More women fleeing to NC for abortions after fall of Roe

Clinic by clinic, county by county and up to the highest levels of state government, no state embodies the nation’s post-Roe upheaval like North Carolina.

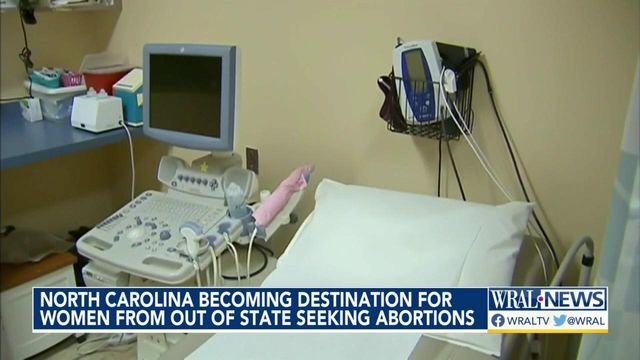

In the eight months since the federal right to abortion was eliminated, leaving states free to make their own abortion laws, North Carolina, where the procedure remains legal up to 20 weeks, has become a top destination for people from states where it is banned or severely restricted. North Carolina experienced a 37% jump in abortions, according to WeCount, an abortion-tracking project sponsored by the Society for Family Planning, which supports abortion rights. Providers in the state performed 3,190 abortions in April. That number soared to 4,360 in August, after Roe fell. It was the biggest percentage increase in any state.

The state’s abortion providers are under strain, with women sometimes having to wait a month for an appointment. In Chapel Hill, nurses at the Planned Parenthood clinic say they often pull into the parking lot to find patients sleeping in their cars. The license plates are from Tennessee, Georgia, even Texas.

The large influx of patients has energized local volunteer networks offering rides, money for clinic fees and places to stay. It has also alarmed anti-abortion activists who in June were rejoicing when the court struck down Roe v. Wade, only to later discover a surge of abortions in their state.

“Right now, people are flocking here because they believe they can take the life of the unborn, and that concerns me,” said Ron Baity, a Baptist minister in Winston-Salem who is president of the anti-abortion group Return America.

The atmosphere around clinics has grown more tense as new activist groups emerge, and as more patients show up. Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat, issued an executive order last year directing state officials to help ensure safety around abortion clinics.

In Raleigh, the capital, a Republican-led state legislature is now considering rolling back the threshold to around 12 weeks or less. Cooper has pledged to veto any new abortion restrictions.

Meanwhile, a half-dozen counties in North Carolina’s rural Piedmont and mountain regions have voted to become “sanctuaries” for the unborn, declaring their opposition to abortion. The designation is largely symbolic, state legal experts said, but the Personhood Alliance, which backs the movement, says such declarations send a message that can lay the political groundwork to help outlaw abortion later.

“We’re preparing for the hardest fight of our life,” said Jenny Black, CEO of Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, which includes North Carolina. “And we’re sober about the realities of how difficult that is going to be.”

The influx of patients was unexpected in this politically polarized place, where lawmakers have been tangling over abortion for years.

The Clinic

One Thursday in early December, Dr. Jonas Swartz rapped on a side entrance to the Chapel Hill Planned Parenthood clinic. He was hoping to avoid the protesters often gathered out front, a protocol that has become second nature since he started practicing at the clinic more frequently to help meet demand.

“Who is it?” asked a voice on the inside.

“Jonas,” he said.

A staff member ushered him in.

Over the next few hours, Swartz saw patients back to back, toggling between two procedure rooms.

At midday, roughly 20 people — patients and their friends and family members — were spread out in the waiting room, many of them napping.

Planned Parenthood estimates that more than one-third of its abortion patients in North Carolina are from out of state these days. But the no-show rate has also climbed.

“It’s just hard to get here,” said Swartz, a Duke Health obstetrician and gynecologist. “It’s a lot. You’ve got to arrange child care. If someone gets sick, if you lose transportation, you may just not be able to get here on the day you thought you were going to.” The volume of patients is higher, Swartz said, and may become more difficult to handle as other Southern states consider more severe restrictions on abortion. “It sort of feels right now like the walls are closing in,” he said.

A federal judge in Texas could order the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to withdraw its approval of mifepristone, a key component in medication abortions, affecting the availability of abortion pills across the country.

Medication was the method for 59% of abortions performed on North Carolina residents in 2020, with surgical procedures accounting for 37%, according to the most recent state data.

Members of the clinic’s staff said they were anxious about the shifting legal landscape. One nurse, Caroline Christopher, wore a gold chain with a coat-hanger pendant — an homage to her grandmother, she said, who had been an activist in the 1970s and wears a matching necklace. “We’re all trying to stay positive,” she said.

