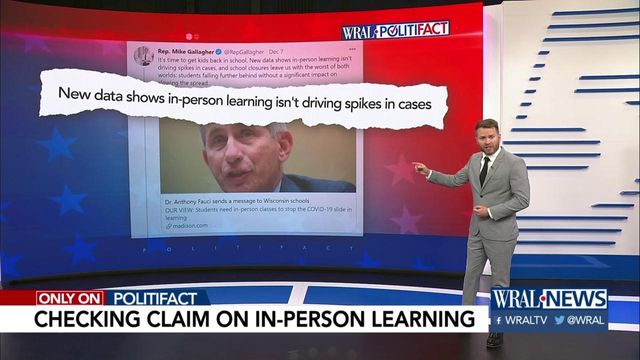

Fact check: Congressman says in-person learning 'isn't driving spikes in cases'

Research from an array of sources in October and November show in-person instruction has not been tied to increased cases in those areas. Key leaders including Fauci have acknowledged classroom instruction caused fewer issues than expected, leading him to support a shift away from virtual learning.

Posted — UpdatedThe ideological split on in-person schooling during the pandemic was pretty predictable through most of 2020.

Those who generally favored lockdowns and other strong mitigation measures opposed in-person schooling, while those who derided lockdowns, mask orders and the like typically supported it.

Like much related to COVID-19, however, positions have shifted on this issue as more data and studies have emerged.

One prominent Wisconsin Republican says that research now supports a more widescale return to the classroom.

"It's time to get kids back in school," U.S. Rep. Mike Gallagher, R-Green Bay, said in a Dec. 7, 2020, tweet. "New data shows in-person learning isn't driving spikes in cases, and school closures leave us with the worst of both worlds: students falling further behind without a significant impact on slowing the spread."

Is Gallagher right that in-person learning isn’t driving a spike in cases?

In a word: Yes.

The cost of online schooling

The push against virtual schooling — embraced by most school districts starting in March — has strengthened as a growing body of research shows the toll being out of the classroom takes on learning.

Meanwhile, the science shows school doesn’t present the risk many experts expected.

What we’ve learned from the schools that opened

As with many other pandemic response measures, the diversity of local guidelines governing schools has created a natural experiment.

Even Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, is now advocating for a measured return to in-class instruction.

"The default position should be to try as best as possible within reason to keep the children in school, or to get them back to school," he said on ABC’s "This Week" on Nov. 29, 2020. "If you look at the data, the spread among children and from children is not really very big at all, not like one would have suspected. So, let's try to get the kids back, but let's try to mitigate the things that maintain and just push … community spread" like capacity seating indoors at restaurants and bars.

(Wisconsin was notably worse in both categories, averaging 7 infections per 1,000 students and 19 per 1,000 staff members)

CDC data shows children under age 18 make up about 10% of cases in the U.S., though they comprise 22% of the total population. (Children account for just 0.1% of deaths.)

The key asterisk is that in-person instruction is safest when mitigation measures remain in place in both schools and the community.

Jordan Dunn, press secretary for Gallagher, cited this research and Fauci’s comments in defending Gallagher’s statement.

"That’s not to say there isn’t transmission in schools and schools should re-open without common sense safety measures," Dunn said in an email. "But the data that has been collected suggests, as Rep. Gallagher states, that in-person learning is not driving spikes in cases and schools are not super-spreaders."

PolitiFact ruling

Gallagher said, "New data shows in-person learning isn't driving spikes in cases."

Indeed, research from an array of sources in October and November show in-person instruction has not been tied to increased cases in those areas.

Key leaders including Fauci have acknowledged classroom instruction caused fewer issues than expected, leading him to support a shift away from virtual learning.

We rate this claim True.

Related Topics

Copyright 2024 Politifact. All rights reserved.