Fact Check: McCrory says Cooper 'fought cleanup' of coal ash

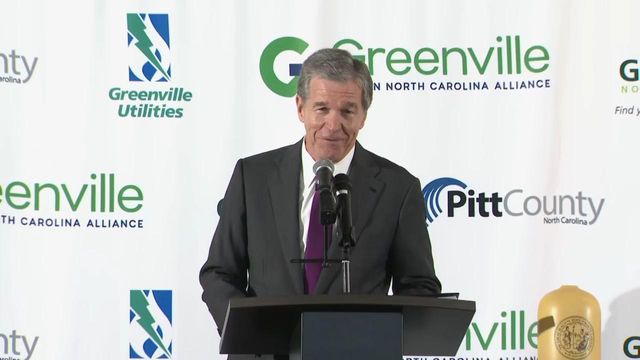

Among the ads Gov. Pat McCrory has put in rotation this month is one attacking Attorney General Roy Cooper over the state's coal ash cleanup efforts.

McCrory, a Republican seeking his second term, faces Cooper, a Democrat, in this fall's gubernatorial campaign.

Ever since a Feb. 2, 2014, spill from a former Duke Energy plant spilled upwards of 39,000 tons of toxin-laced goop into the Dan River in Rockingham County, McCrory has taken heat for his administration's handling of coal ash contamination at sites across the state. This ad seeks to shift blame to Cooper.

"Roy Cooper has been in state government for 30 years," says a man who identifies himself as having lived near a coal ash pit for years. "And like so many politicians, he has ignored the problems. Cooper claims to fight polluters, but he really fought cleanup efforts as the attorney general. He did nothing, while his friends made it harder to prevent coal ash spills."

The accusation that Cooper fought coal ash cleanup is a serious one. Coal ash is linked to contaminated drinking water and is widely regarded as one of the state's most pressing environmental hazards.

THE QUESTION: The claim that a sitting state official – and the state's top law enforcement officer to boot – "fought cleanup efforts" is extraordinary. But can McCrory's campaign point to evidence that shows Cooper standing in the way of cleanup efforts?

SUMMARY JUDGMENT: This is a serious claim, but the backup for it is somewhere between lacking to nonexistent. It earns the lowest rating on our fact-checking scale.

SOME HISTORY: Coal ash is the material left over after coal is burned for fuel. While much of it is inert, in contains heavy metals and other toxins. For decades, Duke has stored that material in unlined pits that are covered over with water.

For years, news about these pits largely flew below the headlines with rare exceptions. While there were lawsuits over a few sites where contamination had leaked into groundwater or surface water, they weren't the headline-grabbing affairs they are today.

In December 2008, a Tennessee Valley Authority coal ash dam broke, sending 1.7 million cubic yards of waste flooding into nearby streams and deluging neighborhoods. Even that spill didn't galvanize action in North Carolina. While a handful of legislators pushed for a bill to better regulate coal ash, they were largely ignored in 2009.

It wasn't until the 2014 spill in the Dan River that coal ash became the front-and-center political issue that it is today. It is fair to say that, before 2014, with rare exceptions, neither Republican nor Democratic lawmakers were focused on cleaning up ash from the 14 locations Duke stored it around the state.

It's also worth noting that Cooper was elected attorney general in 2000, an office he held at both the times of the TVA spill and the Dan River spill. Before then, he was a state lawmakers for 14 years.

McCrory's own history is relevant as well. He is a former Duke executive, and his connections to the company have been criticized by opponents, so it makes sense that he would want to shift focus to what his campaign would say are Cooper's failures.

MCCRORY'S CASE: When the governor's campaign released the ad, they sent reporters a backup sheet, as is common practice, defending the points made in the ad.

Two patterns emerge reading through that sheet. One is that McCrory is pinning actions by lawmakers and McCrory's two predecessors, Democratic Govs. Bev Perdue and Mike Easley, on Cooper. For example, it points to a bill passed by the General Assembly and signed by Perdue in 2009, labeling it an act of "Roy Cooper And The Perdue Administration" without making an effort to show how Cooper, who was elected separately from Perdue and did not have a direct say on the legislation, was involved.

The other theme running through the document is that it frequently misrepresents the stories and other resources to which it links.

For example, that backup sheets summarizes a bullet point from 2014 this way: "After the McCrory Administration Became The First Administration To Sue Duke Energy, Roy Cooper’s Office Negotiated A $99,111 Limited Settlement With The Energy Company Over Groundwater Contamination At Its Coal Ash Basins. The Settlement Was Later Rescinded By The McCrory Administration."

It then links to an Associated Press report about the political back and forth over whether the Governor's Office or the Attorney General's Office should represent the state in litigation over coal ash. The settlement mentioned in McCrory's summary was negotiated by what was then the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, a department controlled by McCrory. While it's true Cooper's office served as counsel in that transaction, which was negotiated before the Dan River spill, it is inaccurate to suggest that the Attorney General's Office negotiated it on its own. It's also worth noting that lawyers for environmental groups quoted in the piece reserve their criticism for DENR.