Ultimately, the clinic saw two dozen patients that day. A dozen canceled. Since the fall of Roe, the site has treated up to 35 people per day.

Journals that the clinic keeps in the recovery room were filled with entries about challenges the patients had faced.

“I am here from Johnson City, TN (4 hour drive) due to my state not providing the right to an abortion,” one patient wrote. “I have a 3 yr. old son, and am just now to a point in my life where I am stable enough to take care of us comfortably. Another child at this time is just not in the cards for us.”

The Divide

Last year, Tina Marshall started a new group: the Black Abortion Defense League. She was hoping to engage more Black volunteers to work with her to preserve abortion rights. On a clear January morning, Marshall stood in front of a Charlotte clinic yelling, “Baa-aaa-aaa-aaa” at anti-abortion activists, whom she likened to sheep.

Anti-abortion protesters with a group called Love Life shouted through megaphones at women approaching the clinic: “The world says it’s OK to go out and have sex with whoever you want and then just come here and take care of the problem, quote unquote!”

Marshall said she wanted to bolster participation of Black women in an issue that has an especially large effect on their lives. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for 2020, the most recent year available, showed that 52% of abortion recipients in North Carolina were Black, compared with 28% who were white. Hispanic women made up 13%.

The increase in out-of-state patients has supercharged the clash over abortion, activists on both sides say.

The abortion issue is more urgent than ever in North Carolina, said Philip “Flip” Benham, an anti-abortion activist, because “we’ve become sort of a destination state for abortions.”

In many ways, the scenes in front of clinics here are the same as they have been for decades: Protesters who believe abortion is murder shout through loudspeakers and film people arriving at or leaving the facilities. Volunteers use oversize umbrellas to shield patients from the protesters, who they say sometimes physically block patients entering the clinic.

In October, Charlotte police confronted Benham over what witnesses described as his swinging a baseball bat around the driveway of the Planned Parenthood clinic. Benham was charged with undefined criminal activity, according to a police report. Benham said the charges had been dropped.

Benham isn’t focused on the legislative battles in Raleigh because he believes no laws will be changed until Cooper leaves office. “We’re winning this battle in the streets,” he said.

In June in Asheville, Mountain Area Pregnancy Services, which opposes abortion and steers women toward carrying their pregnancies to term, was defaced with red paint, its walls splattered with the message “If abortions aren’t safe, neither are you!” A center worker, Kristi Brown, said it had cost $90,000 to repair the facility and add security.

Last summer, the center received a flurry of calls from women in neighboring Tennessee and even Kentucky — states that had quickly outlawed most abortions after Roe’s overturn — who were seeking abortion appointments and didn’t realize the center doesn’t provide them, Brown said. Even as the volume of those calls diminished, the center last year had a 10% uptick, compared with the year before, in clients who were seeking a range of services, including counseling for patients who had already received abortions, she added.

The Battle Ahead

North Carolina’s political showdown over abortion is personified by two leaders: Cooper and Tim Moore, Republican speaker of the state House of Representatives.

Cooper, a former attorney general, wants to preserve the state’s current law. He has ordered additional protections, including preventing the extradition of anyone involved in carrying out an abortion that is legal in North Carolina.

But Republican dominance in the legislature means the ability to veto is Cooper’s most potent tool. “Our law is restrictive enough in North Carolina right now,” Cooper said in a February interview.

Public polling explains the state’s political friction: A recent Meredith College poll of registered voters found that 57% of respondents wanted to preserve North Carolina’s current abortion law or expand it beyond the 20-week limit. About 35% of those surveyed supported a rollback of abortion access to 15 weeks or less.

Moore has said that a ban after 12 weeks — with some exceptions — is more likely to “garner the necessary support to become law.”

Moore also said in a recent podcast that a swing Democrat, whom he declined to name, was willing to vote for a 12- or 13-week curb. That crossover is potentially significant because House Republicans are one vote shy of a supermajority that would allow them to override a veto.

For now, even North Carolina residents are feeling the effect of bans in neighboring states: When Maria, a 31-year-old who lives outside Asheville, learned that she was unexpectedly pregnant in late June, she knew a baby was more than she could handle. Maria, who did not want to reveal her full name because of her family’s opposition to abortion, was coping with depression and, she says, several other medical conditions.

She called the nearest abortion clinic, which is in Asheville. The wait, she was told, was two months. She then called two clinics in Charlotte, about a two-hour drive away. One never responded. The other said it could take her the following month. She grabbed the appointment. This article originally appeared in The New York Times.