Holograms and altered images: North Carolina candidates decry attacks that 'fabricate reality'

North Carolina candidates are crying foul about political ads that present voters with a false, but convincing reality.

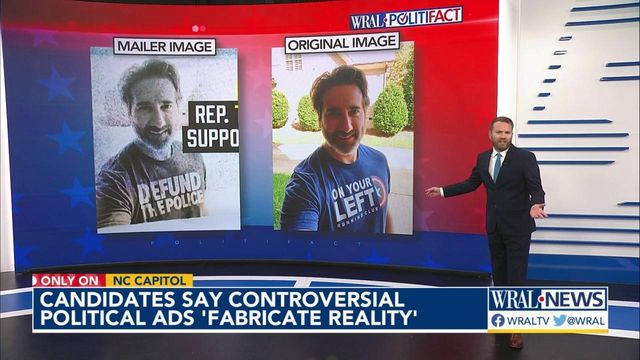

Posted — UpdatedMail ads showing legislators in “defund the police” shirts that they didn’t wear.

A digital ad depicting a legislative candidate in front of a police lineup wall, even though he wasn’t arrested.

A television ad featuring a hologram meant to mimic a congressional candidate, using a fake voice to speak his actual words.

They’re all examples of a trend in North Carolina political advertising, which one candidate referred to as “fabricating reality.”

Political advertisers have long been known for spreading falsehoods about their opponents. For decades, attackers have published misleading claims about candidates and circulated unflattering photos of them. It’s common for operatives to manipulate photos in small ways, often by exaggerating candidates’ wrinkles or darkening the bags under their eyes.

But this election season, some North Carolina candidates are crying foul about ads that present voters with a false but convincing portrayal of reality.

“I'm used to them being dishonest with cutting my face out (of photos) and doing that sort of stuff,” said state Rep. Terence Everitt, one of the Democratic targets of the “defund the police” mailer. “But this was another level of dishonesty.”

Brian Echevarria, a Republican legislative candidate whose image appeared in front of the police lineup wall, said the ad made him feel terrible. “My first thoughts were, ‘What about my children, my wife and my parents?’ and how embarrassing and hurtful this would be for them.”

The ads with fake-but-realistic-looking T-shirts, police mugshots and computer-generated images, though, are leaving candidates and media experts startled.

When an ad features a caricature, “it becomes obvious that the creator took some liberties with the truth in order to editorialize—to make a point,” Amanda Sturgill, author of the book “Detecting Deception: Tools to Fight Fake News,” said in an email.

The faked T-shirts are more nefarious, said Sturgill, an Elon University journalism professor.

“With a doctored photo like these,” she said, “it’s a lot less obvious and feels less like editorializing and more like deception.”

Ads in legislative races

The doctored images of legislative candidates have generated outrage on social media. They’ve even prompted calls for legal reforms.

The ads designed to falsely depict Democratic lawmakers in T-shirts with the words “defund the police” were commissioned by a conservative political group known as the Carolina Leadership Coalition. The group targeted state Reps. Ricky Hurtado of Alamance County and Terence Everitt of Wake County, who, respectively, face Republicans Stephen Ross and Fred Von Canon in the general election. Their races are expected to be among the closest in the state.

Michael Luethy, a spokesman for the coalition, acknowledged that the photos were altered, but he rejected the idea that the ads are unfair. He considers them a caricature that reflects what he describes as Hurtado’s and Everitt’s support for a pledge they signed on FutureNow.org, the website for a liberal advocacy group.

“With violent crime threatening neighborhoods across the state, I can see why they would try to distract the public from their records on the issue,” Luethy said. “But their dishonest smokescreen won’t fool anyone.”

Everitt and Hurtado each told WRAL that they don’t want to defund police and that their pledges don’t indicate that. Everitt said he believes some law enforcement duties can be shifted to specialists, particularly when dealing with mental health crises and drug intervention efforts. Earlier this year, the North Carolina Sheriffs’ Association announced that a majority of its members no longer want to be involved in transporting patients who are being involuntarily committed.

It’s unlikely that anyone accused of wanting to “defund the police” would suffer enough tangible harm to muster a strong defamation case, legal experts say. Someone accused of being arrested, however, might have a better case.

Echevarria, the Republican candidate at the center of the fake mugshot, said he was surprised that his opponent would wade into a fight over criminal records.

