Graves by Gate 6: Thousands tailgated by graves of enslaved men and women outside Carter-Finley Stadium

Imagine walking past a lost burial ground for formerly enslaved men and women every time you went to see a football game.

If you've been to a football game at Carter-Finley Stadium in Raleigh, you don't have to imagine it: It's happened.

For decades, thousands of football fans and players alike unknowingly walked past the unmarked graves of 12 formerly enslaved people. The grave sites were actually part of a broader piece of lost history: Remnants of an old 1800s freedman's village named Lincolnville, which was one of 13 villages built along the outskirts of Raleigh by men and women freed from slavery in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War.

Today, many locals have never heard of the lost community of Lincolnville – and all but two of the original freedman's villages have been wiped from the map of Raleigh.

However, a woman buried in at least one of those hidden graves by Gate 6 helped tell the story of this vanished village.

Grave sites full of glass, bones and remnants from 1850s

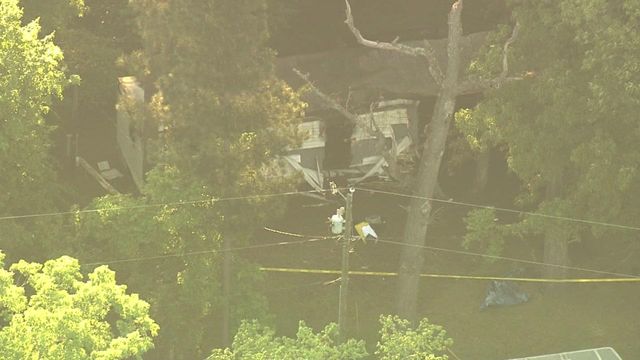

In 2015, North Carolina State University decided to exhume 12 graves from the burial ground, which was obscured in a wooded area near Carter-Finley Stadium's Gate 6.

According to a report on Find A Grave, in the graves were in very poor condition, and the stadium's tailgating areas were "encroaching on the actual graves."

Researchers who excavated the site found bones, skulls, bits of glass and coffin handles just outside the stadium. They used special tools to detect areas where soil was looser and could have been part of a grave. The graves were carefully excavated to include soil that could have once been part of a body.

The contents of each grave were relocated to Historic Oakwood Cemetery in Raleigh.

"We were told that a cemetery was coming from NC State," said Oakwood Cemetery's executive director Robin Simonton. "They simply said it was to expand the Carter-Finley complex."

Oakwood took delivery of pine boxes, roughly 20 inches square and without lids. According to an article in NC State's newspaper The Technician, each box contained shards of broken glass, meaning the coffins were likely covered with glass – a style that predated the Civil War. This told historians some of the grave sites were likely from the 1850s or 1860s, prior to the emancipation.

Others, however, were from the early 1900s – some being residents of the freedman's village of Lincolnville.

In an interview with The Technician in 2015, Simonton said there were "a lot of skulls and a lot of jaws."

The 12 graves were interred at Historic Oakwood Cemetery, where they can be seen today.

"We put them back in that same order they were in, in their original cemetery," said Simonton.

Around a year after Oakwood Cemetery received the graves, a family member arrived saying they believed a loved one had been relocated to Oakwood.

They gave the name of a woman buried in one of those unmarked graves: Emmaline White.

"We then looked up and got her death certificate to see more about her," said Simonton.

She died in 1922. She was a formerly enslaved woman. She had died in Lincolnville.

"[Learning her story] made us that much more motivated to find out as much about her as possible," said Simonton. "We went through the census records and tried to do her genealogy so we could tell her story."

Simonton said Emmaline White has become representative of the community of 12 people buried here.

There's still a lot unknown about the people who were buried at Gate 6. But now, every time Simonton gives a tour of the cemetery, she makes sure to tell Emmaline's story.

"I think now more than ever, we know as a community that these stories of the formerly enslaved are often lost – and it's our obligation to try to tell them," she said.

Vanished neighborhoods: What happened to Lincolnville?

In the years after the Civil War, men and women freed from nearby plantations formed 13 freedman's villages around Raleigh. The city was flooded with over 4,000 'freedmen,' who were starting out life in freedom with no jobs, no homes and no money.

"When the war ended and slavery ended, African Americans were free for the first time," said Carmen Cauthen, a historian and author who specializes in Raleigh's Black history, who recently published a book called Historical Black Neighborhoods of Raleigh.

"They were freed with no money, no anything. And people came from all parts of the state of North Carolina to Raleigh because it was the capital city."

Cauthen says there were several communities known as freedman's villages that were created around what were then the city limits. One of them was Lincolnville.

Citizens of freedman's villages made up around half of Raleigh's entire population – and they pulled together to build homes, churches, schools and businesses.

Lincolnville was among the first four freedman's villages, created even before the Reconstruction began. The others were Method, Oberlin and Brooklyn.

Today, the landscape of Raleigh shows very few hints of those freedman's villages. However, just across a wooded lot from Carter-Finley stands the old Lincolnville AME church. Down the road from there is the freedman's village of Method, where an historic church and Rosenwald school remain standing today.

"[Freed men and women] built a church, and they had a pastor. That's still true today," said Cauthen. "Lincolnville AME church started here, and the community of Lincolnville grew around it."

Today, there are very few remnants of these historic neighborhoods. In Charlotte, the Carolina Panthers' home stadium is also built over a Black community that was destroyed.

"Why are those lands okay to build on, to create entertainment spaces?" asked Cauthen.

The land in Lincolnville was eventually sold to the state, and the residents were told that a prison would be there. However, after the land was sold, the plans changed: The prison was never built and, instead, years later, a football stadium was built.

History hidden by football stadiums across the state

Carter-Finley Stadium is far from the only football stadium hiding lost Black history. Clemson's stadium is also built over a cemetery where enslaved men and women were buried, and the Panthers' home stadium is built overtop another lost Black community. The football stadium at UNC is linked to the brutal history of the Wilmington Massacre.

'Ghosts in the Stadium' is a new WRAL Documentary exploring the hidden history beneath each of these iconic football stadiums.

How to watch Ghosts in the Stadium

Watch on streaming

Ghosts in the Stadium is available for on-demand viewing on WRALDocumentary.com, Amazon Fire TV, Apple TV, Roku and Samsung Smart TV.

Watch on YouTube

The documentary is also available on WRAL Doc's YouTube.

Podcast: Chris Lea shares his personal insights on Ghosts in the Stadium

Listen to Chris Lea explain how he became fascinated with the history hidden by football stadiums across NC and SC.