Wake diverts mentally ill from ER to treatment

A Wake County program designed to get faster treatment for people with mental illness and cut medical costs is garnering national attention.

Posted — UpdatedOf the nearly 90,000 Wake County EMS runs this year, about 5 percent were for people with mental health or substance abuse problems. In the past, paramedics took them straight to a hospital emergency room, but the county has changed that practice.

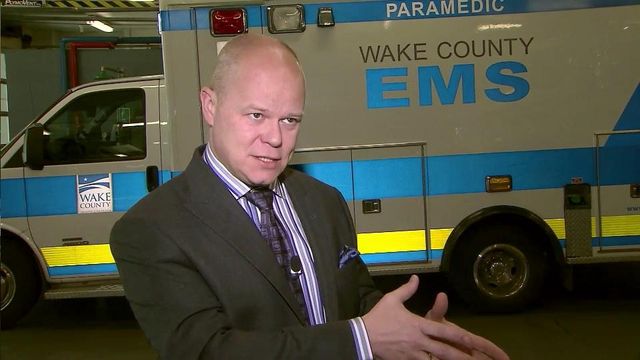

"That is a broken model," said Dr. Brent Myers, Wake County EMS director. "Patients are not calling us because they need to go to the (emergency room). They're calling us because they need help, and we're trying to modify to meet the patients' needs."

Paramedics went through training to better identify non-medical issues, and in the past year, EMS diverted 350 people to the WakeBrook Campus, a crisis care and recovery center in Raleigh operated by UNC Health Care, and other places that specialize in mental health care.

"It's been nice to give them an opportunity and give them another resource other than just simply taking them to the emergency room and continuing that cycle," EMS supervisor Michael Lyons said.

The state Department of Health and Human Services last month called the program a model for a statewide crisis intervention program to keep people with mental health and substance abuse problems out of hospitals. This week, the Wake County program was profiled on the front page of The New York Times.

"It's catching on across the country because it's the right thing to do," Myers said.

Studies show that mental health patients typically take up 14 straight hours of emergency room bed time, so diverting them saves money and time and frees up resources.

Hospitalization costs related to the mentally ill are expected to jump from $20.3 billion in 2003 to $38.5 billion next year, according to federal estimates.

"The nice thing about that is, oh, by the way, it's better for the health care community, it's better for health care economics," Myers said. "But that's not where you start. You start with what's right for the patient."

Mental health advocate Ann Akland said the Wake County program only works if North Carolina has enough beds and care outside of hospitals for the mentally ill.

"It's a great thing to divert them from the ER as long as there is capacity," said Akland, who heads the local chapter of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill. "What's going to happen is they're going to show up someplace else. If there aren't hospital beds, they're going to be on the streets. They're going to be picked up."

WakeBrook Campus medical director Dr. Brian Sheitman blamed the dearth of community treatment options, in part, for estimates that show the number of people with mental illness entering hospital emergency rooms in North Carolina is double the national average.

"When the state hospital closed that level of service (on the Dorothea Dix campus), it's been hard to replicate that in the community," Sheitman said.

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.