Dolly and Tony Griggs live less than four miles away from the Rev. Pat Chisenhall. Hit the two stop lights just right, and you can make the drive from one side of Angier to the other in about five minutes.

But they didn't meet their son’s father-in-law for the first time until four months after the wedding, when they were 200 miles away from Harnett County.

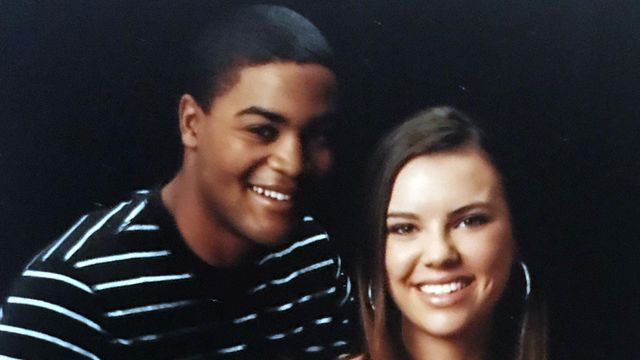

At Fort Jackson, South Carolina, Christian Griggs had spent the last 10 weeks – and half of his new marriage to Katie Chisenhall – in basic training. Now both families were there to watch him graduate.

When Pat Chisenhall and his wife arrived, they were towing a trailer full of their daughter’s things. Griggs’ Army training would take him next to Augusta, Georgia, where he’d continue studying to be a communications operator. And the Chisenhalls came ready for the move.

Griggs wanted to be an officer, and had planned to earn a commission while pursuing his engineering degree. The birth of his and Katie’s daughter Jaden the November before changed those plans. He needed to step up and take care of his family. And he was ready, his father said.

"We sat down and we discussed it, him having an [ROTC] scholarship, a full-ride to N.C. State, that he could go there, get his degree and then come back into the service as an officer," Tony Griggs said. "But he said, 'No Dad. This is my responsibility and I want to take this head on.' So he made the decision to go ahead and forgo his scholarship and to enlist."

Tony Griggs knew a little something about the process. He'd come up in the Army as an enlisted man himself, later becoming a warrant officer. His son knew full well that path could be more physically challenging.

"We sat down and we counted the costs with regard to that," Tony Griggs said. "He fully understood that and was willing to do it. He had no problem coming up the rough side."

Days after Christian Griggs began boot camp in 2009, newly elected President Barack Obama announced that combat operations in Iraq would cease within 18 months. Troop numbers had already declined as the Pentagon began its drawdown.

But Department of Defense figures from the time show that nearly 60,000 U.S. Army troops were deployed in the country, the bulk of America's fighting force there.

And the risks were still real.

In the 10 weeks it took for Griggs to complete basic training, 25 Army soldiers in Iraq had lost their lives.

Jadrin Rhymes was almost a decade older than Christian Griggs and outranked him by a grade or two when they met at Fort Gordon, just outside of Augusta. Griggs struck Rhymes, a specialist, as another hard-working private. They deployed to Iraq together in August 2010.

In close quarters, working 12-hours shifts, Griggs made an impression quickly. He was smart. Serious about his work.

"Whatever we needed him to do, or whatever to handle, he would do it. There were no issues," Rhymes said. "He was all about getting the job done and taking care of soldiers."

Rhymes is a staff sergeant now, with about nine years in the service. He manages about 30 soldiers, and can recognize when they have growing up to do. Griggs wasn't like that. He seemed to know what he was doing and who he was.

"You have some people who join the Army when they're 19 years old, 20 years old, and some people just don't mature as fast," Rhymes said. "They're kids. They're still trying to learn about life and themselves. He joined and really went at it."

Like Griggs, Oskar Castilleja came in at the bottom of the totem pole. That was one of the reasons they stuck together, even when they were deployed. Griggs was a good soldier, a professional. And he was the type of guy people just wanted to be around.

"Anything you needed, he would be there for you," Castilleja said.

In Iraq, there were more convoys than they thought there would be. Those were dangerous, Rhymes said, because you never knew what could happen. Even inside the wire – in the relative safety of the forward operating bases – there were mortar attacks several times a week.

"It was a pretty common deal to get bombed," Castilleja said. "It was something you kind of get used to."

Castilleja never met Griggs' daughter, Jaden. But Griggs talked about her a lot, proudly showed off the photos he kept with him.

