NC schools lag in hiring school psychologists, as mental health needs and special education disparities persist

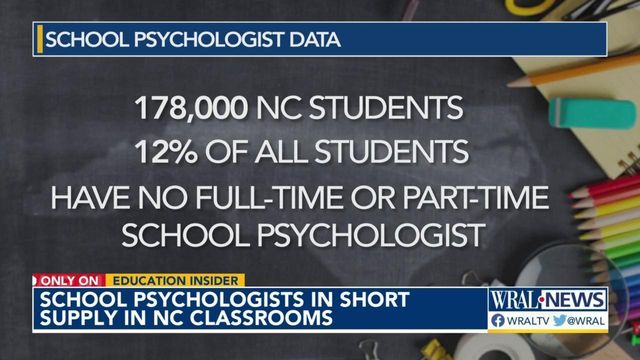

About 178,000 North Carolina children, including tens of thousands who likely have individualized education plans like Kate's, attend a public school in which a school psychologist isn't available even part-time. That's almost one in eight of the state's nearly 1.5 million public school children.

Posted — UpdatedThat’s a relatively common problem, but nobody knew Kate had it, too — yet.

During Kate’s second grade year, Carrboro Elementary school psychologist Jennifer DiGiovanna assessed Kate and figured it out.

Since then, Kate’s teachers have helped her decode words. She works on reading in small groups. She has testing accommodations that allow her to read aloud, take them in a smaller setting, and take more breaks than typically allowed.

Now wrapping up fifth grade at Carrboro Elementary School, Kate’s ability to read has been incrementally closing in on matching her ability to comprehend stories.

“It’s been way more easier, because I can get help, so I understand more what I’m supposed to be doing,” Kate said. Teachers understand what she needs, she said.

Kate’s mom, Karen Herpel, has seen differences in Kate’s school performance and attitude.

“Her confidence has improved each year, and I think that goes a long way for a student,” Herpel said.

Kate’s experience is more common in more populous areas, a WRAL data analysis shows. In North Carolina, dozens of school districts and charter schools have no school psychologist, no in-house expert in identifying special education needs.

About 178,000 North Carolina children, including tens of thousands who likely have individualized education plans like Kate’s, attend a public school in which a school psychologist isn’t available even part-time. That’s almost one in eight of the state’s nearly 1.5 million public school children.

School psychologists, if they are not burdened with special education duties, can train teachers to recognize problems children might be having, help conceive of and run intervention programs to prevent behavior problems, and help students going through tough times. Schools say they are even more of a priority now that COVID-19 has caused students and their families so much psychological and economic distress and as research shows the state falls short in providing mental health care to youth.

North Carolina schools are collectively short more than a thousand school psychologists. To meet national recommendations of 500 students to 700 students per school psychologist, North Carolina would need to triple or quadruple its number of school psychologists, from 770 school psychologists to between 2,110 and 2,954.

Educators and school psychologists trace North Carolina’s shortage back to money: The state doesn’t fund enough positions or pay enough for positions that are funded, and state universities don’t have enough faculty to enroll more school psychology students.

But they argue increasing the number of school psychologists should be a priority, because of the role school psychologists play in helping some of the state’s most vulnerable students academically and in addressing growing mental health needs among children during and resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Having a school psychologist and an effective individualized education plan helped Kate learn. Her mother, a former teacher, fears she might not have otherwise.

“I think that probably really ascertaining what was going on would have taken a lot longer and maybe not have happened at all,” Herpel said. “And that really would have been a detriment to her learning and her progress.“

North Carolina has one school psychologist for every about 1,900 students. Statewide, about 13% of students are in special education. That means the state has one school psychologist for every about 250 special education students — the students who need school psychologists to help oversee their individualized education plans.

But 25 public school districts and 170 public charter schools have no school psychologists at all.

School psychologists are sparse in the state’s westernmost and easternmost counties; an 11-county region across the north and northeast part of the state has no school psychologists and most of those districts’ neighbors have only one.

But the shortage is not only because schools don’t have openings. Some do.

“We had posted a position,” said Stan Winborne, an assistant superintendent and spokesman for Granville County Public Schools. “It was posted for over nine months and we did not get a single applicant.”

The Tar Heel State has more openings for school psychologists than it does people wanting to fill them. Only about 50 students graduate each year from North Carolina universities’ five time-intensive school psychology programs, most of them from the four Master’s degree programs.

That’s half the 100 open psychologist positions currently advertised.

And many of the graduates will enter academia or leave to practice in another state, where schools often pay better.

North Carolina’s maximum pay of about $64,000 for a school psychologist is far less than the average pay for one nationwide, about $81,000. Psychologist pay can top six figures in other health care settings.

