How long before things are normal? We don't know.

When life gets back to normal depends on multiple factors, including how effective efforts are to curb transmission.

Posted — UpdatedGovernment officials don't know when life will get back to normal.

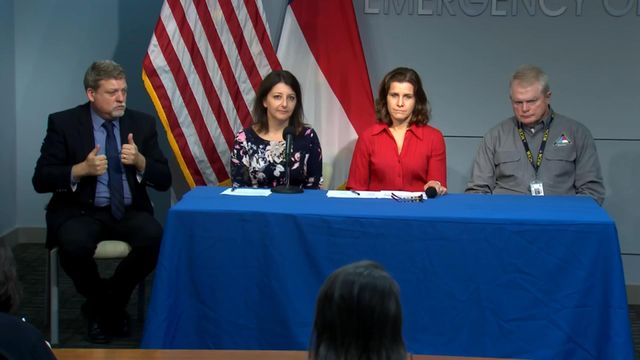

"I don't think that we can know that yet," Dr. Mandy Cohen, North Carolina's secretary of health and human services, said Friday afternoon.

Cohen wouldn't even speculate on whether we're talking months versus weeks.

The answer depends on how effective society's efforts are to mute the virus' spread and on efforts to study the virus itself. After Gov. Roy Cooper called Thursday for people to cancel events expected to draw more than 100 people, his administration said this guidance was meant to last 30 days, with re-evaluation as needed.

The state university system, headed by a former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Dr. Bill Roper, transitions to online classes next week and plans to stay that way indefinitely.

Virginia schools will close for at least two weeks after a Friday edict from that state's governor. North Carolina hasn't called for statewide closures, though a handful of systems made the move themselves this week.

Durham Public Schools, for example, are closed until April 3, using a combination of spring break, teacher workdays and online learning to keep students out.

"In practice, health officials will dial down social distancing when they see a significant decrease in the daily number of cases," Dr. Jonathan Quick, an adjunct professor at the Duke Global Health Institute, said in an email Friday.

"Critical factors in getting to this point are: First, adequate testing so we know the actual number of cases, where they are and whether the number is going up or down," Quick said. "Second, the extent to which people (who are sick) actually self-isolate. Breaking self-isolation and therefore spreading the virus will prolong the pandemic."

Testing is a problem. State and national officials have acknowledged a lack of supplies, though North Carolina officials have been unwilling to put numbers on the difference between the tests they have capacity for versus the number of tests needed. They have said this week that the situation is improving.

The good news is state officials said Friday afternoon that North Carolina has yet to see a "community transmission" of the virus, meaning every known case came from someone who traveled to an area where the virus was prevalent or had contact with another virus patient.

“One is that it’s like the SARS virus in 2003, which within a matter of weeks got to 27 countries, but in six months, it was gone and never returned," Quick said, calling this "the best-case scenario."

"The second scenario would be more like the 1918 flu pandemic, where it gets quiet in the summer and then was back again in the fall," he said. "The third scenario is that it actually doesn’t have much of a seasonal effect. It just keeps on moving along until we get a vaccine.”

That might take six months to a year, or "might be spread over a more manageable several years," he wrote.

"Either way, once the first wave is done, the virus is probably here to stay," Lessler wrote. "This seems scary, as if we are resolving ourselves to tens of thousands – or hundreds of thousands – of deaths in the United States each year. But it is very unlikely that things will remain that bad."

One reason: Some viruses confer immunity, so you only get sick from them once, or at least you don't get as sick with later exposures. But because the coronavirus is new, scientists don't know whether it people will develop a long-lasting immunity to it.

"So there will be a time after the pandemic when life returns to normal," Lessler wrote. "We will get there even if we fail to develop a vaccine, discover new drugs or eliminate the virus through dramatic public health action, though any of these are welcome because they would hasten the end of the crisis."

Related Topics

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.