"She was his world. She was the reason he served," Castilleja said. "Everything was about her."

He was ambitious and driven, focused on learning and moving up.

"I remember him saying, 'I want to make sergeant here in a few months," Castilleja said. "We were like, 'Nah, dude, that's too quick.’ He was like, 'Watch me.'"

Christian Griggs was about eight months into his deployment in southern Iraq when the truck in front of him turned to fire and shrapnel.

One of the first vehicles in his convoy had hit an improvised explosive device as they traveled outside the wire. Two Army soldiers died from the blast as Christian and his fellow troops took up defensive positions around the remaining trucks.

Jadrin Rhymes was back at the base when he heard the news.

"He was coming back to where we were stationed at, and over the radio, I just heard, 'We got hit! We got hit!" Rhymes said.

Griggs wasn't injured. And the next time Rhymes saw his friend, he seemed OK.

"However he dealt with it, he dealt with it," Rhymes said.

Griggs tried to call his father that night. The line kept cutting out, but Tony Griggs could hear his son’s voice calling to him. Three times it rang, and three times it went dead. Christian Griggs couldn’t fill him in until a day or two later.

Tony Griggs had discussed these scenarios with his son before. Now on the phone, Christian told his father he did everything they'd talked about.

"It was just so impactful just to hear him say how he felt about his friends. Two guys lost their lives that night – and he was pretty close to them in fact," he said. "And just to tell me that he could hear those guys crying for their mom."

Seven years later, talking about that conversation with his son still brings Tony Griggs to tears.

"It definitely impacted him, and I think it gave him a better sense of what it was all about and really matured him," Tony Griggs said. "And he grew up a lot, just realizing just how delicate and precious life really was, and that this was not something to play with and that it was not a game."

On April 29, 2011, Griggs' commanders awarded him an Army Commendation Medal.

His tour in Iraq ended on Aug. 24, 2011.

He had kept in close contact with his family, including his father-in-law, the Rev. Pat Chisenhall, the pastor of the Abundant Life Worship Center back in Angier.

"He was deployed to Iraq, I think it was, and got saved while over there. He told me. He wrote me," Chisenhall said in the deposition. "And upon returning, wanted to be baptized and wanted me to baptize him."

Chisenhall would eventually honor that request, three weeks before he took his son-in-law's life.

Back at Fort Gordon, Christian Griggs attended warrior leadership training at the USA NCO Academy. He received the Army Good Conduct Medal and an Iraq Campaign Medal with a bronze service star.

And he made sergeant, a few months after telling his fellow soldiers he would. He was placed in charge of a team of five soldiers.

"When he made it, it was a surprise, because we didn't know anybody that had ever made it as fast as he did," Oskar Castilleja said. "He just always had that drive to do more, to excel."

But at home, there were signs of strife. Katie and Christian Griggs had bought a place in Harlem, Georgia, while Christian was still overseas. The guys Griggs served with in Iraq visited the house, but don’t remember meeting Katie or their daughter Jaden.

The two were together, then separated. Rhymes said he didn't ask many questions at the time. At least not like he does now as a staff sergeant with his own soldiers, where he gets in the weeds in his role as a leader and mentor.

"To me, they were just a really young couple," Rhymes said. "They just didn't see eye to eye on things. I really didn't get into the details on what they were arguing about and stuff."

But things had gotten worse.

Just after midnight on May 19, 2012, Harlem police went to the couple's home after Katie called 911 and said her husband had locked himself in a bedroom with a weapon. Katie, who declined to be interviewed for this story, reported it as a possible suicide attempt.

"Griggs stated he had the weapon out to scare his wife and had no other intention to use it in any other manner," an officer wrote in the police report. "After speaking with Mr. Griggs, he expressed he had been depressed after coming back from overseas and was battling an addiction problem as well as separation from his wife."

Officers noted Griggs remained calm during the incident, and they took no further action. They did, however, take the gun for safekeeping.

It was sometime around then that Katie left to move back in with her parents in Angier, taking Jaden with her. But she was back more than a month later, when officers arrived at the house to return her husband's weapon.

He was at work, so he retrieved the Ruger from the Harlem police station himself later.

"Mr. Griggs stated that he has been in counseling since the incident and that everything has gotten better," the officer wrote, "also that type of incident will not happen again."

