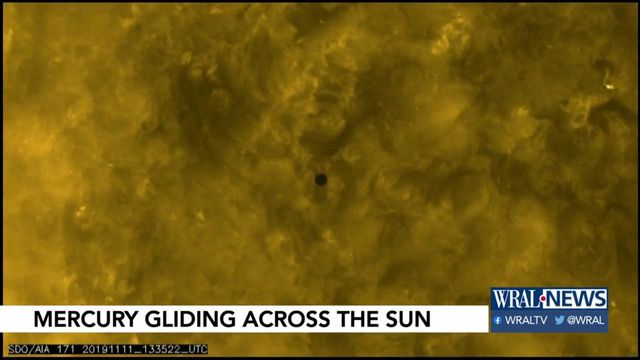

See the rare transit of Mercury on Monday

On Monday, Nov. 11, Mercury will pass in front of the Sun. Unlike solar eclipses which are measured in minutes, transits of inner planets like Mercury are measured in hours, so there will be plenty of time to experience this.

Posted — UpdatedTransits are essentially partial eclipses. Instead of the Moon coming between us and the Sun, it is Mercury. The same safety precautions apply. Never look directly at the Sun without protection, especially with a telescope. If you still have eclipse glasses from 2017, they’ll work great. Be sure to check them for damage and don't use if there are scratches or even small pinholes.

Mercury passes between us and the Sun pretty often. Its path around the Sun is much shorter than Earth’s. A year on Mercury lasts only 88 days.

Like a speedy car on the inner lane of a racetrack, Mercury laps Earth about 7 to 8 times each year. So why doesn’t Mercury transit the Sun 7 or 8 times each year? The answer is the same as why don’t we see a solar eclipses each month: the orbit of the planets, Mercury and Venus included, as well as the orbit of the Moon, are a little tilted.

Halley used the fact that each transit looks a little different to observers spread widely across the Earth. Each observer measured the times the transit started and stopped from their location. Using the principles of parallax, this information can be used to triangulate the distance to the Sun with a little high-school-level geometry.

The Morehead Planetarium in Chapel Hill is hosting a viewing event from 11:00 a.m. Monday through the end of the transit just after 1:00 p.m. Volunteers from local astronomy clubs will have solar telescopes available to provide a closeup view. Weather should be good. Skies are expected to be mostly clear for the start with only a slight increase in cloudiness through the early afternoon. There are also several online sources you can see the transit through solar telescopes including one from the Royal Observatory in Greenwich England.

Related Topics

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.