The ad claims that Echevarria was “charged with passing a bad check” and shows his face and torso in front of a height chart along a police lineup wall. The Staton-Williams campaign cited court records from Florida showing Echevarria was charged with passing a bad check in 1998.

Echeverria acknowledges the bad check and bankruptcy on his campaign website. Republicans claim the ad gives the impression Echevarria was arrested, which he wasn’t. The case against Echevarria was dismissed.

State Republicans, meanwhile, have said Staton-Williams has her own history of legal troubles. One mailer by the state GOP says she was convicted of “lying to authorities,” citing Mecklenburg County court records.

Staton-Williams said in an email that her campaign ads are intended to illustrate “an extensive pattern of financial mismanagement.” When then asked to comment on her own record, Staton-Williams didn’t respond.

Few legal avenues

It’s rare for candidates to succeed in court when challenging political attack ads. And it’s even more rare for a candidate or campaign to become the focus of a criminal probe because of allegations they placed in an ad.

“It's incredibly difficult to get into legal trouble as it relates to misleading political ads,” said Philip Napoli, a Duke University professor who researches media regulation and policy.

The ad accused Stein’s Republican opponent, Jim O’Neill, the Forsyth County District Attorney, of leaving rape kits “sitting on a shelf.” While O’Neill has argued that district attorneys don’t have direct control over rape kit testing, Stein’s campaign has claimed they have influence over rape kit testing because they’re in charge of which sexual assault cases are prosecuted. Stein’s campaign has also argued more broadly that the ad isn’t any more misleading than ads aired by O’Neill and other political candidates.

O’Neill hasn’t responded to requests for comment.

Historically, candidates seeking recourse take their complaints to civil court and sue their attacker for defamation. Winning those arguments can be difficult. Candidates must be able to prove that the false claims caused them real-world damages—for example, by jeopardizing the candidate’s ability to make money.

One of the few successful defamation cases in North Carolina took 14 years to settle. The campaign for Roy Cooper, while running for Attorney General in 2000, aired an ad claiming that his Republican opponent, Dan Boyce, charged $28,000 an hour to represent taxpayers in a lawsuit over a tax on stocks and other securities. The sides reached a settlement in 2014, with Cooper agreeing to issue an apology and pay $75,000.

“This is a very expensive and lengthy method of dealing with the complaint,” said Michael Weisel, a managing member at Capital Law Group and a longtime expert in North Carolina election law.

“This also doesn’t fix the immediate problem of stopping the advertisement from running,” he said in an email.

If a candidate wants to fight a false claim appearing in a television, radio or newspaper ad, his campaign typically issues cease-and-desist letters to the media outlet sharing it—warning the outlet that they could be held liable for damages. That’s what the Hines campaign did earlier this year when a Texas-based group showed a digital representation of the candidate mouthing the words, “I’m a lot more liberal on certain social issues.”

Mainstream media outlets hesitate to remove political ads because they can be accused of political bias and, in some cases, are discouraged by law from doing so. There’s no video or audio of Hines saying the words that were mouthed by his image in the ad. However, the partial quote was attributed to Hines in a 2017 article by the Hartford Courant newspaper while Hines was a student at Yale University.

Around the time Hines won the GOP primary, the ad faded from the airwaves. It’s unclear how a complaint about computer-generated videos of candidates might play out in court. North Carolina’s statutory and judicial framework is ill-equipped to deal with such technologically-driven conundrums, Weisel said.

“Are using holograms, superimposed clothing or signatures illegal or impermissible to graphically illustrate a campaign point, assuming the underlying premise is accurate and truthful?” he said. “There is some case law and statutes prohibiting such digital alteration, but these have been generally confined to prohibiting use of ‘celebrity’ images and recordings.”

Hurtado, one of the Democrats targeted with the fake “defund the police” shirts, thinks lawmakers should find a way to ban political ads that present voters with false images of candidates.

“There will certainly be a free speech debate about false statements and political ads,” Hurtado said. “But I think that there can be a line drawn when it comes to doctoring documents or images. You're clearly doing that to manipulate the truth.”

In the meantime, political groups can continue to enjoy what Napoli, the Duke professor, called an “incredibly hospitable” environment for lying in attack ads. The freedom of speech allowed under the First Amendment mostly leaves candidates, the news media and voters in charge of fact-checking misleading political claims.

The effectiveness of what Napoli referred to as “counter-speech” will certainly be tested.

Related Topics

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.