Courts vs. legislature: A multibillion-dollar NC education funding dispute is headed to standoff

The goal is better teachers and principals, more support for struggling students and more learning opportunities, especially for the state's low-wealth counties. But the state's top lawmakers don't intend to fund a plan laid out by a judge.

Posted — UpdatedThe goal is better teachers and principals, more support for struggling students and more learning opportunities, especially for the state’s low-wealth counties.

But the state’s top lawmakers don’t intend to fund it.

“With all due respect to the court, it is not the responsibility nor the authority of a judge to direct how funds are spent in this state,” House Speaker Tim Moore said. “That is entirely the responsibility of the state legislature.”

By law, the state is supposed to fund education. Counties can levy property taxes to raise additional funds for education. But the state constitution says all children are entitled to a “sound basic education.”

So, in 1994, five school boards from the state’s poorest counties sued, arguing that the state wasn’t doing that and that they couldn’t raise enough local tax revenue to pay for local schools themselves.

Courts have sided with them in what’s now known as the Leandro case.

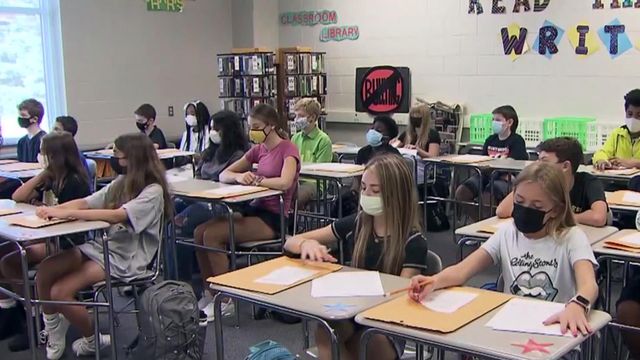

While the lawsuit dates back 27 years, concerns over resources to fund education has been compounded by disrupted learning and lower test scores that resulted from the coronavirus pandemic. The impact of three federal stimulus packages sending more than $5 billion to North Carolina has been muted by high turnover and a lack of job applicants, mostly for the lowest-paid positions.

Two branches of government collide

How the state should address the Leandro court rulings is disputed between political parties.

“I think it shows you a lot about kind of where we are in terms of politics and government in North Carolina that so many people jump right to, ‘What happens if there's a complete standoff between the courts and the legislature on this issue?’” said Matt Ellinwood, director of the North Carolina Justice Center’s Education Law Project, which favors the so-called Leandro plan.

Part of the argument made by Republicans is that lawmakers weren’t a part of the process developing the plan. The General Assembly isn’t a party in the case and, though implicated in the court rulings, haven’t intervened in the case.

Senate President Pro Tem Phil Berger notes that lawmakers had meetings with the former judge presiding over the case, Howard Manning, but that the new judge hasn’t accepted an invitation to talk with them.

Superior Court Judge W. David Lee, who now presides over the case, says he’ll consider suggestions on Oct. 18 to compel lawmakers to fund the Leandro plan. The plaintiffs in the case have already argued for Lee to do so.

Even if he does take action, legal experts say the path forward would still be unclear.

“For our legislature to say, 'We don't have to follow a court command,' that's problematic. You know, because the courts do have the power to say how the constitution ought to be interpreted and how a violation ought to be remedied,” said Ted Shaw, Julius L. Chambers Distinguished Professor of Law and the director of the Center for Civil Rights at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

School funding lawsuits in other states have lasted years, even decades. Often, lawmakers have tried to comply with court rulings.

“When the legislature refuses to do it, frankly, there isn't a very clear answer about how this ultimately will get resolved,” Shaw said. “It's not an easy scenario. It's not ideal. It's a failure of governance.”

Different spending priorities

Both budgets include additional education spending outside of the Leandro plan, such as an increase in tuition vouchers for private schools.

The state has $5.7 billion in unspent revenue from last year. But other plans and proposed tax cuts totaling $2.5 billion in the next two years would reduce the state’s budget flexibility.

North Carolina spends far less per student than all but a handful of states. Federal data from a 2018 survey showed North Carolina is the ninth-lowest in spending per student, at $9,500. Spending in South Carolina tops $11,000 per student, and in Virginia, it’s well over $12,000.

Annual education spending increases in North Carolina have been lower since the 2008 recession, though they've recently picked up pace. Experts argue educators’ and school employees’ pay hasn’t always increased with inflation since that time.

But lawmakers note North Carolina, as a state, has better than average outcomes in many national tests. Though that’s not true for every school district.

“So, if more money equals better outcomes, you wouldn't see that, and you see it time and time again,” said Berger, R-Rockingham.

Yet, the Leandro case is about money.

The state Supreme Court agreed the state wasn't doing its part to fund education, first back in 1997 and again in 2004.

The “defendants have failed in their constitutional duty to provide such students with the opportunity to obtain a sound basic education,” the court wrote in 2004 “In addition, this court affirms the trial court’s ruling that the state must act to correct those deficiencies that were deemed by the trial court as contributing to the state’s failure of providing a Leandro comporting educational opportunity.”

Providing a ‘sound basic education’

- Developing, recruiting and retaining teachers

- Developing, recruiting and retaining principals

- “Adequate, equitable, and predictable” funding and resources to schools

- Student performance and accountability that meets a “sound basic education”

- Creating an assistance and turnaround system for low-performing schools

- Improving and expanding early childhood education and pre-kindergarten

- Aligning high school and postsecondary and career expectations and opportunities

The plan is extensive. It calls for more support resources and staff, removing the cap on funding to educate children with disabilities, opening more pre-kindergarten classes and giving districts money to create locally determined plans to address struggles students have outside the classroom. Some of the raises are designed to draw people to jobs in North Carolina that pay less than they do in other states, such as school psychologists.

North Carolina Republicans emphasized their own priorities to WRAL News: an effort well underway toward improving the state’s reading instruction, as well as increasing access to vouchers for limited private school seats.

They’ve invested in many other things in the Leandro plan, such as raises for educators and expanding the Teaching Fellows programs at the state’s historically Black colleges and universities. They’ve just not invested to the extent the plan calls for.

Both Moore, R-Cleveland, and Berger touted those efforts, along with their goal to increase Opportunity Scholarships, the private school voucher program for families who can’t afford to pay full tuition themselves.

If schools are indeed failing children, both said, families should have the option to send their children elsewhere.

But Moore acknowledged not enough seats exist at other schools to theoretically transfer everyone out of a failing school.

“You're never going to have enough alternate choices there, if you will, so that every student would be taken care of," he said. "It's not something that would work, but you could take care of a lot of those students."

Berger and Moore wouldn’t say whether they’d ever fund the entire Leandro plan. When WRAL asked them which line items they specifically disagree with, they didn’t identify any.

So, do lawmakers think North Carolina is already providing a “sound basic education?”

“I don’t think anybody would think we’re where we need to be in terms of educational outcomes,” Berger said. “So, I don’t think there’s a lot of disagreement on that.”

Related Topics

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.