Human tests at Duke prove promising for coronavirus treatment

The drug being touted as one of the biggest medical breakthroughs so far in the coronavirus pandemic has connections to both major research universities in the Triangle.

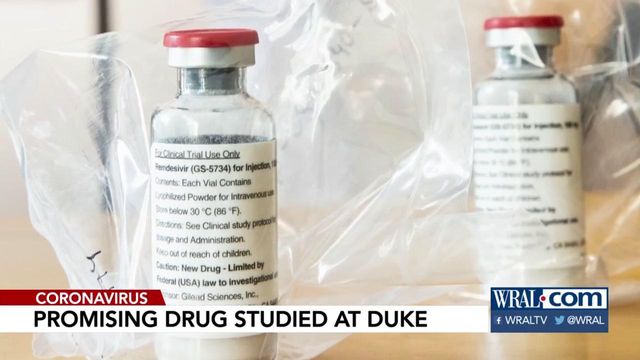

Remdesivir, an anti-viral drug manufactured by a company called Gilead Sciences, originated in a lab at UNC Hospitals six years ago. It was first studied on Ebola patients.

In recent months, it had some of its first tests on humans at Duke University Hospital.

Duke was one of 47 hospitals in the United States and 68 worldwide to participate in the study. The trial began in February. and preliminary results were released on Monday. About 20 Duke patients took part.

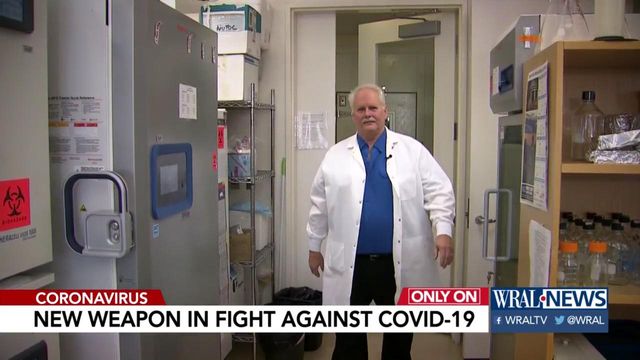

"People got better quicker," said Dr. Cameron Wolfe, an associate professor of medicine who studies infectious diseases at Duke. "People were leaving the hospital four to five days quicker than what they were doing otherwise."

In the double-blind study, Wolfe and his colleagues did not know which patients got the drug and which got a placebo.

"It was the first break in that study that actually allowed us to look at all of our data and say, 'We’ve got a really positive signal here already,'" Wolfe said.

Duke's results reflected what the overall study showed – patients recovered in 11 days instead of 15, and the death rate dropped from 11.6% to 8%.

"It looks to be quite clear that the sooner you can get this medicine, the better you will probably do," Wolfe said. "That’s true of any viral infection, so no surprise that’s the case here as well."

Duke fast-tracked the study.

"It ran for about a month. That in itself is pretty quick by any standards of multinational study," Wolfe said. "It typically takes many months, if not years."

Now, Wolfe and others hope the FDA will fast-track a path to approve the drug for more widespread use. The agency can invoke the Emergency Use Authorization clause during a pandemic when a drug shows promise. Otherwise, it takes years for a drug to be approved.

Because the study was so limited, doctors don't know what impact the drugs will have on people with underlying health conditions, children or women who are pregnant.

"(For a) healthy person with no underlying conditions, fairly young, it is probably worth a shot," Wolfe said.

He said he's proud and humbled to be part of the team making progress against the coronavirus.

"Literally everyone was trying to team together to make it work," he said, "and to get a positive result at the end of it, that’s outstanding."