Changing Medicaid to managed care could take years

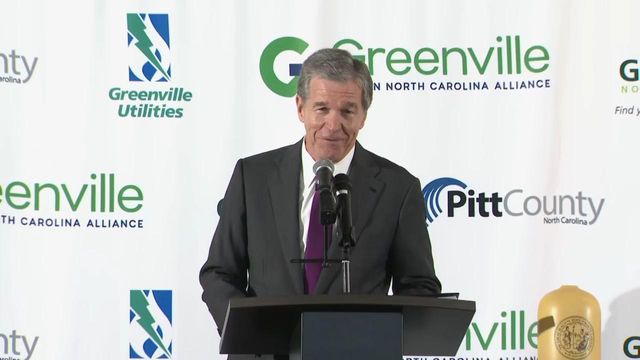

Gov. Pat McCrory's signature on House Bill 372 wasn't the end of North Carolina's effort to change how the state's $14 billion Medicaid system works.

While the political wrangling may be over for the moment, the real work of changing how poor and disabled North Carolinians get health care is just beginning. Administration officials are only in the nascent stages of building the division that will be responsible for crafting and running the new program.

Nobody knows exactly what Medicaid will look like when it emerges from its bureaucratic chrysalis.

Lawmakers gave McCrory's administration nine months to birth a new agency to oversee Medicaid and submit a proposal for a new Medicaid system to the federal government. That new system has no exact model to draw on from any other state, and state officials will have to negotiate a thicket political and practical questions. Those range from big-picture issues such as whether North Carolina should extend Medicaid benefits to currently unserved groups of people to technical questions like how to keep newly created "provider-led entities" solvent.

"I think most everyone's guess is this is a one- to two-year process to get the waiver approved," said Lanier Cansler, a former Department of Health and Human Services secretary who now runs a health care consulting firm.

After that, actually making the changes will likely take another 18 months, according to rough timelines included in the authorizing legislation."I would say the passage of the law might mean things are 5 percent done, 95 percent left to do," said Don Taylor, a health policy expert at Duke University's Sanford School of Public Policy.

At lightning speed, the changes would happen in about three years. Five years would not surprise anyone, Taylor and Cansler said.

How the new system evolves from a 12-page bill to hundreds of pages of rules and guidelines will have massive implications for the one in five North Carolina residents who are Medicaid patients, their doctors, their communities and taxpayers. While proponents see the potential for a new model that ensures high-quality care for the state's most vulnerable residents, pessimists like Taylor see Medicaid transformation being strangled by the complexity of the task at hand.

"The most likely outcome will be nothing will happen at all," Taylor said.

Others say the state has little choice but to push forward toward a new way of paying for health care, even if it's not exactly what's envisioned by the bill that passed this summer.

"This legislature is going to stay on it, to push to get it to happen," Cansler said.

Laying the groundwork for change

Medicaid is a public health insurance system jointly funded and overseen by the state and federal governments. North Carolina's redrawing of the system will also encompass North Carolina Health Choice, a program that provides insurance for children in families who earn too much money to qualify for Medicaid but too little to afford private or employer-sponsored health insurance.

This system has long been a political football in the state. Although the federal government pays the lion's share of the system's costs, lawmakers begrudge the $3.7 billion of state funds the Division of Medical Assistance sops up, arguing it is a growing portion of state spending that pulls money away from education and public safety needs. Five years ago, the division that runs Medicaid took up $2.7 billion, although it's important to point out that the health insurance program is an entitlement whose use increases during economic downturns.

Although audits of the program have raised concerns about money management, other reviews of the system have lauded current features, including CCNC, a nonprofit network that helps doctors manage Medicaid patients.

Over the next five years, if the guidelines laid out by House Bill 372 are followed, virtually all Medicaid services will be delivered through a managed care model. The two exceptions will be dentistry services and services for "dual eligibles," those older patients who qualify both for Medicaid and Medicare, the federally run health insurance program for the elderly.

