NC laws protect voters against most intimidation efforts

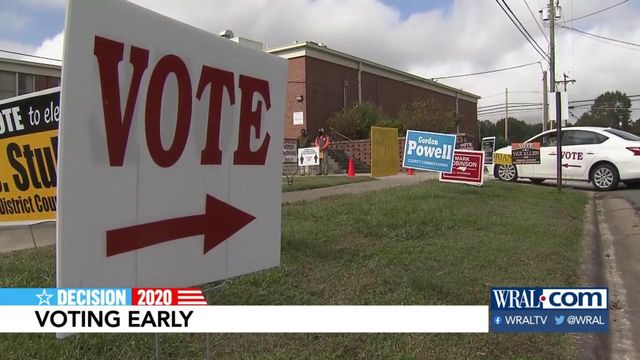

Long lines, confusing rules, malfunctioning equipment: Voters are used to worrying about those. But physical safety? That fear is peculiar to 2020, thanks not only to COVID-19 but to a swelling chorus of speculation about the potential for partisan enforcers at the polls.

President Donald Trump has called on his supporters to join an “army” dedicated to rooting out funny business. For some, that conjured up visions of roving vigilantes with semiautomatic weapons or figures in MAGA hats peering over their shoulders as they voted.

Facebook responded by banning posts that frame election activities in militaristic language. N.C. Attorney General Josh Stein issued a fact sheet filled with reassurances such as “a political candidate’s supporters cannot show up unofficially at polling places to watch voters cast their ballots.”

‘Need to be respectful and polite’

Republican officials, meanwhile, say that — despite a campaign website called armyfortrump.com, which features a call to “enlist” — those who volunteer will do standard political grunt work. Some will serve as the kind of almost invisible onlooker both political parties routinely station at polling places.

“All volunteers and poll watchers receive rigorous training to abide by each state’s laws for observing the voting process,” said Gates McGavick, the North Carolina spokesperson for the Trump Victory campaign.

“We make very clear to volunteers they need to be respectful and polite and are not there to be intimidating.”

Tim Wigginton, a spokesman for the state GOP, struck the same note, saying he would discourage anyone inclined to cause a ruckus near a polling site. “That would be unhelpful,” he said.

Election observers (which is what they’re called, rather than poll watchers) operate under rules set by the legislature and the N.C. State Board of Elections. The party organizations in each party recruit and train them and must provide their names to officials at each precinct several days in advance.

The most lethal thing observers carry is a clipboard. They’re prohibited from speaking to or photographing voters.

If they think something is amiss, they’re to report it to the precinct judge, the county board of elections or officials of whichever party appointed them.

One of their key duties is to receive lists of who has voted, which are relayed to party workers coordinating the get-out-the-vote effort.

With just four days of early voting behind us, it’s too early to conclude that the only thing voters have to fear is fear itself.

Nevertheless, a web search turned up just two reports of incidents at North Carolina polls: An elderly GOP observer (and former state lawmaker) in Wake County shoved a precinct official; and an elderly GOP observer in Guilford County scrutinized Latino voters and took notes.

The only munitions launched thus far have been verbal grenades hurled by Republican lawmakers at the NCSBE. The board drew their fire by suggesting that an overt police presence at polling places might make some nonwhite voters anxious.

Perhaps that’s a touchy subject for the GOP: It was only in 2018 that the Republican National Committee was released from a 1982 court decree that prohibited it from organized activities outside polling places. The ban stemmed from the GOP’s practice in those days of hiring off-duty officers to congregate in uniform near voting sites in Black neighborhoods.

These days, voter intimidation is apt to be less visible but no less effective. Earlier this month, two men were charged with felonies in Michigan for making threatening robocalls to voters in heavily nonwhite precincts, reportedly across several states.

The calls warned falsely that anyone who requested a mail ballot could become a target for debt collectors, police serving warrants or mandatory vaccination campaigns.

Challenges to votes in 2016 'a deceitful operation'

In North Carolina, a report that Trump’s campaign has hired Ryan Terrill to oversee operations at the polls caused heartburn for some veterans of 2016’s gubernatorial dogfight.

That year, then-Gov. Pat McCrory’s campaign, for which Terrill served as political director, challenged hundreds of votes after the fact in a futile bid for victory.