Christian Griggs' Army career ended on July 30, 2012, when he was demoted two ranks to specialist and discharged, three and a half years after he joined.

He told his parents he’d simply decided to get out. They didn't find out what happened until later.

Before he ever deployed to Iraq, he’d failed a urine test. Marijuana, Tony and Dolly Griggs said. Yet the service sent him overseas for a year anyway, and he spent almost another year moving up the ranks before they cut him loose.

"They were just kicking people out left and right, pretty much for any little thing," said Castilleja, who suddenly saw colleagues ejected for violations like drugs or prior misconduct. "Before it was a slap on the wrist. But once you got back from deployment, it's pretty much like, 'Oh, we're done with you.'"

Griggs looked for a bright side, his Army colleagues said. He could see his daughter more. He enrolled in classes at Augusta Technical College, studying to be an X-ray technician. He appealed his discharge and demotion to the Army review board.

To Jadrin Rhymes, it seemed like a speed bump in the road for a soldier he had come to respect and admire.

"You could put Griggs on the street homeless tomorrow and he would work his way out of it," Rhymes said. "That was the type of guy he was."

The Army Discharge Review Board did take up Griggs' case. They stood behind the discharge itself, but found that the Army's characterization of his service "was too harsh and as a result is now inequitable."

The board pointed to the quality of Griggs' performance, his Army Commendation Medal and the length of time between his positive drug test and his ultimate separation.

"Accordingly, the Board voted to grant relief in the form of an upgrade of the characterization of service to honorable," the board’s letter read.

It arrived seven months after Tony Griggs found his son dying on Pat Chisenhall's front porch.

Christian Griggs' return to North Carolina in the fall of 2012 got off to a bad start.

Although separated from her husband in Georgia by almost 300 miles, Katie called the Harlem police on Sept. 24, 2012, to report another suicide threat. When officers arrived at the Griggses’ house, Christian said he had been asleep on the couch and hadn't talked to his wife in several hours.

He told officers the separation was "a little hard on him," but they wrote in their report that he appeared OK and made no references to harming himself. They took no further action.

The next day, Katie called 911 again, this time from her father's home in Angier. She told the dispatcher that her husband was in the yard arguing over custody of their daughter and refusing to leave.

The dispatcher noted that no one was in immediate danger, and although the Harnett County Sheriff's Office responded to the scene, deputies didn't write a report.

Referencing the incident in his deposition, Pat Chisenhall said his son-in-law agreed to leave after authorities talked with him. He couldn't remember what the argument was about.

"And he just was angry towards me, you know, didn't want me to, you know, interject anything or have anything to say," he said during his testimony.

Chisenhall described the incident as verbally abusive, but said he didn't recall any other previous instances of verbal or physical abuse from Christian.

Christian and Katie spent the following months breaking up and reuniting.

In Pat Chisenhall's view, the couple seemed to protect their daughter from the turmoil.

"She was remarkably shielded from all of the – the hostility and the upheaval," Chisenhall said.

Katie and Christian Griggs moved in together again, living in an old house on the Chisenhall property, right next door to Katie's mother and father. Christian got a job. He worked to renovate the space, ripping up bathroom tile, installing flooring and replacing appliances with the help of his father and longtime friends like Brad Buske.

"I could see the frustration starting to build a little bit as he did more to the house and as they started living in it, as they started their life," Buske said. "You could see kind of early on, it just wasn't going as he had hoped, or as he wanted it to, really."

Friends and family say he was growing increasingly frustrated with his access to Jaden as his relationship with Katie faltered.

Several months before Griggs died, Pat Chisenhall said in his 2016 deposition, his son-in-law had come to the house "hostile, irate" when Katie wouldn’t let him in.

Chisenhall followed when he saw him go into the nearby woods, where he found Griggs sitting against a tree with photos of Jaden and Katie spread on the ground next to a handgun.

“And he was extremely despondent, depressed. And I asked him was he suicidal, and he said yes, and talking about taking them and himself together,” Chisenhall said in the deposition. “And it was very alarming. It was very upsetting to me.”

The pastor said he talked his son-in-law into handing over the gun, but said he refused offers to get him psychiatric counseling.

Chisenhall didn’t call the police. He told lawyers in the deposition he later let Christian move back in with his daughter and granddaughter. He said he only told his wife what he saw.

Several weeks later, at his son-in-law’s request, Chisenhall returned the gun.