Lawmakers have long agreed that Medicaid should move to a managed care system, but members of the House and Senate have battled over the past three years what that system should look like. Roughly speaking, senators have argued for a system run by large, national managed care companies while members of the state House have sought to foster home grown "provider-led entities," in which doctors and hospitals would assume the lead in both patient care and assuming the risk associated with the cost of that care.

The final compromise creates a two-layer system that stitches together both ideas. Authors of the plan say patients will choose which network they want to provide their care, and that choice will keep both kinds of insurers on their toes.

"This, to me, is not so much about reducing the costs," said Rep. Donny Lambeth, R-Forsyth, a retired hospital executive who helped draft the Medicaid transformation bill. "It's about improving quality and access."

The new system provides three statewide slots for companies that would have to care for patients across the state. These could be traditional managed care firms or one of the new provider-led entities. In either case, the companies would need to demonstrate they had contracts with enough doctors, hospitals and other health care providers to serve patients from the coast to the mountains.

A second tier of the system carves North Carolina into six regions. Only provider-led entities with ties to physician groups or other locally based health care companies would be eligible to compete for business in the regions.

Not only would companies have the incentive to provide quality care in order to attract patients, having two layers should ensure that, even if one or two companies walk away from state contracts, patients always have at least one option.

At least, that's the ideal.

"I have no preconceived notion that it's going to be 100 percent successful," Lambeth said.

North Carolina will be building a new Medicaid system in a health care landscape that is dramatically shifting, with smaller hospitals closing, doctors groups aligning with larger institutional players and all of them adjusting to the new strictures of the Affordable Care Act.

"We don't know that we're going to have competition. There are lots of unknowns that we don't know right now even though we've taken our best estimate of what the market will look like," Lambeth said.

On Oregon's trail

Although North Carolina isn't following any other state's roadmap on Medicaid, one system is mentioned specifically in North Carolina's bill: Oregon.

In particular, the new division has been instructed to use the same kind of quality metrics that Oregon has used to track the performance insurers roughly analogous the the provider-led entities North Carolina's bill hopes to create. An annual report issued by the Oregon Health Authority details how each of the state's 16 regional coordinated care organizations perform on dozens of measures.

For example, 14 of the state's 16 CCOs met benchmarks for following up with children prescribed medication for ADHD. There was a similar rate of success on a measure of how well the insurers did in reducing hospitalizations due to congestive heart failure.

"A lot of what's happening in Oregon is really promising, but it's still too early to really tell," said Aaron Mendelson, a research assistant with Oregon Health and Science University's Center for Health System Effectiveness.

Oregon's program was designed to curb the health care cost increases. Without some sort of change, the federal government predicted costs would rise about 5.4 percent per patient per year. The new system was designed to hold that increase to less than 3.4 percent.

"On paper, everything looks good," Mendelson said.

The question is why? The new structure could be doing what it was designed to do, or it could be reaping the benefits of changes in the economy and the mix of Medicaid patients.

"I don't know of another state that has the competition between the two kinds of entities. That's unique," said Mark Hall, a health care policy expert at Wake Forest University's law school.

Lambeth, said that the competition is meant to prod insurers to make sure patients can get appointments with high-quality providers or risk seeing them jump to other plans. In Oregon, there are areas where different insurers compete for patients. It's unclear whether that competition has helped rein in cost or improve quality.

"That's certainly a question that people are interested in," Mendelson said. "We haven't been able to see if competition has driven increases in quality."

Competition should also help make sure that the state won't be left in a lurch if an insurer decides the state is unprofitable and pulls out or demands a rate increase, Lambeth said.

Iowa, for example, saw the insurer CoOportunity pull out of its Medicaid program last fall when heavier use of services made its contract unprofitable. Florida insurers demanded a rate increase this year from Florida's Medicaid program when unexpectedly high drug costs cut into profits.

But along with safeguards, competition brings risks. Skeptics point out that managed care companies could artificially cut costs to driver provider-led entities out of the system, trading short-run losses for long-term market dominance.

