Not dead, but still voting

Dozens of people identified as potentially dead voters say they are very much alive.

Posted — Updated"The people at the polls introduced me and said, 'This is Carolyn and this is her first time to vote,'" recalled the retired special education teacher.

Perry, who has been registered to vote in North Carolina since at least 1975, according to election records, was dismayed to receive a letter this month from the Wake County Board of Elections suggesting she may no longer be qualified to vote because she might be dead.

"My initial reaction? I was mad as hell," Perry said Monday morning.

"We're not really interested in partisan politics," said Jay DeLancy, a retired Air Force officer and director of Voter Integrity Project. "As an organization, we try to eliminate those kinds of biases in our research."

Since DeLancy's group gave those names of potentially dead voters to the State Board of Elections, state and county elections officials have been investigating the list. Some names were already removed through regular list maintenance procedures, officials say. Others required further investigation. In Wake County, letters went to the families of 148 possibly deceased voters.

So far, 42 have sounded off that they're still among the living.

Despite DeLancy's assurances of being nonpartisan, Perry suspects she and others like her were targeted because of her demographic characteristics.

"I'm a senior, and I'm an African-American," she said. "And I'm not registered as the same party they are most likely." Perry is a registered Democrat.

DeLancy denies any partisan targeting. He says his group will soon publish all of the names of people on the voter rolls that they suspect are dead so that the general public can help with their research. And, he said, further research is likely to show that there are some counties where dead people have been recorded as having voted.

Election officials say they've yet to run across anything untoward.

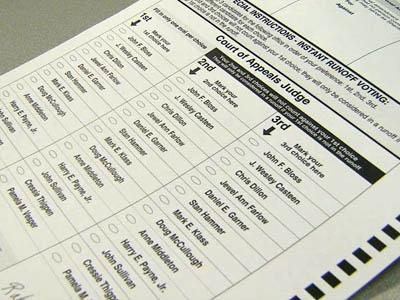

DeLancy's group has sent Wake County two batches of potentially dead voters, Sims said. In one batch, three voters had cast ballots in elections where they died before Election Day – quite legally. Every year, a handful of voters cast ballots through the mail or during in-person early voting and then die before the election is over.

Emails from the State Board of Election detailed other quirks with DeLancy's data. In one Catawba County case, a clerical error conflated a son and a father with the same name.

One problem DeLancy's group faces is that dates of birth reported to boards of elections are not public records. State and local elections boards may provide only somebody's age. That makes a precise, definitive match impossible in many cases. But even exact birthdays may not help in all situations.

Sims said there are examples in Wake County of voters who share the same names and same dates of birth but who are entirely different people.

Election officials say their experiences with DeLancy's group have not been entirely bad. For example, to handle the deluge of cross-checking necessary, Wake County obtained software from the Register of Deeds office that allows for instant check of Wake County death records, Sims said. This can now supplement the once-per-month purge the office already undertook.

Gary Bartlett, director of the State Board of Elections, said state officials discovered that the Department of Health and Human Services wasn't reporting some deaths that occurred out of state to elections officials. Those voters are now being investigated, he said.

But Bartlett adds that neither the state nor any of the county boards have yet discovered someone who voted when they should not have as a result of the Voter Integrity Project's submission. Bartlett says he doesn't rule out the possibility it could happen, but he points out that election officials have access to Social Security numbers, birthdays and drivers license numbers that citizen groups cannot legally get. All of those pieces of information have been used to differentiate between those who are really dead and those who are expected to show up at the polls this November, he said.

"The takeaway so far is that our lists are pretty good," Bartlett said.

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.