Tony and Dolly Griggs knew nothing about the claims of suicide threats or 911 calls – in Georgia or in Angier. Christian hadn't told them, nor had Katie or her father, who at one point considered himself Christian's spiritual adviser.

"No one mentioned it to us. When Christian came home, he didn't show any signs he had any issues like that," Dolly Griggs said. "I know that the biggest thing he said to us was that he wanted to be there for his daughter, and that was always first and foremost that was on his mind."

They remember the simple things. Jaden napping on Christian’s belly. The two of them coloring together on the bed. The way she called for him in the middle of the night when she stayed with them.

"She loved her father," Dolly Griggs said.

His sister Krystle Miller, four years Christian's junior, remembers meeting him at a Garner sports bar sometime in 2013. She was home from college at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington and he was living just outside Raleigh, enrolled again at North Carolina State University and excited about the prospect of being back at school.

But tears welled in his eyes when he talked about not being able to see Jaden when he wanted. He and Katie had agreed he would have custody of his daughter every other weekend, but he told his sister he felt like he had to jump through hoops to spend time with her.

"He said it's like the most stressful thing he's ever dealt with," Krystle said. "I was like, 'I can only imagine.'"

September 2013 was a period marked by highs and lows.

Pat Chisenhall baptized Christian Griggs in the reverend's backyard swimming pool, but Christian also called his father from Katie's house around 2 a.m. one night saying he needed a place to stay. Katie had kicked him out, Christian told his parents, throwing his phone and clothes in the woods.

But Griggs also had things to look forward to.

His fall break from N.C. State was approaching, and his grandmother would be visiting from Detroit. Griggs was scheduled to have custody of Jaden that weekend, so he was thrilled the two would meet for the first time.

On his whiteboard calendar, that Saturday – Oct. 12, 2013 – was marked and underlined with his nickname for his daughter: "JJ." He drove in from Raleigh that Friday night.

Much of what happened next remains in dispute.

Pat Chisenhall wasn't there. In his deposition, he recounted what his daughter told him: that Griggs was upset that she had taken Jaden to the zoo with her friends. That he had pulled the AC unit out of the window to get into the locked house.

"And I don't know about threats and those type things, but it was extremely upsetting to her," Chisenhall said in the deposition.

It was dark when Christian Griggs arrived at his parents’ house that Friday night, they said. Aside from Jaden's absence, there didn't seem to be anything wrong with their son.

"The first thing I said to Christian when he walked through the door – I said, 'Where is Jaden?'" Dolly Griggs said. "He just kind of smiled and I kind of knew that he must have had issues with Katie, so I didn't push it."

He didn't provide any details about what happened. He sat down with his grandmother and they talked and laughed. He told her about school. His demeanor that night makes them doubt the Katie's story.

"My mom referred back to him and said, 'We don't say, bye. We say, see you later," Tony Griggs remembers. "He said, 'All right, granny. I'll see you later.'"

Christian told his sister he was a little stressed, as he often was, about getting access to Jaden that weekend. But said he'd figure it out.

"I was like, 'OK,' and he gave me a hug and told me he loved me," Krystle said. "And that was one of the last conversations we had."

Sometime that evening, Oct. 11, 2013, Pat Chisenhall and Katie Griggs went to the Harnett County courthouse complex in Lillington and swore out warrants against Christian Griggs.

Pat Chisenhall seemed unclear on the details he received from the magistrate's office.

"My understanding was that a restraining order was taken out, but he also told us we needed to go to Raleigh the next morning and do the same thing there," he said in the deposition. "Don't know why."

Chisenhall and his daughter planned to follow those instructions the next day, traveling to Raleigh in the morning.

Advocates for victims of domestic violence say this kind of confusion isn't terribly unusual. Attorney Amily McCool spent four years as a Wake County prosecutor before working domestic violence cases in civil court. She said victims can legally file domestic violence protection orders anywhere in the state, so there wasn't really a reason to go to Wake County. But court officials don't always provide correct information.

"Folks who are just trying to navigate the systems oftentimes do not understand, and have not had someone taking the time to explain it to them," she said.

But there was no restraining order, no domestic violence protection order, just two unserved misdemeanor warrants for Christian Griggs' arrest. There's no evidence he knew anything about them.

That night, after leaving his parents' house, Griggs rang his wife's phone number from his cell nearly two dozen times.

She didn't call back.

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.