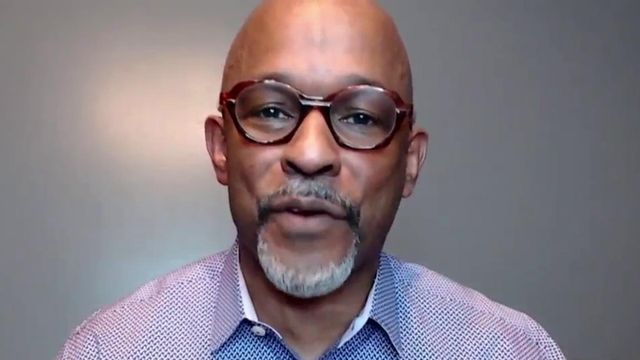

Julian Grace describes 'The Talk' and his own encounter with police

My father’s tone was serious, yet calm. He lectured often; however, the start of this conversation looked and felt different.

“Son, always be respectful to a police officer.”

The statement he uttered ushered me into a common speech delivered in African-American homes called “The Talk.”

The Talk

To sum it up, "The Talk" is a beginner's guide on how to avoid and survive police encounters.

This month, images showing George Floyd panting to breathe while former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin kneels on his neck resurfaced. Chauvin’s trial reinforces the urgency some parents of color feel to have "The Talk."

“I didn’t want to see you get into any problems or get hurt or killed,” said my father.

These conversations on survival are a right of passage. The examples were lived out by my father, who received his guidance from my grandfather.

“It’s based on experiences in our life," said author, speaker and community bridge builder Tru Pettigrew. "Our life experiences suggest this is a way to safeguard and protect ourselves -- that these are the steps we need to take."

In the late 1990s, I would have to follow this road map during a frightening encounter with an officer in my hometown of Indianapolis.

Teenage Julian's encounter

I’m nervous. It’s my first time driving alone. I just got my license, and I’m behind the wheel with my hands on 10 and 2. My seatbelt is on, and I’m even driving a couple of miles under the posted speed limit.

Suddenly, I hear sirens. Red and blue lights reflect off my rearview mirror. I’m nervous, but I’m thinking my driver's education class prepared me for this situation. When an emergency vehicle approaches you from behind, pull to the right side of the road and let the vehicle pass.

I do it, only the squad car doesn’t take the lead, it stays behind me. After a brief second of confusion, I realize those sirens were for me.

In a panic, my mind is racing. What driving rule did I violate? The officer who conducted the stop jumps out of his car and moves toward my vehicle with a sense of purpose.

He asked, “What did you stuff under your seat?”

I’m puzzled, and I say, "nothing.”

“Do I have permission to search your vehicle?” asks the officer.

I tell him yes, and he escorts me out of the car. In a span of less than a minute, about six additional squad cars arrive.

I’m scared. A K9 unit arrives. The dog is sniffing the inside and outside of my vehicle. This goes on for about 20 minutes.

During this process, I’m surrounded by men and women in blue. Neighbors are on their porches, people are standing on the sidewalks and others are in their cars looking at me as officers form a hedge around me.

At that moment I’m embarrassed and scared. The search turns up nothing. I feel so alone. The officer who conducted the stop appears agitated.

He makes his way toward me and says, “I’m going to let you go with a warning for speeding, but next time remember the speed limit is 35 miles per hour.”

His words ignited something inside me. I wanted to protest his unjust stop. He knew I wasn’t speeding, but that wasn’t the issue. He said I stuffed something under my seat, which I didn’t.

Watch WRAL's Black and Blue documentary

In my heart, I believe the officer pulled me over because he thought I fit a profile of someone who didn’t deserve the benefit of the doubt.

Despite my frustrations, I remembered "The Talk" and all the ambition I had to prove my case evaporated. I said, "Yes sir," the officer handed over my license and registration, and I was free to go.

Back to the present

I always wanted to talk to the officer who pulled me over. I wanted him to know I was a good kid and that I never stuffed anything under my seat.

I recently called the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department in an attempt to get the report and find the officer. During my research I discovered there was no report filed because I wasn’t arrested.

I agonize over that day. I felt like I should have done more. I should have reported the incident to the department and informed them that I was unjustly pulled over and treated as if I committed a crime.

It may not have made a difference in my case, but it could help the next teenager who looked like me. But I didn’t.

During my research, I reached out to the former police chief of the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department, Troy Riggs. The law enforcement veteran helped establish a system that identified officers who were frequently the subject of complaints or who demonstrated patterns of inappropriate behavior.

Riggs posed great questions during our interview, such as, “How do you hold a chief accountable if he or she doesn’t know about that conduct?"

According to The Washington Post, only three percent of citizen complaints that allege improper conduct by an officer actually lead to any discipline.

Reading that number will force some to question whether it is worth the trouble to report an officer. I've found there are other ways to address the issue, and that’s with additional conversations.

Bridging the gap between officers and men of color could be helped by having a collective discussion together.

That happened at a barber shop in Cary before the pandemic, when police officers and the African-American community came together to have a dialogue.

Pettigrew, founder of Tru Access, started these talks and witnessed the benefits.

“You have guys saying, 'I never thought I would be this close to a cop.' They are friends now,” said Pettigrew.

The success of those conversations leaves me feeling optimistic but not carefree enough to abandon "The Talk" with my own children.