Winborne’s rural school district can bring in a clinical psychologist from not too far away, when needed, but that means the district doesn’t have a psychologist on campus as often as they want one.

“They’re simply available, if they’re on staff,” Winborne said. “Our plan was, if we could hire one, not only could they directly serve children and their families, but they could also provide professional development for teachers.”

School psychologists who are fully utilized, such as by offering teacher training and other support beyond psychological evaluations, provide services that can’t be reimbursed by insurance, said Melissa Mascari, the North Carolina School Psychologists Association legislative and public policy co-chair.

Having a school psychologist isn’t just about assessment but also prevention of students’ struggles, Mascari said.

“Our school districts need school psychologists,” she said. “Our schools want them, parents want them.”

Students’ mental health is a major issue for the district, Winborne said, especially when students in the rural district had to learn remotely. Some still have chosen that.

“When they learn virtually, they experience a lot of isolation,” Winborne said. “Many of our families don’t have reliable Internet access so they aren’t able to participate in Zoom or video conferencing activities, and they’re relying almost entirely on the exchange of paper packets.”

That’s why teachers’ and other school employees’ porch visits to students’ homes, often to deliver paper packets, has been so critical this year, giving children more interaction.

Students struggled this year, losing a lot of what schools provide them to stay well and succeed, said Dr. Gary Maslow, a Duke University associate professor and co-director of Duke’s Division of Child and Family Mental Health & Developmental Neuroscience. Routine disruption compounds that problem.

“Kids do best with structure and predictability and this has been a year without structure and predictability,” he said.

Experts contend children’s mental health needs have long been untreated.

And research shows children’s mental health needs are higher than a decade ago.

In North Carolina, and nationally, a greater share of children are reporting feeling hopeless, contemplating suicide and feeling unsafe at school or on their way to it than a decade ago, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Suicides have risen, CDC data show.

And Mental Health America called North Carolina one of the worst states in the country for taking care of children’s mental health.

The organization ranked North Carolina 45 among the 50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C., in part for its relatively high rate of youth with a severe major depressive episode (12.6%, or about 25,000 children) and the proportion of them who ended up receiving some consistent treatment (21.9%, or about about 21,000 children). Most — about 60% — received no mental health care at all.

The state also has a higher percentage of children with private insurance that doesn’t cover mental or emotional issues, the organization found.

But the one metric that North Carolina performed the worst in, compared to other states: The percentage of children with an individualized education plan under the “emotional disturbance” category of special education. That category is meant for students who have a mental health issue that is interfering with their ability to learn.

North Carolina’s rate (3.72 students in that category per 1,000 students) during the latest year of data, the 2017-18 school year, is half the national average (7.57). That means North Carolina identified 5,275 students for special education under the emotional disturbance category but would have identified more than 10,000 if it operated on par with most states.

Understanding specifically what a student’s need is, based on the special education diagnosis and category, drives the student’s intervention plans.

Not having a school psychologist can place children in the wrong categories or not identify them for special education at all, experts say.

In North Carolina and elsewhere, students of color are often over-identified in certain categories, compared to white students, DPI data show. English-language learners are also over-identified in several categories, including for hearing impairment.

Not having the right identification means a student risks not having the right supports for their disability.

That makes having school psychologists with ample capacity to assess students and help oversee individualized education plans, among other things, critical to ensuring all students’ success, advocates say.

“When you don’t have enough school psychologists… there are kids in the buildings who just won’t be seen,” said Kelly Vaillancourt Strobach, policy and advocacy director at the National Association of School Psychologists.

Special attention at an early age made a big difference for Melynda Bryson’s son, Ethan.

Ethan was born only 24 weeks into Bryson’s pregnancy.

His short time growing before his birth has led to years of continuing struggles to develop and seizures.

After his extended hospital stay, he went through the North Carolina Infant-Toddler Program and then into pre-kindergarten, where he first received special education.

Since then, the Carrboro Elementary student’s intervention plans have adjusted and diagnoses have evolved as DiGiovanna has been involved.

Ethan now has occupational therapy and testing accommodations; he tests in small groups to mitigate his testing anxiety. He’s graduated from speech therapy and physical therapy.

As Ethan got older, DiGiovanna noticed his restless behavior — which others had thought could be attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or another intellectual or developmental disability — stemmed from anxiety.

So he got accommodations for that, particularly to help him with test anxiety.

“Without her, he wouldn’t have had that diagnosis and probably would still be having those challenges in the classroom,” Bryson said.

A Duke University study completed last year, and accepted into the International Society for Autism Research journal in February, shows identification disparities among the state’s school districts correlate with whether a district has a school psychologist.

Urban school districts — likelier to have a school psychologist or access to more psychologists — identified a greater share of their special education students as autistic and a smaller share as having an intellectual disability. Rural districts — less likely to have a school psychologist — identified a greater share of special education students as having intellectual disabilities and a smaller share as having autism.

