Closing tax 'loopholes' could be painful for all

Advocates of tax reform says the state needs to get rid of tax breaks for special interests. But many "loopholes" in the state's tax code are breaks used by average citizens, nonprofits and small businesses.

Posted — Updated"We should also look to close tax loopholes," Gov.-elect Pat McCrory said during the primary when The Associated Press asked him about plans for sparking the state's economy. "Republicans and Democrats need to put politics and special interests aside and work together for the creation of a more fair and modern tax code which rewards productivity, innovation and creates jobs."

That pitch would have been at home in the stump speeches of Democrats and Republicans alike.

So, who are all these freeloading loophole users? Are we talking about big corporations and wealthy individuals with slick accountants?

To some extent, yes. Few of will us will take advantage of tax breaks on flight simulators or worry about levies on commercial logging equipment.

But if you're looking for those who take advantage of some of the costliest exemptions in the state tax code and could end up paying more under any reform effort, take a long, hard look in the mirror, North Carolina.

All those breaks ad up to $9 billion. That's equal to roughly half of what North Carolina spends in state-raised revenue every year. It's a tempting rhetorical target, considering collecting even half that money would allow the state to lower tax rates, sock away savings for a rainy day and have a cushion for when tax reform takes hold in earnest.

But the five costliest exemptions on that list are not handouts to industry. Rather, they are deductions taken by nearly anyone who files a tax form and some who don't:

- Standard and itemized income tax deductions (total value: $2.3 billion)

- Personal exemption on income tax ($2.2 billion)

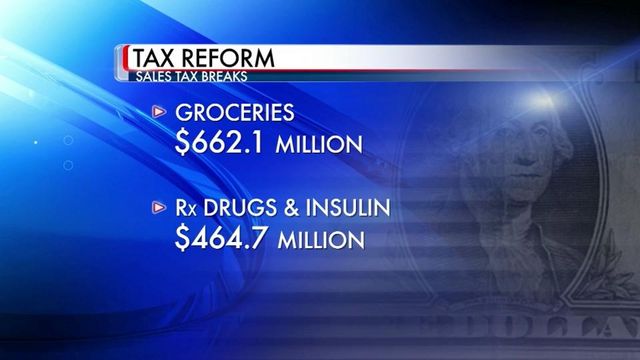

- Sales tax on groceries for home consumption ($662.1 million)

- Sales tax on prescription drugs and insulin ($464.7 million)

- Income tax exemption on certain government retirement income ($428.8 million)

Added up, that's $5 billion in tax breaks that pretty much every man, woman and child in the state take advantage of on a fairly regular basis.

"I'd hate to run for office on the platform that I'm going to do away with charitable giving as a deduction, and too bad if you got sick this year, we're taking away that deduction," said Douglas Shackelford, Meade H. Willis Distinguished Professor of Taxation at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Just as Congress is wrestling to reform an unwieldy federal tax code, state lawmakers are trying to navigate the political and economic pitfalls that come along with making North Carolina's tax code simpler.

Part of the problem with any tax reform effort – and there have been at least seven in North Carolina over the past 25 years – is the reality of doing away with "tax expenditures" requires the slaughter of sacred cows. Many of those deductions, credits and exemptions developed as a way to make the tax code more equitable and take into account different groups of people's ability to pay.

"If you've got five kids, maybe you're in a different position than someone who doesn't have any kids. If you're married, maybe you're in a different position than if you're taking care of an elderly parent or if you're blind," Shackelford said. "It's all an attempt, rough as it may be, to try to get some fairness."

In other cases, breaks are relatively new, crafted by the people now in charge of tax reform. For example, a business income tax deduction created in 2011 will allow small businesses to deduct $50,000 in income from their liability. The Department of Revenue estimated this break will costs the state $131.6 million a year, but other estimates are three to four times higher. Its exact value probably won't be known until next April or May, when final tax returns for 2012 roll in.

Another problem for those seeking to eliminate exemptions, particularly sales-tax exemptions, is "cascading."

This effect occurs when the raw materials used in production are taxed. For example, packaging bought by manufacturers is exempt from sales tax. The logic is that the end-consumer will ultimately pay sales tax on the cost of that item, and if a manufacturer pays sales tax on a cardboard box, that extra cost merely gets passed on to a consumer. Eliminating exemptions for such business-to-business transactions could increase the price of consumer goods.

"If I could figure out to get rid of sales tax for all business-to-business transactions, I'd win a Nobel Prize," said Sen. Bob Rucho, R-Mecklenburg, who is one of the lawmakers leading this year's tax reform push.

"This could turn into the lobbyist full-employment act," Rucho joked.

Clearly, just eliminating the smaller, quirkier breaks won't get the state very far. Charging excise tax on the sacramental wine bought be churches, for example, would recoup less than $100,000 per year. Revoking a $250 annual credit for firefighters would claw back only $300,000.

But the more money a particular exemption brings in, the harder an industry can be expected to fight for it. Consider the list of items are tax exempt if they are sold to farmers:

- horses and mules

- farm machinery, related parts and lubricants

- fertilizer and seeds

- fuel used for farm purposes

- electricity sold to run farm equipment

- containers and storage facilities

- feed, litter and medication

- pesticides

- tobacco farming items

Taken together, those breaks add up to nearly $250 million in tax-exempt sales every year.

"The farming community would like to be supportive of whatever is proposed," said Peter Daniel, the assistant to the president of the North Carolina Farm Bureau. "But the issue becomes, the farm economy is fairly fragile."

Farmers are different from manufacturers, he said, because they can't just raise the price they charge for a product. Commodity prices are set on trading markets, so an extra tax comes out of the farmer's bottom line.

The Farm Bureau is one of the most influential lobbies at the General Assembly.

Similarly, virtually any tax loophole slated to be closed is likely to have its own defender. Automobile dealers, for example, have opposed efforts to fully apply sales taxes to car sales. The film industry professionals in Wilmington and Winston-Salem say credits for productions are needed to lure big Hollywood pictures to the state.

But making sure that everyone is treated as fairly as possible is key to the tax reform effort, Rucho said. Creating loopholes for one industry will cause others to ask for their own exemption.

"Everybody should be treated the same," he said.

Related Topics

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.