In Memphis, NC, across America, Martin Luther King's words, works reverberate across the decades

On the 50th anniversary of his final public speech, the words of Martin Luther King Jr. resonate across time for those making a pilgrimage to Memphis, Tennessee. Among those present when King declared, "I've been to the mountaintop," was a Raleigh woman, then pregnant with a son.

Fifty years on, Jannie Foster, an evangelist from Church of God in Christ, returned to Memphis to honor King's legacy. The day after she heard him speak at the Mason Temple on April 3, 1968, King was assassinated.

King is ever present in Memphis, and never more so than this week. At Mason Temple, there is a floral arrangement.

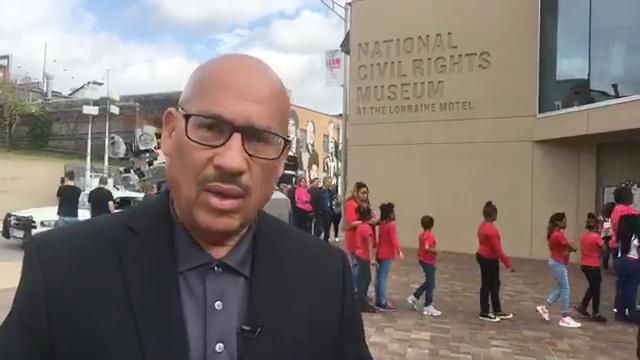

At the motel where he was slain, a world-class museum has been erected in honor of King and the civil rights struggle. And across town, at the University of Memphis, an original copy of King’s 1965 “We Shall Overcome” speech is on loan from a local philanthropist.

In concrete ways, and in far more subtle ones, Memphis is inexorably tied to King, and more than any other city, it is perceived as a place to measure the progress of King’s legacy and dreams.

But in the half-century since King was assassinated in Memphis during his peaceful crusade against pauperism and racism, the city has been immersed in poverty, segregation and violence. Its triumphs are never far from its trials.

In the beginning, Memphis seemed a worthy steward of the King legacy, swiftly electing the first African-American to represent Tennessee in Congress. In 1991, the city elected its first black mayor. (White men now fill both of those seats, despite a city population that is roughly two-thirds black residents and less than one-third white residents.)

But black financial success has never come close to matching that of politics, and King’s fight against poverty is a battle that Memphis has so far lost.

There are mighty companies — FedEx, International Paper, AutoZone — and a National Basketball Association franchise. North American mallards swim in the gilded glory of Union Avenue’s Peabody hotel. The tourism industry, drawing more than 11.5 million people every year, is built around black history and blues music, along with Memphis traditions of pork and Elvis Presley.

Still, the city that, in the shadow of the Civil War, produced the South’s first African-American millionaire — the entrepreneur, businessman and landowner Robert Reed Church Sr. — is now the anchor of the poorest metropolitan area in the United States. Manufacturing jobs have faded away, and in 2016 the city’s poverty rate was nearly 27 percent, with close to half of Memphis’ children living in poverty. The median household income was nearly $19,000 lower than the nation’s.

Crime is tragically and stubbornly high. The city logged 228 homicides in 2016, a Memphis record and many more than the larger cities of Boston, Dallas, Denver, San Francisco and Seattle. The toll was 28 lives better in 2017, but still among the highest in the country.

And so the city, a year shy of its bicentennial, feels like a place with little luster left to lose. In January, the mayor tagged population loss as the city’s greatest challenge. The gulf between rich and poor is gaping. The streets can feel desolate and forgotten, a certain sadness stretching block after block.

But the mayor also called Memphis “a city whose originality and soul has changed the world.” That, too, can surface block after block.