Pressed for a more direct connection that would show Cooper "fought" coal ash cleanup, McCrory campaign spokesman Ricky Diaz pointed to a pair of News & Observer stories. The most substantive of the two dealt with a complex set of interactions between environmental rules and state laws. Diaz pointed to a paragraph that read, "The 2009 attorney general’s advice concluded that utilities didn’t have to clean up or stop the source of pollution within their compliance boundaries, which reversed the way the rule had been interpreted since 1993. In 2012, the law center asked the Environmental Management Commission to revert to the earlier interpretation, but it refused."

That paragraph was part of a larger narrative and showed the Attorney General's Office providing advice about the state of the law, rather than advocating for a particular policy one way or the other. The other story Diaz cited was a brief in which Cooper's primary challenger attacked him based on the first report.

"These are all examples of actions taken or opportunities missed that compounded the problems, delayed cleaning up coal ash and made it harder to prevent spills. Roy Cooper had every opportunity to address the problems in his capacity as attorney general, but didn't," Diaz insisted.

COOPER'S RESPONSE: When asked for a response to McCrory's ad, Cooper's campaign spokesman said, "What a baffling and ridiculous claim. The McCrory campaign is simply pointing fingers and trying to distract from accusations by a top state scientist that the governor's administration is deliberately misleading the public.

"North Carolina families deserve to know that their drinking water is safe. Roy Cooper has a long record of standing up for North Carolina families against the big utilities, and he will continue to hold them accountable as Governor."

OTHER TAKES: Before going further, it bears repeating that coal ash has a decades-old history in North Carolina, and its recent history of management is complex and hardly covers anyone involved with glory. But the question for this fact check is whether Cooper "fought" coal ash cleanup, as this ad alleges.

Teasing apart the policy from the politics of this is doubly difficult due to what has been a more than two-year run-up to this fall's general election campaign, in which interactions between Cooper's Department of Justice and McCrory's Department of Environmental Quality, the agency that was once DENR, became increasingly contentious and colored by the upcoming campaign.

That's especially awkward because Cooper's department is supposed to function as the state's law firm, providing legal counsel to all of its agencies. That relationship has been frayed throughout the campaign on a number of cases, especially where Cooper took positions different from the administration on issues such as the controversial law known as House Bill 2 or voting rights.

But did Cooper or his lawyers somehow deviate from administration policy in such a way that coal ash cleanup would be hampered?

One of the most logical groups to weigh in on this question would be the Southern Environmental Law Center, a group that has been in the thick of the litigation over coal ash and has been critical of the state's recent efforts on that front.

"Unfortunately, we can’t as a nonprofit help with this article about an election ad," said Kathleen Sullivan, a spokeswoman for the group.

A broad reading of the group's statements on coal ash, such as a timeline of recent litigation, finds virtually all of its criticism focused on the McCrory administration.

Many environmental groups are perceived as liberal, or at least tacitly aligned with Democratic candidates and causes. One that has been vocally critical of Cooper's handling of some environmental work, particularly with regard to regulating rate increases, has been N.C. WARN, a group that describes itself as "tackling the climate crisis – and other hazards posed by electricity generation." It has gone so far as to take out advertisements critical of Cooper to push him to do more on the regulatory front.

Jim Warren, N.C. WARN's executive director, said that, although his group has not been a central player in the coal ash saga, "we've been tracking it pretty closely."

Warren said you could build a plausible case that many leaders in North Carolina, including Cooper and McCrory, did not focus on coal ash until the 2014 spill.

"But the statement that he (Cooper) fought cleanup, that's a clunker to me," Warren said. "I just don't see any support for it."

In years past, the North Carolina branch of the Sierra Club has endorsed McCrory for mayor. They have endorsed Cooper in this year's campaign for governor mainly, said state director Molly Diggins, on the strength of his work pushing to clean up air pollution.

"From our position, the McCrory administration has actually made it more difficult to get the cleanup issues resolved," Diggins said.

If, she said, Cooper or his department bears any responsibility for slowing the cleanup, "it would be as a lawyer for the administration."

Robin Smith, a lawyer and former DENR assistant secretary under Perdue and Easley, now frequently writes about environmental issues, including coal ash. Before moving to DENR, she was a special deputy attorney general in the Attorney General's Office before Cooper took over, concentrating on environmental policy.

"The only thing I can say about that is I never came across anything that elevated that issue (coal ash) to the level of the attorney general himself, he or his predecessors really," Smith said.

As with Diggins, she said the Department of Justice's main role was providing legal advice to DENR based on the current state of laws and regulations, not driving policy one way or the other.

"I didn't come across anything where any attorney general along the line took an independent position," she said.