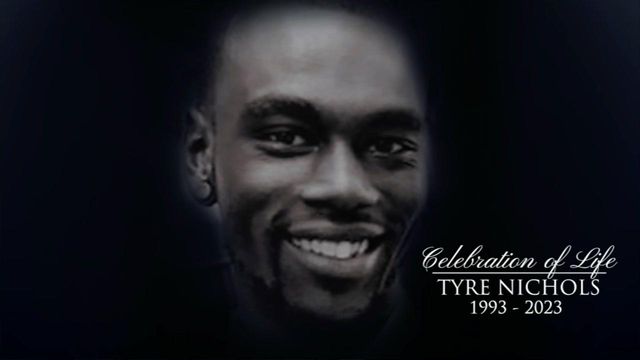

Memphis Gathers in Grief at Tyre Nichols’ Funeral

MEMPHIS, Tenn. — His siblings remembered his passion for skateboarding and his love of photography. They said he had a sense of independence, a comfort and confidence in being himself, that had taken hold at an early age. At 29, Tyre Nichols was finding his way.

Posted — UpdatedMEMPHIS, Tenn. — His siblings remembered his passion for skateboarding and his love of photography. They said he had a sense of independence, a comfort and confidence in being himself, that had taken hold at an early age. At 29, Tyre Nichols was finding his way.

But as his family gathered with hundreds of mourners for his funeral Wednesday, relatives said they were searching for meaning in the killing of Nichols at the hands of Memphis police officers, who pulled him from his car and severely beat him. His mother, RowVaughn Wells, said she was sustained by the idea that her son had been part of a divine mission — “sent here on assignment from God” to change how police operated in Memphis and around the country.

“I guess now his assignment is done,” Wells said from the pulpit at Mississippi Boulevard Christian Church, “and he’s been taken home.”

The essential message from speaker after speaker was that a new mission was beginning, one that would have to be led by the many Americans who were angered and horrified by the nearly one hour of footage that showed Nichols being kicked, pummeled and pepper-sprayed by those officers.

“This is a family that lost their son and their brother through an act of violence at the hands and the feet of people who had been charged with keeping them safe,” Vice President Kamala Harris said at the pulpit. She noted that one vital effort would be renewing efforts to pass federal legislation that would bring increased accountability to cases of police violence.

As a senator, Harris helped author the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which passed in the Democratic-controlled House in 2021 but failed in the Senate. In her remarks, she called on Congress to pass the bill and said that President Joe Biden would sign it, drawing applause from the crowd.

“We will not be denied,” she said. “It is not negotiable.”

The service was in many ways an induction ceremony, officially adding Nichols to a group of Black men and women whose deaths have inspired widespread outrage and activism.

In attendance were Philonise Floyd, the brother of George Floyd, who was killed by a police officer in Minneapolis, and Tamika Palmer, the mother of Breonna Taylor, who was shot to death by police in Louisville, Kentucky. The mother of Eric Garner, who died in New York City, and the sister of Botham Jean, who was gunned down in his own apartment in Dallas, were there, too. Tiffany Rachal, the mother of Jalen Randle, a 29-year-old Black man who was killed by a Houston police officer last year, sang the gospel song “Lord I Will Lift My Eyes to the Hills.”

Their presence was meant to send a signal that Nichols’ death was the latest blow in a lengthy struggle. “These are not isolated incidents,” said Ben Crump, a civil rights lawyer who represents many of these families, including Nichols’. Perhaps, as his mother hoped, his death could be a force for something better.

Nichols died Jan. 10, three days after a traffic stop that turned into a brutal beating by Memphis police officers who were part of a specialized unit formed to help halt a surge of violence in the city.

Video from the officers’ body cameras and a stationary surveillance camera that was released last week showed the assault and Nichols begging for his life. The encounter began as officers approached his vehicle — they claimed he was driving erratically, although the city’s police chief has said no evidence of that has emerged — with guns drawn and pulled him from his car. The officers shouted often-contradictory orders before using pepper spray on Nichols, who ran off.

But officers soon caught up with Nichols and assaulted him, with one officer delivering a series of blows to Nichols’ head while two other officers held his hands behind his back.

Crump noted that within 20 days of his death, five police officers were fired for using excessive force and failing to render aid, and then were charged with second-degree murder, along with other felonies. The Scorpion unit, the specialized group patrolling high-crime areas that the officers had been part of, has been disbanded.

“His legacy will be one of equal justice,” Crump said of Nichols. “It will be the blueprint going forward.” An ice storm had left the roads in Memphis treacherous. The funeral had to be pushed back several hours Wednesday because of the conditions. Even so, people crowded into Mississippi Boulevard Christian Church, a soaring sanctuary in the heart of the city.

“It is good for us to be together in the same space,” said J. Lawrence Turner, the church’s pastor, “and, yes, cry with each other and also find hope that will drive us to hopefully dismantle this culture that normalizes this kind of violence.”

The Rev. Al Sharpton, who delivered the eulogy, sought to connect the death of Nichols to the larger history of Memphis, including the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968.

He noted that King had been in Memphis to support sanitation workers who were on strike, an effort to help Black city workers gain better treatment. And he noted that the five officers charged with Nichols’ death were also Black — a fact that added to the anguish for him and many others.

“The reason why, Mr. and Mrs. Wells, what happened to Tyre is so personal to me,” Sharpton said, referring to Nichols’ stepfather and mother, “is that five Black men that wouldn’t have had a job in the Police Department, would not ever be thought of to be in an elite squad, in the city that Dr. King lost his life, not far away from that balcony — you beat a brother to death.”

Lawyers representing the officers have urged the community not to rush to judgment, saying that the video footage was not entirely conclusive.

As much as the funeral was employed as a call to action, it was also a moment to remember who Nichols was before his name became a rallying cry in protests around the country.

Nichols moved from California to Memphis in 2020 to be closer to his mother. He had a 4-year-old son and was working with his stepfather on the second shift at a FedEx facility in Memphis.

His family said his name had come from “Silverado,” one of his mother’s favorite movies, a Western released in 1985. The sheriff’s deputy was named Tyree.

Keyana Dixon, Nichols’ older sister by 11 years, described taking care of him when he was young, when all he wanted to do was eat cereal and watch cartoons. “I see the world showing him love and fighting for his justice, but all I want is my baby brother back,” she said through tears. “Even in his demise, he was still polite: He asked them to ‘Please stop.’”

His brother Jamal Dupree said Nichols saw the world in a way he did not. He pointed out the photos that Nichols had taken that were displayed during the service. “He set his own path,” Dupree said. “He made his own light.” In the video, Nichols had called out for his mother. “Mom, mom, mom,” he said. Her home was less than 100 yards away.

Sharpton said hearing those calls made him think of his own mother, and how much he had relied on her and turned to her for comfort and safety.

“All he wanted to do was get home,” Sharpton told the congregation. “Home is not just a place. Home is not just a physical location.

Related Topics

Copyright 2024 New York Times News Service. All rights reserved.