UNC researchers say much of oil spill floating under Gulf

UNC researchers say the amount of oil spewing from a wellhead beneath the Gulf of Mexico is much more than official estimates, and much of the oil is trapped undersea.

Posted — UpdatedRichard McLaughlin, a mathematics professor, said he and his colleagues estimated the British Petroleum well is spilling about 56,000 barrels of oil a day into the sea, which is more than 10 times BP's estimate of 5,000 barrels a day. The UNC estimate is based on the geometry of the broken drilling pipe and the speed of the oil flow seen in underwater video, McLaughlin said.

"It’s just a back-of-the-envelope calculation, but I think that we are fairly confident that more is coming out than the 5,000-barrel estimate," he said.

BP's estimate is based on the amount of oil floating on the surface of the Gulf of Mexico, but McLaughlin and mathematics professor Roberto Camassa said much of the oil is trapped far underwater, where it is spreading out in plumes.

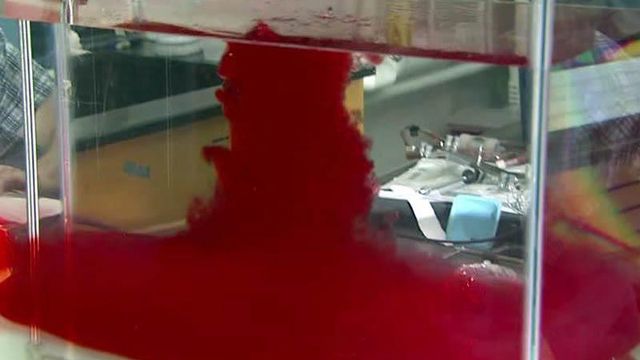

The researchers have run simulations in a tank on the Chapel Hill campus that is filled partly with saltwater and partly with freshwater to mimic the denser deep-sea waters and the warmer, lighter water closer to the surface. In their experiments, they spray dyed alcohol, representing the oil, from a nozzle at the bottom of tank and have found that the alcohol spreads out about halfway up the tank and doesn't make it to the top.

The speed at which the oil is gushing from the wellhead is part of the reason its creating underwater plumes, Camassa said.

"(The oil) might not make it all the way to the top, basically, because it encounters some warm layer of water, which is (lighter),” he said. "If you were to release the oil at a much lower speed, it would just make bubbles of oil (that would float to the top)."

McLaughlin said it's difficult to predict what will happen to the "trapped cloud" of oil below the surface.

"There's some uncertainty there, for sure," he said.

John Bane, a professor of marine sciences at UNC, said the movement of deep-sea currents make it hard to say where the oil could end up. Also, the oil is breaking down in the water, he said, with lighter elements eventually floating to the top and evaporating or dispersing and tar-like elements becoming heavier and sinking to the bottom.

Bane said some of the oil could follow the Gulf Stream current and affect the North Carolina coast, but he said the impact would be minimal.

"I don’t think the impact on a North Carolina beach would be some giant pool of black crude oil arriving at the beach," he said, noting it likely would take five to seven weeks for any oil to reach the state.

"That gives the oil a lot of time to disperse and degrade some," he said.

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.