Nurses are on the virus front lines. But many schools don't have one.

As the lone nurse for her school district in central Washington state, Janna Benzel will monitor 1,800 students for coronavirus symptoms when classrooms open this month, on top of her normal responsibilities like managing allergies, distributing medications and writing hundreds of immunization plans.

“I’ll have to go to these schools and assess every sniffle and sneeze that could potentially be a positive case,” she said. “I just don’t know if I can do it alone.”

School nurses are already in short supply, with less than 40% of schools employing one full time before the pandemic. Now those overburdened health care specialists are finding themselves on the front lines of a risky, high-stakes experiment in protecting public health as districts reopen their doors amid spiking caseloads in many parts of the country.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that every school have a nurse on site. But before the outbreak, according to the National Association of School Nurses, a quarter of American schools did not have one at all. And there has been no national effort to provide districts with new resources for hiring them, although some states have tapped federal relief funds.

Washington state is one of the places where nurses are a rarity in school hallways, with 7% of schools employing one full time, and nearly 30% of districts having one available for no more than six hours per week. Like Benzel, many are being asked to do more than ever before, with little in the way of new resources, training or backup.

In some places, administrators have been scrambling to get more nurses into schools. New York City, the nation’s largest district and one of the few big cities planning to physically reopen its schools on the first day back, went on a hiring spree after the city’s powerful teachers’ union said its members should not return to classrooms without a nurse in each of the city’s roughly 1,300 school buildings.

Mayor Bill de Blasio said last week that the city had finally secured enough nurses to fulfill that demand, less than a month before the scheduled start of in-person instruction.

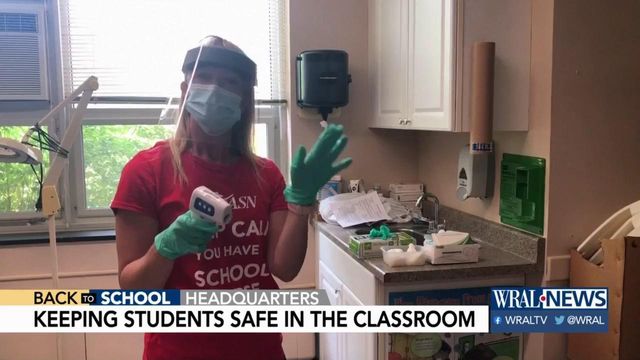

Those nurses will be charged with evaluating children for coronavirus symptoms and determining whether they should report to an isolation room away from other students and staff members, and communicating with parents already anxious about dropping their children off at school.

“It’s weird that it takes a pandemic for people to be like, ‘Oh, look at that, what you do is useful,’” said Tara Norvez, a school nurse in New York City. Norvez said she was looking forward to the start of the school year, as long as there was enough personal protective equipment and other safety measures in place.

“What we are going to do is just step up our game,” she said.

Across the country, though, concerns are growing over the ability to prevent the spread of infections, with outbreaks already emerging in schools that have reopened, requiring mass quarantines and even shutdowns.

Nurses fear they may contract the virus, and worry whether specially designated isolation rooms and personal protective equipment will be enough to contain outbreaks.

“Most school nurses are the only health care experts in their school community able to understand infection control and do disease surveillance,” said Linda Mendonca, president-elect of the National Association of School Nurses. “But not every school has a nurse who’s going to look after the children and staff. You need that expertise as a resource to safely reopen schools.”

In Washington, some nurses have been actively involved in the planning process for reopening schools, but most have been called in only after the decisions were made, or were asked to review plans already in motion, said Amy Norton, an administrator with the state’s school nurse corps, which helps provide smaller districts with nursing services.

“School districts are going, ‘Oh yeah, our nurse can do that,’ and just keep adding on these responsibilities,” Norton said. “They don’t understand that we don’t have a nurse in every building. We don’t have the staffing to cover all of these new needs, like training staff on PPE and educating families on how to check for symptoms.”

In Enid, Oklahoma, where schools reopened last week with five-day in-person instruction, Karry Easterly, the head nurse at an elementary school, said she was confident in the district’s plan despite a growing number of positive virus cases in the community.

To prepare, she said, the district spent about $200,000 on protective equipment, installed plexiglass around the desks of school secretaries, ordered thermometers for teachers, and worked with nurses to create isolation rooms for sick students.

“We know things are going to happen, but the kids need to get back in school,” she said. But Easterly voiced concern about schools in nearby districts where the health protocols were considerably more lenient, including the school that her son attends, which lacks a nurse.

“To me, it’s unreasonable,” she said. School nurses in Suffolk County on Long Island, New York, are better prepared for the new academic year than most. Every building has a nurse on site, and they have worked closely on reopening protocols, said Holly Giovi, an elementary school nurse in the Deer Park Union Free School District.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo has said schools across New York can reopen in the fall, and Giovi expects her district to offer in-person, remote and hybrid instruction models, with strict social distancing and face mask requirements.

“A plan is still coming together, even though we’re at the eleventh hour,” she said.

Giovi has already divided her nurse’s office into separate areas for triage, assessment and isolation. Her district appears to be on track to have enough protective equipment, and she supports the federal recommendations for children to be screened at home each morning before school, “even though I know that parents can lie,” she said.

But Giovi said she remained concerned about ventilation in older school buildings that lack air-conditioning, despite the district’s promises to ensure sufficient filtration and fresh air through open windows.

“I’m worried I’m going to be taking care of teachers passing out from heat exhaustion as much as I am about them coming down with symptoms of COVID,” she said.

Not all school nurses are willing to wait and see how things play out.

In July, Amy Westmoreland resigned as an elementary school nurse in the Paulding County School District in Dallas, Georgia, because of its decision to make masks optional, while requiring that she tend to both healthy and symptomatic students in a small clinic room.

“How could I do my job protecting children if I were to have been infected and made them or their family sick?” she said. “I would not be able to live with myself.”

This month, widely shared photos showed students without masks in packed hallways in the district’s North Paulding High School, and nine students and staff members tested positive for the virus, prompting the school to shift classes online.

“It’s truly my worst fear that I knew would probably happen,” Westmoreland said. In some districts that are not planning to teach in-person classes, nurses are out of work for the time being. The Palm Beach County Health Care District in Florida furloughed about 140 school nurses and health technicians this month, after the county school district decided to teach online until further notice.

But some other large districts set to teach only online are continuing to provide health care. As the school nurse administrator for Columbus City Schools, Kate King is responsible for the health of 50,000 students and 10,000 staff members in Ohio’s largest district.

Aided by more than 100 nurses, she has created immunization plans and developed online platforms for connecting with families so students, especially those with chronic illnesses like asthma and diabetes, can remain healthy while learning remotely.

“When school buildings are shut,” she said, “we’re still reaching out to make sure their health care needs are met.”