Fact check: Goldberg says the First Amendment 'doesn't allow you to willingly lie'

The co-hosts of ABC’s "The View" took up the topic of Fox News coverage during a recent show — specifically its coverage of former President Donald Trump’s false assertions that the 2020 election was fraudulent and its reports about the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol.

Co-host Whoopi Goldberg asked why Fox’s coverage isn’t considered tantamount to "recruiting" and "radicalizing."

"To me, this should be against the law," Goldberg said March 8. "You should not be able to lie to the American people knowingly. And, you know, it’s one thing if you made a mistake and you didn’t know. But we've heard for five or six years now, you know, the media was a lying sack of doo. They were fake news. … So how come? What do we do as Americans to say this is not okay?"

Another co-host, off-camera, responded, "It's the First Amendment."

Goldberg countered, "The First Amendment doesn’t allow you to willingly lie."

Goldberg’s comments came as Dominion Voting Systems is suing Fox News for defamation over some of its hosts’ comments questioning the reliability of Dominion voting machines following the 2020 election.

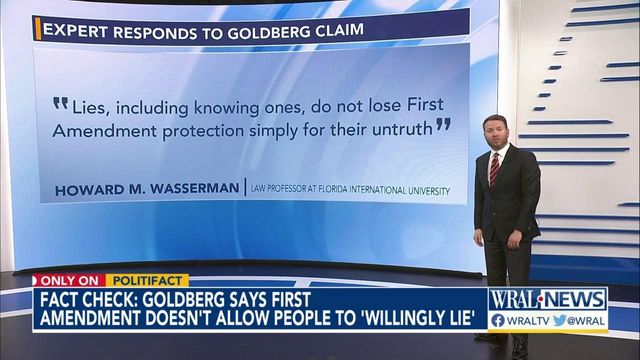

A reader asked us to look into whether Goldberg was right on the constitutional question. Legal scholars told us that she is mostly off base.

"Lies, including knowing ones, do not lose First Amendment protection simply for their untruth," said Howard M. Wasserman, a law professor at Florida International University.

A spokesperson for "The View" did not respond to PolitiFact’s inquiry.

Some carve-outs from constitutional protections for lying

Experts said that for some types of speech, lying is not constitutionally protected, but these are relatively narrow exceptions. Examples include:

- Libel. To win a libel case, the standard a plaintiff needs to meet is high. In the 1964 Supreme Court case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, a majority found that the plaintiff would need to demonstrate that the defendant knew a statement was false, or was reckless in deciding to publish the information without investigating whether it was accurate.

- Incitement. The bar for finding that speech incites violence is also high. According to the 1969 Supreme Court case Brandenburg v. Ohio, speech is generally protected unless it is "directed at inciting or producing imminent lawless action" and is "likely to incite or produce such action." The speaker’s intent matters, and license is granted for rhetorical hyperbole, metaphor, jokes and overstatement.

- False statements in government proceedings. Telling a lie in court could be charged as perjury, and lying to the FBI could result in criminal charges.

- Untruthful commercial speech. In general, commercial speech — speech by businesses, often used to sell products — is granted less protection than other types of speech. The Federal Trade Commission has the authority to regulate deceptive commercial speech, and charities can be charged with fraud if they lie about where donations are going, said Nicole Ligon, a visiting law professor at Campbell University and a former supervising attorney of Duke University School of Law’s First Amendment Clinic. This principle was enshrined in the 1948 case Donaldson v. Read Magazine, in which the Supreme Court allowed the postmaster general to refuse to service a company that had been using the mail to obtain money through a falsely promoted contest scheme.

For the most part, lying is protected speech

Beyond these categories, though, everyday lying has generally been found to be protected by the Constitution.

In the 2012 Supreme Court case United States v. Alvarez, the justices ruled that content-based restrictions on speech are almost always invalid. In Alvarez, the high court struck down a law that had made it a crime to fraudulently claim to have received certain military awards for valor.

"Five of the justices agreed that lies ‘about philosophy, religion, history, the social sciences, the arts, and the like’ are generally protected," said Eugene Volokh, a UCLA law professor.

Volokh said that a separate holding of the Sullivan case was that "even deliberate lies, said with ‘actual malice,’ about the government are constitutionally protected."

State-level laws targeting false political speech have also run into turbulence in the courts.

In 2016, an appeals court ruled unconstitutional an Ohio law that prohibited the dissemination of false information about a political candidate in campaign materials during the campaign season. The decision said that the law amounted to "content-based restrictions targeting core political speech that are not narrowly tailored to serve the state’s admittedly compelling interest in conducting fair elections."

A major reason for protecting lies, experts said, is that the government will not necessarily be an honest judge of what is truth and what is a lie. Volokh said there is continuing concern among jurists about following in the path of the Sedition Act of 1798, a law that banned malicious lies about the government.

The Sedition Act, which was allowed to expire in 1801, would be viewed as unconstitutional under modern First Amendment law, Volokh said, "because it requires the government to decide what’s a lie about it and what’s not — a decision that will often be made inaccurately and self-servingly."

Wasserman agreed. "We do not want to empower the government to decide what is truth," he said. "It would be too easy to label certain political opinions or framings as ‘untrue’ and subject to government silencing."

A broadcaster like Goldberg benefits significantly from protections for lying, Ligon said.

"Talk show hosts are often given leeway, consistent with the First Amendment, when it comes to their speech, in part because they are understood to be entertainers," Ligon said.

Ligon said that both Tucker Carlson on the right and Rachel Maddow on the left "have successfully defended defamation claims."

In the 2021 case Herring Networks v. Maddow, a federal appeals court ruled on a defamation claim stemming from a segment Maddow had aired on her MSNBC show. The segment contained the claim that an employee of One America News Network was "also being paid by the Russian government to produce government-funded, pro-(Vladimir) Putin propaganda for a Russian government funded propaganda outfit called Sputnik."

The court ruled that the statement was "obvious exaggeration, cushioned within an undisputed news story." The ruling went on to say that Maddow’s statement was "well within the bounds of what qualifies as protected speech under the First Amendment. No reasonable viewer could conclude that Maddow implied an assertion of objective fact."

PolitiFact ruling

Goldberg said, "The First Amendment doesn’t allow you to willingly lie."

For the vast majority of speech, the First Amendment considers lies to be protected speech.

There are exceptions to this general rule, but they are limited. In libel and incitement cases, for instance, the judicial bar for proving harm is high, meaning that most types of political speech cannot be challenged successfully in court.

We rate the statement Mostly False.