Money chase continues for NC lawmakers through Election Day

Candidates have to chase dollars even as they chase votes this fall, as they brace for an election year made all the more expensive by non-candidate spending. Meanwhile, voters and watchdogs find themselves without hard data to show who is giving until late October.

Posted — Updated"It's ridiculous the amount of money that a candidate has to raise," said Kim Hanchette, a Democrat running for the Raleigh-area state House seat once held by Rep. Jim Fulgham, R-Wake. "You're mostly fundraising instead of what you should be doing, which is getting smart on the issues and talking to voters."

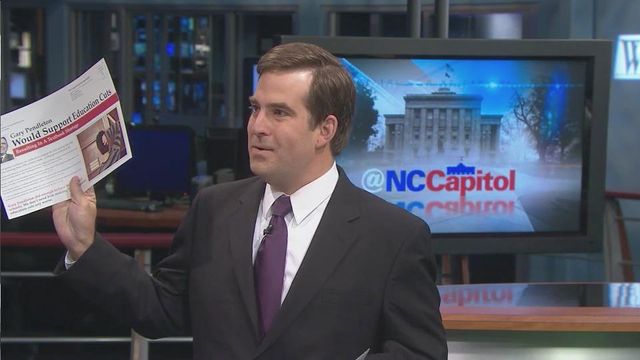

Hanchette, a diabetes educator, and Republican Gary Pendleton, a retired general and former Wake County commissioner, have been the subjects of a flurry of direct mail pieces in their district. While the candidates and their parties are responsible for many of these fliers, others mailed on Hanchette's behalf have come from N.C. Families First, a third-party group backing Democrats in several races this year.

"Does it make me mad? No," said Pendleton, whom N.C. Families First hammers for both recent education cuts – on which he didn't have a vote – as well as his work as a county commissioner in the 1990s.

Pendleton predicted the fliers will backfire, brushing them off as untrue. "It just doesn't bother me. It's a shame that people can't be honest."

The involvement of third-party groups like N.C. Families First is not a new trend – court decisions over the past decade have increasingly cleared the way for a variety of nonprofit and political action groups to get involved in the political process. But their involvement not only lards more spending into campaigns, it also prods lawmakers to raise more money in their own rights.

Now, as campaigns kick into high gear to attract voters, both Republicans and Democrats are also still scrambling for campaign dollars. But for the next month, a gap in campaign reporting deadlines means voters won't know for sure who is trying to influence this fall's elections and next year's public policy debates.

Still fundraising

Pretty much every candidate, incumbent or challenger, will tell you that they would rather be on the stump talking to groups or knocking on doors than tied down in fundraisers or dialing for dollars. But in reality, there's no way that an all-grassroots campaign can compete in state House districts that contain 80,000 residents and state Senate districts with roughly 190,000 residents.

That's why Reps. Nathan Ramsey, R-Buncombe, and Jason Saine, R-Lincoln, found themselves meeting with lobbyists and their clients on Wednesday in some borrowed office space on South Glenwood Avenue in Raleigh. Rep. Mitchell Setzer, R-Catawba, was originally supposed to be part of the confab but had a scheduling conflict, according to emails shared with WRAL News by multiple lobbyists invited to the meetings.

"Meeting times will be filled on a first-come, first-served basis. In addition, Representatives Ramsey, Saine, and Setzer will have an event that evening at Tyler's Taproom," read the original invite to the meetings and evening event. That "event" was a fundraiser, aimed at restocking campaign larders.

While Saine is expected to win his heavily Republican district handily, Ramsey finds himself in a tougher re-election bid and the target of third-party television ads accusing him of cutting taxes for wealthy individuals while cutting school funding.

"What we're told by people who run in these circles is the standard fundraiser gets a little boring," Saine said a day in advance of the meetings and fundraiser.

Arranging times to sit down with those who have concerns about issues allows for a serious policy talk, he said, rather than a few cursory ideas exchanged over wine and hors d'oeuvres. "You don't really get to have a conversation."

Asked whether there was any expectation that those who attended the policy sit-downs would attend and contribute during the fundraiser, Saine said, "No, none whatsoever. This is just a way to make use of my time better. Whether or not they give to me, I'm open to them."

Rep. John Bell, R-Wayne, had been scheduled to hold meetings during the day but was not part of the fundraiser. Still, campaign watchdogs said it's hard to tease out where policy discussions end and fundraising begins.

"It specifically links private access to lobby a legislator with political fundraising," said Bob Hall, director of Democracy North Carolina, a good-government watchdog group.

Hall said the approach is "unusual," going beyond the typical few minutes of face time one might get at a party.

"This new approach goes further to market private, individual meetings between a legislator and a client," he said.

By all accounts, Ramsey and Saine are responsive to constituents and well liked – or as well liked as any political incumbent is these days – in their communities. Still, it's not the average voter navigating a driver's license snafu that fills campaign coffers. The names on campaign finance reports are replete with lawyers, builders and advocates whose organizations and interests are well and regularly represented in the Legislative Building.

For example, Saine describes the portfolio of issues that he works on at the General Assembly as "not sexy" issues dealing with computer systems and databases. But he still votes on a range of issues dealing with the regulation of car sales to the regulations governing workers compensation issues and sales taxes. In addition to dozens of small donors from his home district, groups like the Petroleum and Convenience Marketers PAC and the North Carolina Automobile Dealerships Association wrote his campaign $1,000 checks this year.

Even Hanchette, who has never been an elected official, and Pendleton, who was appointed to fill Fulgham's unexpired term after the close of the legislative session, have monetary connections to some of the hottest legislative issues. Planned Parenthood of Central North Carolina PAC, a group that advocates for broader abortion and women's health care access, is among Hanchette's donors. The PAC for Reynolds American, a tobacco company that had an interest in how lawmakers regulated and taxed e-cigarettes this summer, gave to Pendleton.

