Meant to offer 'HOPE,' state rental assistance program has been slow to pay

Tenants, landlords and utility companies are kept waiting as grant money promised takes weeks, even months, to deliver.

Posted — UpdatedPayment hold-ups led to utility cutoffs, threatened evictions, fearful tenants and anxious landlords. Applicants who call or email for help often say they haven’t heard from a caseworker for more than a month.

They complain of gas, electricity and water cutoffs and of situations getting more desperate by the day. With $550 million in federal funding queued up to expand this program, some lawmakers worry whether the state agency in charge can handle it.

“When they said they’re going to help, I was expecting help within weeks,” said Ashley Davis, who lives in Vass and applied for aid in October. “It’s been months.”

Davis, who is working again after being laid off from a restaurant job, said the program paid her power bill almost immediately. But it didn’t pay her rent or her water, which got shut off.

Alanna Dean, a single mother in Raleigh laid off from a sales job, said she was surprised when her gas got shut off. She owes $350 to Dominion Power and another $3,500 in rent at the apartment where she and her two toddlers live.

Dominion turned Dean's gas back on within hours of WRAL News calling. A company spokeswoman said they didn’t know Dean was part of the state's rental and utility assistance program, and Dean said her landlord has similar issues.

“I keep telling her that I was approved for this program,” Dean said. “She’s like, 'Well, they have not reached out to me,’ and she’s giving me a notice to vacate.”

The program is called HOPE – Housing Opportunities and Prevention of Evictions – and it’s a state initiative to use coronavirus money from the federal government to keep renters in their homes.

State officials running the program say they understand people’s frustrations. They built HOPE from scratch in the late summer and, when it went live in mid-October, they were inundated by more than 42,000 applications.

Some of the delay is by design. The award letter protects tenants from eviction while program officials collect the necessary paperwork, like leases and utility bills, and cut a check.

“We purposefully front-loaded that,” said Laura Hogshead, chief operating officer for the North Carolina Office of Recovery and Resiliency, which runs the program. “We wanted people to have the assurance as soon as they could.”

“The problem with the HOPE program is that the monies have been coming out very slowly,” Robertson said.

Asked last week about the discrepancy, Cooper spokesman Ford Porter agreed the distinction “is important,” but he stressed that once an award has been decided, “landlords and utility providers are provided certainty of payment and cannot evict tenants or shut off their utilities.”

Hogshead acknowledged complaints about the pace, and she said changes made in January to automate some of the process and open a 24/7 online portal where people can upload leases, utility bills and other documents is speeding things up. More changes have been made since or are underway, a program spokeswoman said Monday.

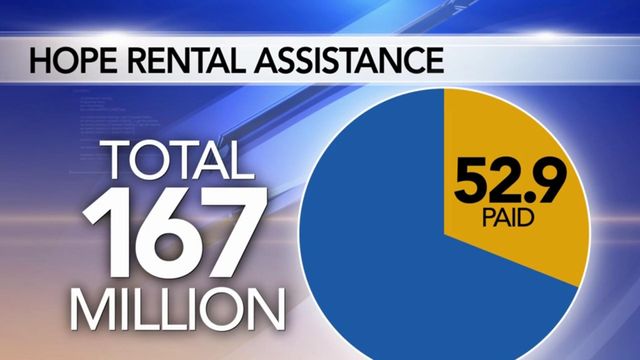

Awards took a big jump in January, but then the numbers steadied. As of Feb. 3, the Office of Resiliency and Recovery put awards at about $133 million and payouts at $42 million. By Monday, those figures had gone up to $137.5 million and $52.9 million.

Hogshead said state has about 150 people working on the program, most of them temporary employees, plus workers from roughly 20 community partners. The partners are nonprofits, for the most part, that write checks, then seek reimbursement from the state.

“We are pushing the funds out as fast as we can,” Hogshead said.

'I am in dire straits'

That hasn’t been fast enough for some.

Phyllis Wilson used to work at an Amazon distribution center but said she has health issues that make the coronavirus particularly dangerous for her. When she applied for assistance, Wilson wasn’t far enough behind on rent to qualify, but she said the state promised to pay $211 toward her electric bill.

