Can you spot a fake? AI-generated political attacks ramp up as elections near

North Carolinians got a glimpse into the future of political advertising last year when a mysterious political group commissioned a television ad attacking Republican congressional candidate Bo Hines.

The ad by a GOP primary opponent featured an artificially-generated image of Hines mouthing words that he said to a newspaper reporter for a print article. Hines didn’t dispute the content of the comments, which were intended to portray him as a liberal, but he bristled at the use of a fake rendering of him to portray him speaking. Hines’ campaign called the false portrayal “defamatory” and said it defrauded voters. The Republican won the primary but ultimately lost a tight general election race.

Since then, artificial intelligence has advanced and its use in political ads has exploded.

In some cases, audio and video that has been completely fabricated using generative AI looks and sounds completely authentic. And it’s now being used in campaign ads at the highest levels of U.S. politics. Misinformation experts fear the technology could be used to tip the scales of elections across the globe.

“Being an informed electorate just got a lot harder,” said Amanda Sturgill, an Elon University journalism professor and author of “Detecting Deception: Fighting Fake News.”

Misleading ads aren’t new to politics. But historically, technological limitations prevented ad creators from replicating a politician’s voice or physical likeness. If a political group wanted to create an unflattering picture of an opponent, they had to alter an existing image. If they wanted compromising audio of an opponent, they had to alter or edit existing recordings.

Emerging AI tools now afford Washington some of the same powers as Hollywood.

“You can actually put stuff into videos or into photos that wasn’t there to begin with,” Sturgill said. “But you can also make something whole cloth out of nothing.”

And that’s what some are doing. In February alone, at least three AI-generated clips emerged on social media in separate smear attempts. The so-called deepfakes were meant to make people think politicians said something they never said.

The day before Chicago’s mayoral election, an anonymous social media user posted artificial audio of a candidate allegedly saying that police officers used to kill civilians and “nobody would bat an eye.” Another social media user posted a video that falsely portrayed President Biden criticizing transgender people. Another altered video falsely depicted U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Massachusetts, saying Republicans should be restricted from voting in the 2024 presidential election, the Boston Globe reported.

Over the past six months, the AI-generated attacks have ramped up:

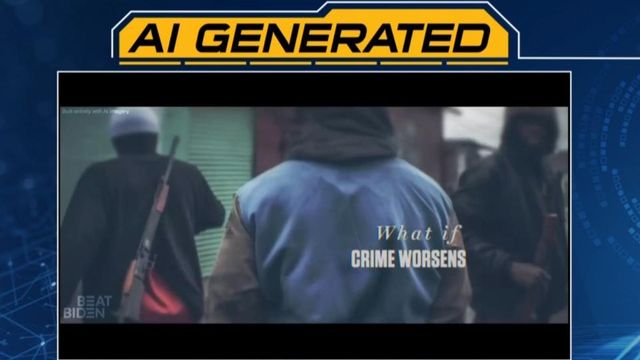

April: The Republican National Committee launched a video ad against Biden that features AI-generated imagery of desolate city streets and migrant caravans. The RNC included a watermark on the video disclosing that the ad was “built entirely with AI imagery.”

May: Never Back Down, a political action committee that supports Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis for president, launched a video ad that includes AI-generated video of military jets flying over a DeSantis campaign event, Forbes reported.

June: DeSantis’s presidential campaign released an ad on social media attacking former President Donald Trump using AI-generated images of Trump hugging Dr. Anthony Fauci, the former director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases who was a controversial figure during the Covid-19 pandemic.

July: Never Back Down, the pro-DeSantis super PAC, used AI to mimic Trump’s voice in a television ad and made it seem like a recording of the former president bashing Iowa’s governor.

September: In Slovakia, altered audio released two days before the presidential elections falsely purported to capture a candidate plotting to rig the election, Wired reported.

Republicans and Democrats alike have condemned campaigns that use AI to deceive voters. For instance, U.S. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, R-Georgia, called on the DeSantis campaign to take down the fake photos of Trump and Fauci.

And yet, the use of AI in political ads is only expected to increase. U.S. Sen. J.D. Vance, R-Ohio, who called the fake Trump photos “completely unacceptable,” posted on social media: “We’re in a new era. Be even more skeptical of what you see on the internet.”

Regulation and free speech

Federal laws don’t prohibit the use of AI to create misleading audio or video in political ads. The politically appointed Federal Elections Commission is exploring regulations for such content but hasn’t implemented any rules that would curb it.

Many states have enacted laws that prohibit the use of deepfakes against private citizens. But only a handful — California, Minnesota, Texas, Washington and Wisconsin — have provisions specifically related to election campaigns, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, which tracks laws passed in each state.

To help viewers, Google and YouTube announced last month that they’ll require users to disclose whether their videos feature synthetic content. A pair of Democratic lawmakers — U.S. Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota and U.S. Rep. Yvette Clarke of New York — sent a letter to other companies earlier this month urging them to do the same. They asked for executives at Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, as well as X, formerly Twitter, to respond by Friday.

