Disney Ends Its Fight With DeSantis Over Resort Development

In a stunning turn, The Walt Disney Co. dropped its fight against Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida for control over $17 billion in planned development at the Disney World theme park complex near Orlando, Florida.

Disney’s capitulation followed a legal setback. In January, a federal judge threw out a Disney lawsuit claiming that DeSantis and his allies had violated the First Amendment by taking over a special tax district that encompasses the company’s 25,000-acre Florida resort, which employs roughly 75,000 people.

As part of a settlement announced Wednesday, Disney agreed to pause an appeal of that ruling — but not drop it entirely — while negotiating a new comprehensive growth plan with tax district officials. Disney also agreed to stop fighting the tax district in state court, with both sides “choosing to move forward in a spirit of cooperation,” according to the six-page settlement.

“We are pleased to put an end to all litigation pending in state court in Florida,” Jeff Vahle, president of Walt Disney World, said in a statement. He added that the agreement “opens a new chapter of constructive engagement” and would allow the company to continue to invest in the resort. As part of the settlement, the district agreed not to “prohibit or impede” long-term environmental permits granted to Disney.

DeSantis celebrated the settlement, saying the state has been “vindicated” on all of its actions.

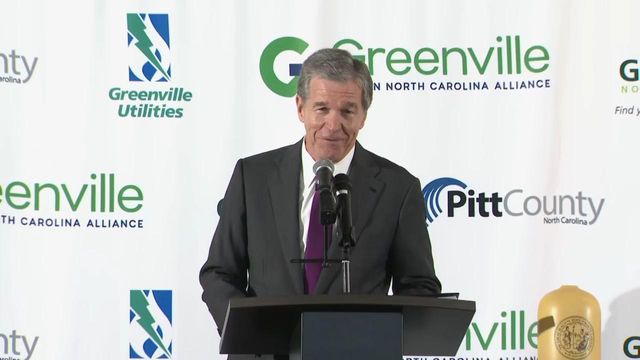

“A year ago people were trying to act like all these legal maneuvers were all going to succeed and the reality is here we are a year later, not one of them has succeeded,” DeSantis told reporters in Orlando. “Every action that we’ve taken has been upheld in full and the state is better off for it.”

The settlement followed a conspicuous leadership shake-up at the district. Two people whom Disney viewed as particularly antagonistic — the founding chair, Martin Garcia, and Glen Gilzean, a senior administrator — resigned this month. The typically outspoken Garcia, whose term would have stretched into 2027, gave no explanation. Gilzean, who had been caught in an ethics scandal in a prior government job, was appointed supervisor of elections for Orange County, which includes Orlando.

DeSantis replaced Garcia with Craig Mateer, a hospitality executive and a donor to the governor’s recent presidential campaign. Stephanie Kopelousos, a former legislative affairs director for the governor who also worked on his presidential campaign, was hired Wednesday as the new administrator. Kopelousos worked closely with Disney lobbyists during her stint in Tallahassee, Florida; three years ago, she helped exempt Disney from a restrictive social media law.

“The question now is whether Disney and the board can reach agreements that are effective and workable on many issues going forward, and the devil will be in the details that are not yet clear,” said Carl W. Tobias, a professor at the University of Richmond School of Law who has been following the case.

Disney and DeSantis, who ended his campaign for president in January, have been at odds for two years over Disney World, which attracts an estimated 50 million visitors annually. Angered over Disney’s criticism of a Florida education law that opponents called anti-gay — and seizing on an opportunity to score political points with supporters — DeSantis took over the tax district, appointing a new board and ending the company’s long-held ability to self-govern Disney World as if it were a county.

Before the takeover took effect, however, Disney signed contracts — quietly, but in publicly advertised meetings — to lock in development plans.

The tax district, created in 1967, was a crucial tool for developing Disney World because it gave Disney unusual control over building permits, fire protection, policing, road maintenance and development planning. Today, Disney World comprises four theme parks, two water parks and 18 Disney-owned hotels with a combined 267 swimming pools.

The growth plan that Disney locked into place before DeSantis and his allies took over the district — and that will now be renegotiated — involves the possible construction of 14,000 additional hotel rooms, a fifth major theme park and three small parks. The company has said it earmarked more than $17 billion in spending to fuel growth at the resort over the next decade, expansion that would create an estimated 13,000 jobs at the company.

Calling DeSantis “anti-business” for his campaign against the company, Disney last year pulled the plug on an office complex that was scheduled for construction in Orlando at a cost of roughly $1 billion. It would have added more than 2,000 Disney jobs in the region, with $120,000 as the average salary, according to an estimate from the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.