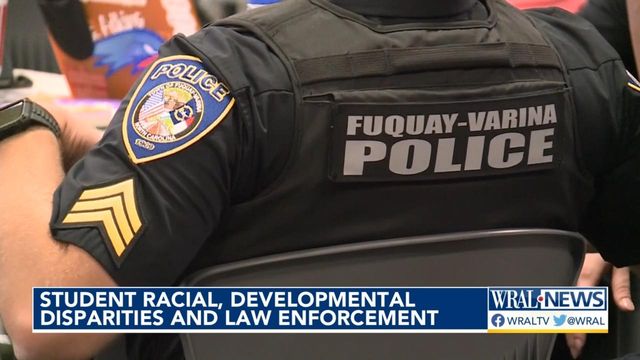

NC students of color and students with disabilities are sent to police 2.5 times as often, ACLU says

North Carolina students of color and students with disabilities are disproportionately referred to law enforcement, raising questions about the impact of school resource officers on campuses, according to a new report from the American Civil Liberties Union.

The number of school resource officers on K-12 campuses is rising, especially with recent multimillion-dollar increases in funding from the state.

Student discipline more broadly — including suspensions and expulsions — has for decades been disproportionately used against students of color and students with disabilities, according to state data. Now, the ACLU argues the increase in officers at schools leads many of those same students to a potentially more severe form of punishment — referral to law enforcement.

During the 2017-18 school year, according to the ACLU, law enforcement officers and school staff referred Black students to law enforcement agencies 2.4 times as often as they referred white students. They referred students with disabilities 2.5 times as often as they referred students without disabilities.

From 2017 through 2023, they filed complaints of disorderly conduct, which can be more minor offenses, against Black students four times more often than against white students.

Disorderly conduct, as applied in North Carolina and beyond, could be refusing to follow orders, cursing in hallways or minor skirmishes between students, said Sarah Hinger, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU’s Racial Justice Program.

“There really is a wide range, and there’s not limitations on what might be characterized as criminally disruptive,” Hinger said.

But many behaviors are better addressed by professionals with more of mental health background, she argues.

“Sometimes children’s behavior requires intervention,” Hinger said. Certain people are better equipped to positively support students than others.

Capt. Leon Godlock, a longtime school resource officer in Rutherford County and an ex-officio member of the North Carolina Association of School Resource Officers, said schools need both officers and more mental health professionals.

Schools largely don’t choose to take away officers once they have them, even if they could replace them with another professional, he said. Parents often support having them.

“They would rather have both officers and mental health professionals," Godlock said.

North Carolina schools are well short of national recommended staffing levels for other support personnel, including counselors, social workers, nurses and psychologists. Those support professionals could help students who are in crisis or who act disruptively, in ways that could be considered disorderly conduct, Hinger said.

“At the same time what we find is that North Carolina schools are heavily policed, to the detriment of students,” Hinger said.

When schools don’t have other professionals, they often use police officers instead.

Godlock said officers often end up playing the role of a counselor for some students.

Police officers aren’t as well trained to handle children in crisis, but they may end up handling them anyway, said Jenice Ramirez, co-director of the Education Justice Alliance, which seeks to improve inequities in schools and replace police officers with counselors.

“We have to look at the fact that when there is a [school resource] officer in the school building, and then there is a child who is having a misbehavior, the first thought is: 'Wait, who's going to deal with that behavior?'" Ramirez said.

Educators looking for someone to handle student behavior often end up turning to officers, she said.

Then, students of color and students with disabilities are referred to the juvenile justice system more often.

But they don’t necessarily misbehave more often, Hinger and others say. Students with disabilities might struggle when their disabilities are not sufficiently addressed at school.

Some research suggests Black students are disciplined more often for more subjective behaviors, like defiance, the ACLU notes.

Many students feel negatively about the school Resource officers they’ve had at their schools.

Vicki Brent, who co-founded the Wake County Black Students Coalition, said she’s heard from friends who have felt harassed or targeted by the officers who wanted to get them in trouble. Some female students felt uncomfortable by the way an officer was acting toward them.

Police don’t signal safety for everyone, Brent said.

“As adults who aren't in high school anymore, the biggest thing is we think police equals safety, so we put them in our school that will make them safe as well,” Brent said. “But we have to remember these are high schoolers. These are people who are going through so much that, for them, police officers just might mean, ‘Did I do something wrong? Am I a criminal? Because why would a police officer be here otherwise?’”

Brent, now a sophomore at Loyola Chicago, thinks people should define what safety is. What threat is most prescient? The threat of the worst-case scenario or the threat students in crises might feel from police?

She said one of the biggest problems with school resource officers is that many don’t know the students well.

The last officer at Brent’s high school didn’t try to get to know students. He had replaced an officer who was very friendly and had initially created a positive impression of school resource officers.

Godlock, who is Black, argues officers can be valuable to schools but acknowledged many officers in the past have been placed in schools who should not be there.

Being a school-resource officer is about building relationships with kids, families and employees, he said. They should know almost everyone’s name. Many do and even support students in other ways, like providing them with snacks or school lunches when they don’t have lunch money. They greet kids when they enter the building or parents and guardians who are outside.

But some officers are in schools just because they think it will be easier than a typical patrol job, he said.

If the students can't name the resource officer at their school, the officer is not doing their job, Godlock said.

“There are some officers that have been placed in schools that should have never have been there,” he said.