"I suppose we could get into a situation where the established commercial insurers are willing to take much lower prices than the regional entities could undertake," Hall said. "If that were the case, the state would have to decide whether it's going to raise the price point to a level that would allow both to flourish or just go with the cheapest bidder."

With the new Medicaid division only beginning to get organized and officials with North Carolina's Department of Insurance only beginning to take a look at solvency rules, answers to those questions are a long way off. A DOI spokeswoman said her agency will need extra staff to help establish standards for the new provider-led entities.

Meanwhile, the new Division of Health Benefits just got its first employee last week. DHHS officials issued a written statement about the startup but declined to be interviewed.

"The first critical phase, which we have begun, is to listen and engage with external stakeholders. Our leaders have been meeting with health care providers and their associations," DHHS spokeswoman Alexandra Lefebvre said via email. "We will seek the experience of outside groups and identify ways to tap the expertise needed for specific work products, such as the waiver."

Cansler, the former DHHS secretary, said one problem the new division may face is finding people who have experience pitching waivers to the federal government. That may force the department to lean on consultants who have helped draft similar documents.

Another problem combines both the political and the practical, he said.

Will expansion be part of transformation?

Medicaid is not the only health insurance program aimed at low-income people. The Affordable Care Act, what some people call "Obamacare," was designed to help people buy insurance from private companies. As it was originally designed, the ACA would have required states to expand the number of people eligible for Medicaid.

But due to a Supreme Court ruling, states merely had the option of expanding. North Carolina is one of 19 states that has not expanded and is not currently discussing expansion. That has left about 500,000 low-income North Carolinians ineligible for Medicaid and unable to draw down tax subsidies on the ACA exchanges.

While the federal government can't require the state to expand the reach of Medicaid as a condition of granting the waiver, it's likely the federal government would look more favorably upon North Carolina's request if the state did so, experts say.

Taylor said there are states that have made changes without expansion but not the kind of wholesale remake that North Carolina is undertaking.

"There's certainly nobody trying to do such a big change in the era of expansion without doing expansion," he said.

Taylor and Cansler agreed that including expansion as part of North Carolina's transformation effort would go a long way toward smoothing political waters as well as solving some practical questions.

Bringing more people into Medicaid would mean fewer charity care cases for doctors and hospitals. That means a steadier stream of revenue for health care providers, particularly in rural areas, they argue. The bulk of those 500,000 patients who would be eligible under Medicaid expansion are generally younger and healthier than the typical adult Medicaid recipient, meaning that they would make the financial prospect of operating as a Medicaid managed care company or provider-led entity in the state more financially attractive.

"Quite honestly, the managed care companies who are looking at taking part, they'll push hard to look at Medicaid expansion," Cansler said.

That notion will likely meet with some resistance among lawmakers, who have barred the administration from taking steps to expand Medicaid eligibility and said that they need to get a handle on the system's current spending before bringing in any new patients.

But Lambeth said he would be surprised if the new Division of Health Benefits didn't propose expansion when they meet with lawmakers early next year.

"We're actually already talking about that," he said.

Doctors, hospitals, and other providers, he said, have been financially hurt because the state didn't expand Medicaid, and expansion could help smooth the transition to a new system. But selling that idea is far from a slam dunk, he said.

"The thing I've heard from most legislators is the unknown in terms of what that responsibility will cost down the road," he said.

Currently, the federal government will pick up at least 90 percent of the cost of new Medicaid beneficiaries in the system because of eligibility expansion. State lawmakers, he said, worry that the federal government could cut that match.

"That's a straw man argument," said Jesse Cross-Call, a health policy analyst with the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan think tank often described as "liberal leaning" in media reports.

In the history of the Medicaid program, Cross-Call said, the federal government has changed the state match only three times, all due to extraordinary events.

Lambeth said that lawmakers would at least have to openly discuss expansion, even if it doesn't come about.

"I don't think you can talk about reform without talking about the case for expansion," he said.