Those conflations of interests have Hall and other campaign watchdogs calling for greater disclosure for candidates and allied groups who spend on their behalf.

Costs increasing

The pay for a rank-and-file member of the General Assembly is $13,951 per year plus expenses. The job is, in theory, part time, although work on legislative committees, constituent services and legislative sessions that drag on longer than expected often pile up to a full-time gig.

In fact, this summer's longer-than-expected legislative session is one reason candidates like Ramsey and Saine are still fundraising. Ethics rules prohibit members from collecting donations from organizations with lobbyists while the General Assembly is active in Raleigh.

That delay was painful for incumbents in today's environment, when the money spent winning a legislative seat can easily be 10 to 70 times the job's salary.

There was a time when the thought of a $1 million state legislative campaign would have been laughable in North Carolina. But in 2012, spending in the race between now first-term Sen. Chad Barefoot, R-Wake, and then-Sen. Doug Berger, D-Franklin, easily topped that mark. Lawyers and lobbyists, health professionals and real estate interests topped the list of industries donating to legislative candidates that year.

Candidates get help from their parties and fellow candidates. Those with less competitive races, particularly top committee leaders and chamber leadership, can raise excess cash that can then be funneled to less well-known candidates. That kind of intra-party assistance helped Republicans pump cash into races that unseated long-held Democratic majorities in 2010 and then expanded GOP control of the House and the Senate in 2012.

Independent spenders crash the political parties

By contrast, the smallest donation N.C. Families First reported on a recent disclosure statement was $50,000. That came from Dean Debnam, chief executive of the liberal pollster Public Policy Polling. N.C. Families First is the reincarnation of N.C. Citizens for Progress, a Democratic group that spent heavily in the 2012 election, mainly on ads aimed at defeating now-Gov. Pat McCrory. This new version is headed by Jay Reiff, an aide to former Democratic Gov. Mike Easley. Michael Weisel, a lawyer who works for a number of Democratic campaign groups, is Families First's general counsel and treasurer.

Weisel declined to discuss the group's work, beyond saying, "There are large numbers of North Carolina citizens very concerned about adequately educating our state’s children and the current North Carolina General Assembly’s legislative priorities and policies."

He specifically would not divulge the logic behind which races have been or will be targeted. However, the organization has reserved television air time in the Raleigh market for October and reported having at least $1.4 million on hand as of Sept. 18.

Much of that funding has come from three other independent spending groups: Real Facts, N.C. Citizens for Protecting our Schools and N.C. Futures Action Fund, making the trail of which individuals and corporations gave to the campaign efforts in question all the more challenging to follow.

Of course, N.C. Families First won't be the only third-party spender at play in this year's election. Aim Higher Now NC, a group that has its own ties to N.C. Citizens for Protecting Our Schools, is another third-party group backing Democrats that is airing ads in Ramsey's race.

Oddly, there are few Republicans independent-spending groups weighing into the campaign yet. For the past two cycles, GOP candidates have enjoyed an advantage in outside help, and there is still time for Republican backers to weigh in significantly. For example, Real Jobs NC spent more than $700,000 in 2012 boosting GOP candidates and is preparing to wade into legislative campaigns again this year.

"The board has determined to be involved and has made plans to engage in this election cycle and will do so if adequate funding is secured," said Roger Knight, a lawyer and spokesman for Real Jobs.

For candidates, having a third-party spend on your behalf can be a double-edged sword.

"I don't like the negative ads, and honestly, I think it's a turnoff to voters," said Hanchette.

While N.C. Families first is trying to help her by blasting Pendleton, she said voters are worn out by an increasingly negative campaign. "What I'm hearing from voters is a lot of cynicism about the process."

Alexander, the Republican running to replace retiring Sen. Neal Hunt, R-Wake, said many voters have a common response when he introduces himself.

"Most of them say I'm tired of getting your picture in my mailbox," Alexander says with a laugh.

Alexander stepped into the race when Fulgham, who had planned to leave his House seat to run for the Senate, died this summer. That last-minute transition may have made for a closer campaign and attracted additional spending from both parties and independent-spending groups. Asked about the possibility that spending on the race could total $1 million by Nov. 4, Alexander called the idea, "grossly stupid.

"That's just too much money to spend on this thing. I'm not going to raise that kind of money," he said.

Candidates and independent spenders do share one thing in common. State campaign finance rules will keep much of their fundraising and spending under wraps until roughly two weeks before the election.

Flying blind

September and early October are something of a campaign reporting dead zone for state legislative races. Candidates had to report their fundraising and spending through the first half of the year on July 10 but won't have to file their third-quarter reports until Oct. 27. They will have to start filing "48-hour notices" that detail contributions of more than $1,000 starting Oct. 19. By and large, the same rules apply to independent-spending groups that have established committees with the state board of elections.

That means, for example, Ramsey and Saine won't have to report donors who gave during the joint fundraiser that followed the office meetings until Oct. 27. N.C. Families First will also be able to keep any additional money it raised and spent largely under wraps until then as well.

"The election process is a public process, and the public should know how the money is flowing," Hall said.

There are some ways to fill in the gaps. Broadcast television stations, including Capitol Broadcasting's WRAL and Fox 50, have to file reports with the Federal Communications Commission reflecting air time reserved by either politicians or groups airing campaign-like ads, and media tracking services track ads as they air, keeping running totals that show the horse race.

Meanwhile, radio ads, Internet-based advertising and campaign direct mail pieces, like those clogging the mailboxes of voters in hotly contested races, largely go untracked and unreported until the election is nearly over.

"You have to assume the volume of ads in the U.S. Senate race begins to dull the senses," Stewart said.

Related Topics

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.