People were accused of double voting, voting despite felony convictions or impersonating dead voters. An analysis by Democracy North Carolina, a nonpartisan group that promotes voting, found that many of the challenges were based on faulty information.

“It was not an honest operation,” said Bob Hall, who headed Democracy NC in those years. “It was a deceitful operation.”

For Hall, Terrill’s involvement in the Trump campaign is a red flag that similar tactics may be in the works.

“Terrill was in the middle of the whole thing,” he said. “He has a record in North Carolina of a scam operation to gin up false allegations.”

McGavick, the Trump spokesman, did not respond to a question about Terrill’s involvement in the campaign.

North Carolina also seems to be the president’s favorite venue for amping up tension around voting. He twice encouraged people at his rallies to vote by mail and then try to vote in person in order to test the integrity of the system — a felony under both federal and state law.

More recently, he urged supporters to go into the polls and document “all the thieving and stealing and robbing (Democrats) do.”

Defusing fear, protecting voters

Seeking to inject calm, various officials and voting rights groups issued statements reiterating the rules and vowing swift action against violators. All the while, they wrestled with how much is too much: When do attempts to defuse fear become a megaphone for those who would sow fear?

“A big part of the intimidation is the rumor,” said Alissa Ellis, advocacy director for Democracy NC. “All reports thus far of potential right-wing actions have been vague and opaque.”

Democracy NC runs a hotline for voters (1-888-OUR-VOTE) and puts volunteer “Vote Protectors” at polling sites, particularly in nonwhite neighborhoods. The hotline has seen a big surge in calls compared with previous years.

But most are about routine matters: voters wanting to know where or when to vote, whether they can still register — yes, at any early voting location — or how to request a mail ballot.

Organizers of the Vote Protector effort hoped to attract 500 volunteers to the online training sessions; more than 2,000 showed up. Last week at the final session, 90% of the volunteers were first-timers.

For the most part, the trainers told volunteers, they’ll be answering basic questions from voters or calling the hotline to report mundane issues such as long lines or, at the worst, a ballot shortage. If an individual or group tries to block or intimidate voters, the volunteer’s job is not to engage with them but to call the hotline, the trainers stressed.

“If you’re going to want to confront the intimidator, this is not the volunteer opportunity for you,” said trainer Shelby Sugierski.

What happens, one volunteer asked, if someone shows up with a gun?

“We’ve never had an instance of anyone brining a gun to a voting site before,” said trainer Caroline Fry. “We’re not anticipating it. But if you see that and feel unsafe, call the hotline.”

In fact, North Carolina does not prohibit people from carrying guns in or near polling places — unless the nature of the building itself, say a school, library or courthouse, makes guns off-limits. It’s also legal for individuals or groups to stand outside the 25- to 50-foot buffer zone and wave signs or flags and loudly proclaim their allegiance to their chosen candidate.

They can’t, however, block voters from entering the polling site, distribute misinformation about qualifications to vote, wear uniforms or insignia that resemble law officers’, make threatening statements or gestures or brandish weapons as though to use them.

Between those two clear poles, however, is a world of gray area, where one person’s free speech is another person’s intimidation.

Election officials live in that gray area.

Corinne Duncan, head of Buncombe County’s elections office, said local government leaders began meeting with police and sheriff’s representatives months ago to anticipate situations they might face.

But sometimes there’s nothing police can do.

A few weeks ago, anti-abortion activists shouted at voters dropping off absentee ballots at the Buncombe elections office, across the street from Planned Parenthood. Police came and spoke to the protesters.

But officers couldn’t make the protesters leave because the elections office was not considered a polling site before the start of early voting.

Generally, though, voting is a highly protected activity, as a memo from the NCSBE to county elections offices makes clear.

“The State Board has partnerships with federal, state and local partners who provide assistance, including monitoring and support on the ground,” the memo dated Oct. 12 declares.

“In the event your office becomes aware in advance of a planned march or protest that has the potential to cause a disruption or commotion at the polls, notify the State Board right away, and we will work with our partner agencies to monitor the situation and provide support as needed.”

Victoria Loe Hicks is a contributing writer to Carolina Public Press who is based in Mitchell County. She has previously written for The Dallas Morning News and The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. She is also a CPP board member.