“These findings collectively suggest that in North Carolina primary educational classification of ASD [autism spectrum disorder] and ID [intellectual disability] may be impacted by county of residence, race/ethnicity, and access to economic and professional resources,” researchers wrote.

“ASD diagnostic and treatment services are among the most expensive services of those deployed to support children with neurodevelopmental disabilities and rural schools in the U.S. are often underfunded and have limited access to professional development opportunities…” researchers wrote. “These two facts in combination may result in less well developed ASD services in schools in rural communities.”

The challenge of offering competitive pay for hiring more school psychologists is compounded by a lack of graduates from North Carolina universities’ school psychology programs.

To keep in line with state and national standards, the programs are time intensive and supervision intensive. They take three or more years of going to school full-time to graduate from them, and faculty can only supervise a limited number of students at a time.

Students put in 1,200 hours of training at the Master’s and doctoral levels, in addition to their schoolwork.

That makes the programs relatively expensive to operate, in terms of personnel, faculty say. (That’s on top of the expense of resources for learning, which can also add up quickly. As an example, IQ test kits — which students practice administering — can cost up to $1,500 each.)

Appalachian State University’s Master’s degree program requires five faculty members for just 30 students.

The University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill was only able to accept a handful of new students into its doctoral program this year, out of 120 applicants.

Letanya Love was already working as a psychologist when she decided to transition into school psychology. For a PhD and a year of research, that meant another six years in graduate school full-time, on top of the Master’s degree in clinical psychology she’d already received from North Carolina Central University.

It was worth it to her, she said. She was able to keep working part-time for the state prison system before becoming a teaching assistant and then a researcher.

She was motivated by the difference she thought she could make working in schools, after working as a prison psychologist for 10 years.

“It was really that work that led me to school psychology, because one of the emerging trends I saw within the inmate population was a history of academic and behavioral problems that were not adequately addressed early on,” Love said. “I felt like, had some of these challenges been addressed early on, some of these men could have possibly avoided their interaction with the prison system.”

Now, she sees the need for school psychologists to help children and families deal with the loss and trauma they’ve experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Love graduated with her PhD last August and didn’t struggle to find a job, having had a paid, American Psychological Association-accredited internship in Guilford County Schools. She was able to get a job with a significant local salary supplement and move closer to her family, who reside in Gastonia.

She earns more now than she did in the prison system, but she knows the pay in North Carolina is low.

“While we are being utilized as front-line persons to care for kids in school buildings or online, our compensation needs to match the importance of that work that we do,” she said.

North Carolina’s maximum pay for a school psychologist is far less than the average pay for one nationwide, and it’s far less than what clinics and hospitals pay for psychologists.

The federal Bureau of Labor Statistics last year reported the mean salary for a clinical, counseling and school psychologists is $89,290. Mean salary for those working in schools is $80,960.

Here in North Carolina, a Master’s-level school psychologist maxes out their salary after 25 years, at $61,490, and a Doctoral-level school psychologist maxes out their salary after 25 years, at $64,020. For those just starting out, the state will pay $44,000 annually to a Master’s level school psychologist and $46,530 annually to a Doctoral-level school psychologist.

Districts often offer local supplements to attract candidates.

Average school psychologist salary in North Carolina is $62,332, placing it 38th in the nation and behind several other southern states, according to DPI research. The Tar Heel State’s average salary trails all of its neighbors by a few to several thousand dollars, except for South Carolina, which has an average salary of $52,200. Still, DPI officials note that Virginia and South Carolina school districts set their own pay, so pay can vary quite a bit in those states.

“We hear from many of our bordering districts that they lose school psychologist applicants that take jobs in bordering SC and VA school districts due to higher salaries in the bordering districts,” the DPI salary report reads.

Several superintendents, in a separate survey, said they struggled to hire school psychologists even when they had the money to do so or that they struggled because their rural district couldn’t match the salary supplement provided by a larger, urban district.

Pay was a big reason former North Carolina school psychologists left their jobs, they told DPI in a different survey.

North Carolina has 162 people with school psychology licenses who don’t work in schools and who aren’t retired, according to the December 2020 survey.

The North Carolina Department of Public Instruction surveyed the 281 license-holders not working in schools, asking open-ended questions and allowing narrative responses. DPI received responses from 209 people, 164 of whom said they had worked in schools at one time. Of the 162 who aren’t retired, the plurality — 48 — said they left because of law pay. Another 45 reported moving out of state or switching roles, and many of them specified compensation and caseload as their reasons for moving away or switching roles. Respondents could list multiple reasons.

Narrative responses indicate that higher pay in other states was a factor in people either moving out of the state or traveling across state lines to work in a school setting. Many felt overworked, underpaid and underappreciated.