That was in December. Wilson said she found out this month that the bill hasn’t been paid after her power company threatened to disconnect her. As of Friday, she expected a disconnect any day but hoped to borrow money to avoid it.

“I thought this whole time that the HOPE program had taken care of the bill,” she said.

Those sorts of concerns pepper a database the state keeps on HOPE program inquiries. WRAL requested just a week’s worth of those calls and emails, and the Office of Recovery provided a list of 249, all names and contact information redacted.

Many said their water or electricity had been shut off or was about to be. Many feared eviction. Some said they had young children or someone with a disability in their homes.

Nearly a dozen said they hadn’t heard from a program caseworker in at least 30 days. Applicant after applicant said they weren’t able to upload required documents through the state’s online portal. Some said their landlords – more than half the landlords involved in the program are small operations, owning just one or a few properties – didn’t understand the program.

A lot of the cases sounded like Nicole’s.

Nicole told WRAL that she was furloughed in March, that she has a respiratory condition and that her young daughter is in virtual school. She got some unemployment benefits and stimulus checks from the federal government, but she’s used credit cards to pay crucial bills, including her last overdue water bill, which she split over three cards.

Nicole asked not to be identified by last name. She said her HOPE funding was approved in mid-December, but nothing has been paid. She said her water was disconnected once, then turned back on after a HOPE program supervisor called the company.

“My landlord has continued to send me messages demanding payment that I don’t have, and I don’t know what to do,” Nicole said. “I have contacted the (HOPE) caseworker many times, but they have no answer and no resolution as to when my agreement might be funded.”

“I am in dire straits,” Nicole said in an email. “Trying to keep our heads above water but I don’t know what to do next.”

State data not shared with local assistance programs

The HOPE program pays up to six months rent for people who meet various qualifications, including an income cap at 80 percent of their area’s median income.

It’s one of a handful of rental assistance programs that popped up during the pandemic in North Carolina, but it’s the largest by far. Wake County has a sister program, with about $15 million in funding.

Wake’s housing agency brought in Telamon, a nonprofit based in Raleigh but with operations in 11 states, to run its program. To avoid double-dips, Telamon said it sent its applicant data to the state’s HOPE program about a month ago, expecting the state to do the same.

“Haven’t gotten anything back,” Telamon President and Chief Executive Suzanne Orozco said. “At this point, I’ve kind of given up on that.”

Orozco said some of the people who applied through Wake County’s program told caseworkers they’d expected to get help from HOPE, but reached out when a check didn’t come.

“I don’t want to throw them under the bus,” Orozco said, “because we’re still crawling out from under a stack of applications ourselves.”

Asked about the failure to share data, a spokeswoman for the Office of Recovery and Resiliency said last week that the state “initiated the data sharing agreements with entitlement communities and is executing on those agreements now that rent awards and utility awards are being finalized.”

Both the state and local assistance programs are about to get massive cash infusions from the federal government. The current programs were built from broad coronavirus funding that Congress approved last spring. But in December, Congress passed another stimulus bill, and this one had money earmarked specifically for rental assistance.

North Carolina’s share is about $700 million, with nearly $550 million flowing through the state and the rest broken up among the state’s largest local governments, which will run their own programs. The state is still awaiting final guidance from the U.S. Treasury for just how the program will work, but because of the way Congress wrote the stimulus bill, it will have different rules than the current HOPE program.

Hogshead said her agency is ready to take the reins of the larger effort.

“We have improved our process, and we’ve learned along the way,” she said.

Not everyone is convinced, and lobbyists for landlords and other industry groups have the ear of at least some members of the General Assembly, who could redirect the money to other groups to run a similar program.

“This is a mess from what people in the Legislative Building have been telling me,” said Rep. John Szoka, R-Cumberland. “The question I’m trying to answer for myself … can we fix it good enough to get the money to the people who really need it?”

Telamon's president, Orozco, said the state approached them about managing the new, larger program.

"When I heard the number, I was just like, 'We don’t have that capacity,'" she said. "There was just no way."

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.