“With the 2024 elections quickly approaching, a lack of transparency about this type of content in political ads could lead to a dangerous deluge of election-related misinformation and disinformation across your platforms — where voters often turn to learn about candidates and issues,” Clarke and Klobuchar wrote. Each has filed bills that would require all political ads to disclose the existence of AI-generated content.

Some have opposed the idea of regulating AI-generated political content, saying it’s unnecessary or that it could infringe on free speech rights. Ari Cohn, an attorney at think-tank TechFreedom, has dismissed claims that AI-generated content poses a unique threat to democracy.

“We’re not standing here today on the precipice of calamity brought on by seismic shift,” Cohn said during a Sept. 27 meeting of the Senate Rules and Administration Committee, which Klobuchar chairs.

“AI presents an incremental change in the way we communicate,” he said. “There is no indication that deepfakes pose a serious risk of materially misleading voters and changing their actual voting behavior.”

Allen Dickerson, a Republican member of the FEC, believes AI-generated images that grossly misrepresent political candidates would run afoul of existing regulations.

“Lying about someone’s private conversations or posting a doctored document or adding sound effects in post-production or manually air-brushing a photograph — if intended to deceive — would already violate our statute,” Dickerson said during an Aug. 10 meeting.

Dickerson said hopes any new FEC regulations are targeted at fraudulent activity, specifically, rather than the general use of AI-generated content. Imprecise rules could chill free speech, he said.

Local feedback

In the Triangle, voters expressed mixed feelings about the issue during interviews with WRAL. WRAL showed individual voters the DeSantis campaign’s images of Trump hugging Fauci, and asked for their reaction before disclosing that the pictures were AI-generated. Most were skeptical the embrace ever happened.

“I don’t think Donald Trump ever supported Fauci,” Thea Robarge of Raleigh said standing outside a grocery store in western Raleigh.

Raleigh resident Antwan Orr, who wasn’t sure whether the images were authentic: “With technology these days, you never know what to believe.”

Voters were split over whether the government should step in to regulate AI-generated images, such as those of Trump and Fauci. Randall Bain, a Democrat from Raleigh, said: “We should have standards and a good leader should abide by those standards.”

Outside a Durham voting center, Jay Heikes of Durham worried that regulations might be applied unfairly: “How quickly does that become a First Amendment question of, ‘this AI-image is OK and this one isn’t?’”

Voters also had different ideas on whether their preferred political candidate should use AI to try to gain an advantage at the polls. Robarge said she’d be upset if her preferred candidate used AI-generated content to attack their opponent: “A campaign can be easily won just [by] providing the truth.”

Orr said he’d want his preferred candidate to win “by any means necessary,” adding, the “United States has been like that for how long now?”

How to spot fakes

While generative AI has improved — and can fool many voters — its creations aren’t always perfect.

With audio clips, is the person’s delivery fluid? If the words sound choppy — or if the speaker places an emphasis on an unnatural spot in a sentence — that might be a sign the clip was artificially-generated.

If the audio is paired with video, check to see if the sound synchronizes with the movement of the person’s lips. PolitiFact, WRAL’s fact-checking partner, detected several fakes after noticing that audio didn’t match up with the featured person’s mouth movements or facial expressions.

Meanwhile, AI image-generators sometimes fail to account for key details.

“Often it’s stuff that’s in the background in the image,” said Sturgill, the expert from Elon.

“To save computational power, they’ll spend a lot of effort on making the front part of the image look good,” she said. “But stuff in the background will be nonexistent, or just wrong.”

For instance, in the background of the image of Trump hugging Fauci, the letters on a White House sign are all jumbled. The sign doesn’t say “White House” or “Washington,” as it should. The sign shows the letters: “MEHIHAP.”

Ad-makers: Worry about rogue actors

Some candidates and companies aren’t willing to sacrifice their reputation just to please one client.

Pia Carusone, managing director and president of SKDK Political in Washington, said her consulting firm wouldn’t create a fake image akin to the one fabricated to showTrump hugging Fauci.

She said her company’s clientele has “a much stricter interpretation of what's right and wrong in that regard,” Carusone said. “Our clients, they don't want to win at any cost. They want to win based on fair rules.”

Nuno Andrade hears the same thing from clients of Media Culture, a Texas-based marketing firm where he’s chief innovation officer. The group primarily works with political candidates in local elections. Clients are curious about how AI works, he said, and scared of how it could be used against them.

“It is something that we've gotten some questions about and, mostly, from a defensive standpoint,” Andrade said.

The targets of AI-generated attack ads may never actually find out who’s responsible for the content, he warned. Generally speaking, larger ad firms have reputations to protect. They have businesses to run, and are careful to avoid legal trouble.

In the political arena, it’s possible — if not likely — that the most egregious abuses of generative AI come from an anonymous source.

“It doesn't take someone with deep pockets, who can hire 100 people in a basement, to do these things,” Andrade said.

All it takes, he said, is “the guy next door with a computer and a passion.”