelessness on the part of the transcriber.

Why bother to write someone's name correctly, when they aren't literate and therefore can't correct you? Such was the level of powerlessness in much of the enslaved community – you couldn't even be certain your name would be properly remembered.

The historians on this project are determined to ensure these names don't vanish from history.

A child inherits a child: Hercules and Uncle Harkless

When Joel Lane's father died, he left a 10-year-old enslaved boy named Hercules to his 9-year-old grandson Henry in his 1773 will.

Hercules grew up alongside Henry, then went with him when he started his own house – which would come to be known as the Mordecai House. In her book Gleanings from Long Ago, Ellen Mordecai, Henry's granddaughter, talks about remembering an enslaved man named Uncle Harkless.

In her memories, he's no longer a 10-year-old boy, but an elderly man. She wrote, "He was fond of children, and they were fond of him."

"We think he's the same person," she Hubbard.

A child vanished without a trace: Flora

According to records, Flora was purchased all alone in 1763.

After that record, this 14-year-old's name never appeared again.

"She could have been sold, and we just don't have the documentation. She could have passed away from any number of diseases or childbirth," said Hubbard. "We just can't say."

Families sold, broken apart: Cate, Young Ned, Davy and Montford

It took five years to settle Lane's estate, and during that time an enslaved woman named Cate had two children – Davy and Montford – who had to be added to the legal documents.

"They were born property of Joel Lane's estate even though he was never alive during their lifetimes," said Hubbard.

The two little boys were sold in auction alongside their mother, purchased by neighbor John Haywood. Haywood also bought Young Ned, who was Cate's brother.

"This portion of the family was kept together through the sale," said Hubbard. "Not everybody was, though. Sam, another sibling of Cate and Young Ned, was inherited by Martha Lane."

Having been separated from one brother, Cate spent five years waiting for an auction that would disrupt her life, not knowing whether she would lose another brother -- or her children.

Buying freedom for himself and his family: Lunsford Lane and 'Young' Ned

Young Ned, who later went by Edward, had a son named Lunsford Lane.

Lunsford grew up enslaved by the Haywood family. However, while enslaved, he earned money to purchase his freedom and spent the next 25 years advocating for abolition.

According to Lunsford, his father Young Ned taught him to mix the unique blend of tobacco which he was allowed to sell under the brand "Edward and Lunsford Lane." He was able to use his earnings to eventually buy his freedom.

Lunsford Lane published his autobiography in 1842, called "The Narrative of Lunsford Lane, Formerly of Raleigh, N.C., Embracing an Account of His Early Life, the Redemption by Purchase of Himself and Family from Slaver, and his Banishment from the Place of His Birth for the Crime of Wearing a Colored Skin."

This enslaved man from the small city of Raleigh in the antebellum South went on to join famous abolitionist Fredrick Douglass on the abolitionist lecture circuit.

"This was a dangerous calling that resulted in his being tarred and feathered and nearly hanged on an 1842 visit to Raleigh to free his family," said Hubbard.

However, Lunsford was ultimately successful, freeing his family – his children, his wife and his father Young Ned.

"He ends his life a free man. But there's so much pain before they reach that happy ending – cruelty and broken families. In this case the family was united, but that was so often not the case," said Hubbard.

The father of Raleigh's role in slavery

Joel Lane died just three years after the City of Raleigh was established. His death caused chaos in the enslaved community on his plantation – the entire community was broken and divided among his children, some of whom were minors.

"In total," said Hubbard, "there were 30-some people enslaved on this plantation. Joel Lane had 12 kids, two wives. We had 15 Lanes total living here, and 43 members of this community enslaved."

"Everything Joel Lane accomplishes, he is able to do in part because of unpaid labor," said Hubbard.

Last February, the memorial with these names was permanently cemented in the gardens of Raleigh's oldest home.

"We wanted to honor them by name as individuals. The people who lived and worked and were held in bondage here," said Hubbard.

Their names are visible, indelible, cast into bronze and mounted on granite to remind future generations of Raleigh there are more stories here than meets the eye, and history is hiding beneath the surface.

Check out more of Raleigh's Hidden History

Discover the secrets hidden beneath 250 years of paint, uncovered at Raleigh's oldest home.

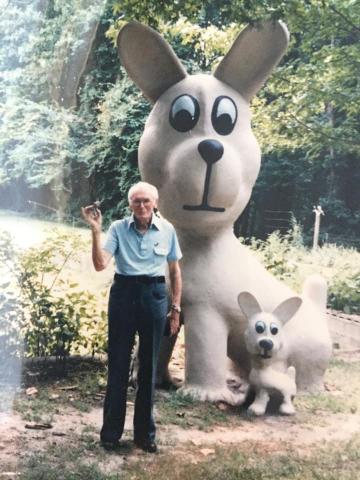

Explore the history of the 12-foot pink dog in downtown Raleigh, the last remaining piece of Gotno Farm -- a strange safari full of giant plaster animals built off Buffaloe Road starting in the 1940s and 50s.

Or travel back to simpler times when the Peanut Man fed pigeons in downtown Raleigh, when Darryl's had a circus room on Hillsborough Street and when Raleigh still had its own baseball stadium.