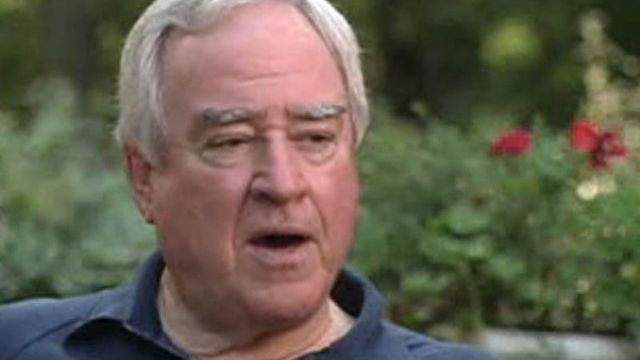

Former N.C. Gov. Bob Scott dies

Former Gov. Bob Scott, who helped consolidate North Carolina's university system as governor and later was president of the state community college system, died Friday. He was 79.

Posted — UpdatedScott died at 3 a.m. at the Hospice Palliative Care Center of Alamance County, his family said. His funeral be at 11 a.m. Tuesday at Hawfields Presbyterian Church in Mebane.

“Gov. Scott devoted his life to public service," Gov. Beverly Perdue said in a statement. "He always believed that North Carolina could be a better place, with wider doors of opportunity for all our people, and he worked to make it so."

Perdue ordered all North Carolina state flags be flown at half-staff until sunset Tuesday in honor of Scott.

Scott was the third generation of an Alamance County farming family to hold state office. His grandfather, R.W. Scott, served in the House and Senate, and his father, Kerr Scott, was elected governor in 1948 and was named a U.S. senator in 1954.

"Politics has sort of always been in our family," Bob Scott once said.

The youngest of three children, Bob Scott grew up on the family's dairy farm, attended Duke University and graduated from North Carolina State University with a degree in animal industry. A year after graduation, he was drafted and served with the Army Counter-Intelligence Corps in Japan.

"I always felt that I was fortunate to be born and spend my early youth during the period of time that I did because I was able to see and participate and be a part of the pre-mechanical age of agriculture," he said in a 1986 interview.

Scott's rise in state politics sprang as much from his farming background as his well-known family name. He and his wife, Jessie Rae, were named one of five outstanding young couples in 1959 by the National Grange, an agricultural group, and he was elected master of the North Carolina Grange two years later.

That position, along with his role as chairman of THE advocacy group United Forces for Education, provided insight into agricultural and education needs statewide and put him in touch with people across North Carolina.

Still, he said he had no intention of seeking public office until he saw a newspaper story in 1963 naming him as a possible candidate for governor.

"If someone had told me a year or 18 months before I ran for lieutenant governor that I would be involved in and seeking public office, I would have laughed out loud," he later said. "I really did consider myself as having a career in agriculture and looking after the farming operation. I was happy doing that and enjoyed it."

Instead of governor, he decided to run for lieutenant governor and won the office in 1964. Four years later, he followed in his father's footsteps and was elected governor.

Scott's gubernatorial term was marked by public opposition to school integration and to the Vietnam War, and he sometimes had to use state troopers or members of the National Guard to maintain order. A staunch advocate for civil rights, he appointed Sammie Chess Jr. as the first African-American to serve as a superior court judge.

"I think the great story of North Carolina during the period of the early 1960s on through 1971 and (1972) is what did not happen in North Carolina," he said. "We had some racial tensions. We had some burnings. We had to call out the National Guard a few times ... (but) nothing really bad – of a holocaust type thing that some other states incurred."

His rural roots allowed him to connect with average citizens despite his family's pedigree. He often remarked he was just as comfortable eating with "barbecue kings" as he was with European royalty. In fact, he and his wife hosted the executive mansion's first documented black-tie possum dinner in 1969.

"They'd sit together as friends, and they'd put on black tie and eat possum and yams and persimmon pudding," said Rob Christensen, a political columnist with The News & Observer newspaper in Raleigh. "He just had that sense of humor that he may be governor, but he's not going to be a stuffed shirt."

Martin Lancaster, who ran Scott's lieutenant governor campaign and later followed him as community college system president, said Scott had a smile and a story to tell everyone he met.

"He could put on a sport shirt and eat chitlins with the best of them and then go take a shower and put on a white shirt and sit down with the CEO of the largest corporation in the state," Lancaster said.

As governor, he also oversaw the creation of the 16-campus University of North Carolina system. The system previously included campuses in Chapel Hill, Raleigh, Greensboro, Wilmington and Asheville. He appointed a commission to study the issues involved in adding various campuses and to decide which schools would become part of the consolidated system.

Scott also pushed for education at the other end of the spectrum, creating a pilot kindergarten program and successfully lobbying for North Carolina's first cigarette tax to help pave the way for public school kindergarten statewide.

His passion for history led to the preservation of the State Capitol, restoration of the Governor's Mansion, creation of the Reed Gold Mine State Historic Site and other contributions to North Carolina art, culture and history.

He was unsuccessful in his efforts to amend state law to allow governors to serve a second term, and he left office in 1973. After the General Assembly approved the measure several years later, Scott took another run at the governor's office but was defeated in the Democratic primary by incumbent Gov. Jim Hunt.

Ironically, Scott helped launch Hunt's political career years earlier.

"When Bob Scott was governor, he appointed Jim Hunt to chair a (Democratic) Party commission that opened up the party back in the late '60s to minorities and women and young people," Democratic strategist Gary Pearce said. "In a lot of ways, that gave Jim Hunt a jump-start on his political career."

Scott served in a variety of positions after his term as governor, including as a member of the state Agribusiness Council, co-chairman of the Appalachian Regional Commission and partner in a Raleigh lobbying firm.

In 1983, he was named president of the North Carolina Community College System. During his 11-year tenure, he worked to establish a system of common credits so students could transfer between colleges and could apply their credits toward degrees from four-year universities.

"It served as a model for systems all over the country," he once said of North Carolina's community colleges. "I was involved in the program in 1969 when I was elected governor and really before that as lieutenant governor, when I was a member of the state board of community colleges."

Lancaster said Scott enjoyed overseeing the community colleges more than being governor.

"I think Gov. Scott thought he could have impact on lives more directly through the community colleges than he did as governor," he said. "He was the person who, though his roots were rural, reorganized the university system for the 21st century."

Scott's daughter, Meg Scott Phipps, continued the family's political tradition by winning the state agriculture commissioner race in 2000. Three years later, she was implicated in a campaign finance scandal that led to her resignation and conviction on public corruption charges – a turn of events that devastated her father.

Scott is survived by his wife, Jessie Rae Scott; daughters Meg Phipps, Mary Scott, Susan Sutton and Jan Scott; seven grandchildren; and his sister, Mary Kerr Lowdermilk.

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.