Analysis: Expanded private school voucher program would cut public school funding by more than $200 million

A proposed more-than-doubling of North Carolina’s private school voucher program would reduce public school funding by more than $200 million, according to an analysis from the state’s Office of State Budget and Management.

Meanwhile, the state would end up spending $277.5 million more overall on private schools through the expansion The analysis doesn’t include the potential federal local and funding impact associated with the voucher program’s expansion.

Private school vouchers, called Opportunity Scholarships in North Carolina, are checks written by the state, on behalf of qualifying families who apply for the voucher, to a private school. The child must apply to the private school and be accepted to qualify.

Lawmakers are proposing expanding eligibility for private school vouchers — a move that would cost the state more than half a billion dollars annually by the end of the decade. If approved, it would likely lead to a decrease in funding for public schools. The Office of State Budget and Management analysis, released this week, is the first state estimate of the financial impact of legislation that’s likely to pass later this year.

“It’s not easy to generate one number here,” said Robert Luebke, director of the Center for Effective Education at the John Locke Foundation. “Because when you’re talking about estimates on the impact, you’re talking about short-term and long-term.”

Luebke, who supports the voucher program, thinks the loss to public schools could be bigger, if they have to cut more staff over time. But they could also be smaller at first, because private schools may not have the space to expand so quickly or open up quickly to begin enrolling tens of thousands more students.

The analysis also cuts off before even more expansion is expected, said Kris Nordstrom, senior policy analyst at the North Carolina Justice Center’s Education and Law Project.

“They’re underestimating the fiscal impact, which is going to get worse and worse every year,” Nordstrom said.

Plus, he said, schools’ needs aren’t completely proportional to enrollment.

“It could save on building costs if you would otherwise be a growing district or something like that,” said Nordstrom, who opposed the voucher program. “But it sort of underestimates the impact on the overall budget. There are fixed costs.”

Many, especially rural, districts are shrinking.

But there are also non-fiscal costs, Nordstrom said, like fewer people being invested in the health and success of the public school system, which the vast majority of state students attend. Private schools are selective, he said, and may not mirror the demographics of their communities.

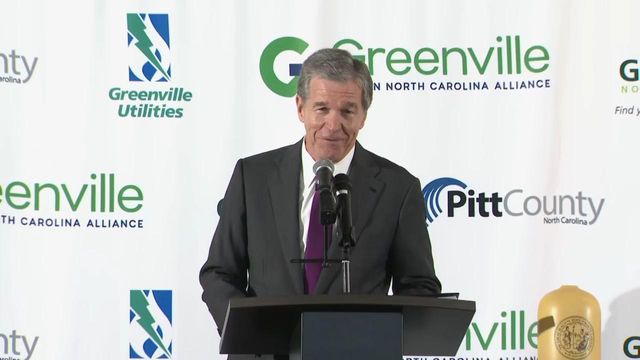

Senate Bill 406 and House Bill 823. The bills, sponsored by Republicans, are identical pieces of legislation that have passed through each chamber’s education committees and could have enough support to override a veto from Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper.

The bills would more than double spending on the state’s private school voucher program from $133.3 million this year to well more than $400 million in the 2024-25 school year and well more than a half a billion dollars annually by the end of the decade. It would expand eligibility for vouchers from just lower-income families to families of all incomes, while requiring at least 50% of funds to go to children whose families qualify for free or reduced-price school meals. The lowest-income families would receive more than $7,000 in a year, while the wealthiest would receive more than $3,000 in a year, starting in the 2024-25 school year. For the first time, students already attending a private school would also be eligible for the vouchers.

Research is mixed on the impact of private school vouchers on student achievement, with some studies showing performance declines in some states among students who transferred to private schools while studies in other areas showed higher graduation rates among voucher recipients. No testing data exist to compare outcomes in North Carolina, and some research done here did not involve randomly selected students.

The Office of State Budget and Management’s analysis projects the voucher expansion’s impact during the 2026-27 school year. It assumes 50% of the new voucher recipients will be public school students transitioning to a private school.

If that’s the case, 26,522 students would leave public schools for private schools — just less than 2% of public school students. That would result in $203.8 million less in state funding for public schools, while requiring only $138.7 million in new school voucher funding for those public school students. The state would spend another $138.7 million on vouchers for students already attending private schools.

Because school funding is largely based on enrollment, public schools would lose several thousands of dollars for every student who leaves.

The analysis only considers the state funding impact. Federal funding is also often based on enrollment, and public schools would lose federal money for each student who left, as well.

The complex nature of analyzing the financial impact of the voucher program expansion highlights a bigger problem with school funding, Luebke said.

“What it really underscores is the need to totally revamp how we fund schools,” he said. “I think that’s ultimately where things are going.”

Luebke thinks school funding may change from the state’s relatively rare “allotment system” to one that weighs students’ needs, such as if they have a severe disability. It’s what Luebke and others, including Senate Bill 406 sponsor Sen. Michael Lee, R-New Hanover, have called “backpack” funding, or funding that follows each student wherever they go to school.

But Nordstrom cautioned against framing the state’s per-student funding as an individual investment with private return for families. Public schools are a public good, he said.

“Having folks that can work across social groups, work across class, work across race. Having people that are self-sufficient. People who are knowledgeable participants in our democracy. People who are discerning consumers of information,” Nordstrom said. “These are all collective benefits.”