In rural NC, students gather at hot spots as state seeks larger broadband fix

The grandmother looked at a borrowed tablet and cried.

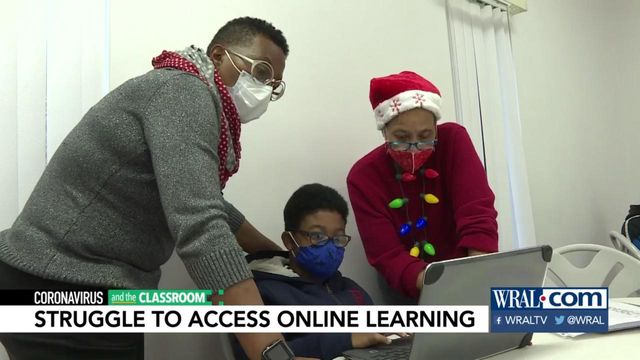

The local school system provides free internet now, so that wasn't the problem. The problem, Evelyn Parker said, was she didn't have the first idea how to help her 9-year-old grandson or the 16-year old she serves as guardian to log on for online school.

Thank God, she said, for the learning pod at First Baptist Church.

Like churches, libraries and community centers across North Carolina, First Baptist partnered with the local school system, giving students a place to come during school hours. Halifax County calls them "learning pods," where teachers go from folding table to folding table, helping small groups of students, elementary through high school.

Some come because they don't have internet at home, a widespread issue in this rural county. Others because they couldn't make virtual school work, internet or not.

"I don't know anything about a computer," Parker said this week. "Ever since (this learning pod opened), it's been a weight off my shoulders."

Altogether, the state estimates 40 percent of North Carolina homes don't have high-speed internet, either because they don't have access in their area or because they can't afford it.

That includes Te’Navion Pitts, and without the learning pod at First Baptist Church, next to a housing project in rural Enfield, the elementary school student sees his reality in black and white.

“I wouldn't be able to get on class," he said. "I would just, just flunk fifth grade."

He wouldn’t’ be alone. Failure rates are up at schools across the state.

Statewide, education officials expect to hold more students back this year than any time in a century.

The challenges of rural internet aren’t a secret.

Companies can't make enough money stretching their services across the farmland or over the mountains that separate homes in less-populated parts of North Carolina. The state, demographers say, has the second largest rural population in the country, after Texas.

When local governments tried to build their own infrastructure, internet companies went to the General Assembly to squash what they called unfair competition. The legislature passed a law in 2011 severely limiting local authority to offer internet.

The change was so effective that the North Carolina Utilities Commission, which can approve new government-backed internet projects if conditions are met, had to comb through its files this week to say whether anyone had even asked to try.

None have.

Government focus shifted instead to public subsidies for internet companies large and small. In 2018, the legislature created GREAT grants to pay for the last few miles it takes to connect rural home, and the program has invested $26 million, enough to connect an estimated 22,000 homes.

Another $30 million is on the way, but competition remains fierce. Of the 126 grant proposals submitted, another company challenged 51 of them and tried to block the funding. After the first round, the state tweaked requirements to make that harder to do, state Broadband Infrastructure Office Director Jeff Sural said.

There are other pots of money, too, with hundreds of millions of dollars flowing nationally from the federal government. Now, Gov. Roy Cooper wants to borrow $250 million for broadband expansion in North Carolina, a generational change that would treat high-speed internet access more like a utility.

The proposal may not get traction with the debt-averse Republican majority in power at the legislature, but General Assembly Republicans have prioritized broadband expansion for years, and the pandemic has only sharpened that focus.

Around the state, private companies are pushing for solutions, too, with and without wires. Eastern Carolina Broadband offers internet via radio signal and has worked with governments in and around Jones County to get their equipment up high enough to work.

Roanoke Electric Cooperative is adding internet fiber in its service areas in a project that could be a game changer for northeast North Carolina.

“It all looks promising,” Halifax County Schools Superintendent Eric Cunningham said this week. “So, in five years, I see a lot. The momentum will not stop. We’ve tasted it. It’s hard to go back to eating bologna when you’ve tasted steak.”

Halifax County Schools distributed more than 300 wireless internet hot spots around county.

Most help students take classes in their homes. Some power the learning pods, like the one at First Baptist Church. Others went to park-and-learn lots, which are exactly what they sound like.

One used to be in a school bus parked at a Dollar General, but the bus' aging power supply kept cutting out, so the county installed routers on telephone poles instead, hardwiring them into the electricity.

Statewide, government and private partners distributed more than 84,000 hot spots around North Carolina, offering the broadband speeds needed for the video chats with teachers that have form the backbone of online school during the pandemic.

But change is slow.

It took until October to get five learning pods up in Halifax County, and the school system plans to add a sixth one soon. Even free internet goes out. Shelia Lowe, director of technology for Halifax County Schools, spends her days bouncing between school buildings and learning pods separated by miles of flat and lonely land.

Service went out in Enfield when WRAL News visited on Thursday.

The county has 2,194 students, and the system office says about 80 percent have access now to broadband internet, thanks to the hot spots. But some places just don’t have cell towers, and a free hot spot wouldn’t do families there any good, officials said.

Assistant Superintendent Tyrana Battle said some students still get paper packets from their schools and phone calls from their teachers instead of online chats.

"These things are all just Band-Aids," Battle said of the hot spots. "We really need fiber here."

Despite connectivity issues, Halifax County schools are online only.

Cunningham said he’d like to reopen, but it’s not safe. A beloved principal – last year’s principal of the year in Halifax County – died over the summer with COVID-19, and Cunningham said he can't persuade enough teachers to get back in the classroom to make it all work.

“We’re responding to the waves,” said Cunningham, who came to Halifax County from the Nash-Rocky Mount school system in 2016. “One of the things that I learned quickly here is the waves are big.”

As Cunningham spoke outside the system office, volunteers gave out sacks of Christmas gifts in the parking lot. Winter coats and school desks were available too, and parents drove up to take delivery.

Like other school systems, Halifax also sends buses around the county at lunch time to deliver meals. One of them stopped a small line of traffic Thursday on N.C. Highway 125, between Halifax and Scotland Neck. A child burst from his home, running so fast that he stumbled in the grass and gravel of his family’s front yard.

He popped up and crossed the highway, then returned home with a sack of food nearly half as big as he was.

Dim fluorescent light in the makeshift school room at Shiloh Baptist Church in Scotland Neck doesn't quite make it into the corners of the wood-paneled walls.

Eight students sit in folding chairs, social distanced and masked up as teachers and an elementary school principal look over their shoulders. Some are on computers. Two use cellphones for video calls with their teachers and to work online.

Seventh-grader Kayla Clark says it’s not so bad on the phone. She has internet at home but likes it better in the learning pod.

“People,” she said. “You’ve got people.”

A table away, a second-grader is focused on a computer screen.

“Mah,” he said. “Mah-Ice. Mice.”

It's a reading exercise. There’s a dial on Zaiquan Young's screen where he can change the letters and build new words. The digital dial clicks like combination lock. Zaiquan's eyes are bright as he looks to Ivory Creecy, an instructional coach at Scotland Elementary Leadership Academy, for approval.

She gives him a thumbs up – and presumably a smile, though who can tell beneath the mask.

Asked how it’s going, Creecy says just that: It’s going.

“It’s something totally new,” she says. “But we are really persevering through it all.”

WRAL Eastern North Carolina reporter Indira Eskieva contributed to this report.