One psychologist, who lives on the Cherokee Indian reservation, said she planned to return to work when her children were older and commute to Georgia where the pay is “A LOT better.”

Another, who moved to North Carolina from out of state, wrote that they didn’t seek employment in a public school when they moved because the salary they were offered was a “significant decrease” from their prior job. Their prior job was also full-time at one elementary school, which they admitted was a “luxury.”

But that job “allowed me greater flexibility and opportunity with services I could provide which I loved and found so rewarding. My understanding in my area of NC is that the ratios are off and many psychologists are stretched thin between multiple schools, which does not appeal to me. If I were return to the public school setting, I may first consider South Carolina as the districts are smaller and the salaries are higher.”

After conducting the survey, DPI officials came out recommending paying school psychologists more, in an effort to hire more and retain them.

DPI’s budget proposal calls for $10,000 more annually and providing nearly $3,000 worth of additional benefits (about $10 million), plus a 12% supplement for school psychologists with national board certifications (about $3.9 million). The request also calls for $750,000 to create a recruitment and retention coordinator at DPI and a bonus program, and for $3.5 million for a school psychology internship program.

The North Carolina School Psychology Association has also recommended pay increases of at least $10,000.

The DPI superintendent survey earlier this year asked them what has helped them recruit school psychologists and what hasn’t helped.

Several reported success in hiring former interns in school psychology once they graduated their programs, though not all districts can afford to pay for an internship program and universities often can’t afford to pay teachers to oversee practicum students.

Another superintendent said they thought more people would enter school psychology graduate programs if they were offered virtually, so people could retain their full-time employment while going back to school.

To increase the graduate pipeline, a coordinating group of faculty from the state’s five universities with school psychology programs is contemplating how to make it easier for people to become school psychologists.

One idea being floated, said Jaime Yarbrough, an Appalachian State professor, is to make pathways for people with other degrees that shorten the time it would take them to become school psychologists. For example, if a person had a degree in school counseling, they could take some school psychology classes and do an internship, rather than an entire new degree program.

Stipends could also help students who need to work get through their programs faster, said Steve Knotek, an associate professor and the coordinator for UNC’s school psychology program

The amount of training and education school psychologists need makes sense, Knotek said, because students must study both psychology and education, and they must practice extensively to eventually work with some of the most vulnerable students.

Making retraining easier for current school personnel has worked elsewhere, the National Association of School Psychologists’ Vaillancourt Strobach said.

In Iowa, a university-school district partnership retrains rural school district employees who have committed to continue working in those districts, she said.

But retraining is only one part of it, Vaillancourt Strobach said. More students need to be in school psychology programs, and psychology undergraduates need to know more about it as an option.

Another idea from the collaborative group: Set up another training program at another university.

“All of those ideas require additional funding,” Yarbrough said.

Expanding virtual psychology services could help in some cases, particularly for rural school districts, Maslow, the Duke University professor, said. Remote special education assessments are feasible in some cases, even for younger children. He thinks the use of virtual tools will stick around to help less-resourced schools.

“It does expand the opportunities for access,” Maslow said, and “that’s what this next phase is.”

Ultimately, schools say they want to hire in-house school psychologists.

That will take a handful of different efforts.

North Carolina needs to recruit school psychologists from other states, provide incentives for them to work here and make them want to stay, said North Carolina School Psychologists Association’s Mascari.

Mascari’s organization and DPI have identified six states that graduate more school psychologists than they need, including New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Washington, D.C., on the east cast.

Hiring more school psychologists will also help keep around the ones already working in North Carolina, by reducing their workload and allowing them to do more things, Mascari said. School psychologists want to do faculty training and provide mental health supports, but often don’t have the time to do that, even if that’s part of what they were hired to do, she said.

Schools need to keep their psychologists from feeling overloaded, she said.

“They’re not going to stay if they are,” she said.

The state needs to provide incentives for people to work in North Carolina and increase universities’ capacity to teach and graduate more students from their school psychology programs, Mascari said.

Pay won’t change soon, but school psychologists, academics and state Superintendent Catherine Truitt have expressed their support for getting more school psychologists in schools and increasing pay. They’re feeling more optimistic, as the conversation grows around needing more school psychologists and as the COVID-19 pandemic has raised concerns about children’s mental health.

“It seems like the stars are aligning with DPI, the legislature and districts. They’re really getting the need because of lots of tragic things in recent history,” Knotek said.

The concept of educating the “whole child” — supporting all of a child’s developmental needs as a way of readying them for learning — is catching on, Maslow said, and that’s exciting.

The state has recently added an incentive for North Carolina graduates to stay here: late last year, school psychology students became eligible to have a year of loans forgiven for every year they work here after graduating.

Related Topics

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.