Which liar will Edwards jurors believe?

John Edwards committed many sins but didn't break the law in covering up his affair and illegitimate child, the lead lawyer for the two-time presidential candidate said Thursday in his closing argument.

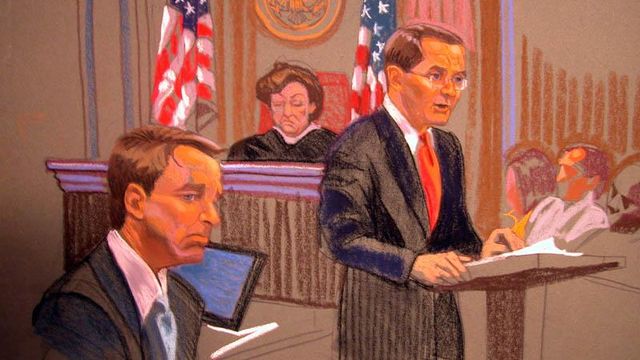

Posted — UpdatedDefense attorney Abbe Lowell pointed out to jurors that the Bible and the book containing federal statutes don't sit side by side in the courtroom because they hold people to different standards.

"This is a case that should define the difference between someone committing a wrong and committing a crime ... between committing sins and a felony," Lowell said.

Edwards is charged with devising a plan to use almost $1 million from two wealthy donors to hide his pregnant mistress, Rielle Hunter, as he ran for the White House in 2008. He faces up to 30 years in prison if convicted on all six charges.

Jurors are expected to begin deliberating his fate Friday morning.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Robert Higdon led jurors on Thursday morning through the odyssey that wound up in front of them in federal court, calling the affair the "seeds of destruction" for Edwards and noting that the resulting weeds eventually "choked his campaign."

Higdon recapped for jurors how former Edwards aide Andrew Young helped hide the affair for a long time and how Virginia heiress Rachel "Bunny" Mellon and Texas trial lawyer Fred Baron were eventually recruited to send money to Young for Hunter's personal expenses and medical care.

"It was one thing to hide an affair. It was something altogether different to hide a pregnancy and a child," he said in his closing argument.

Mellon was a fervent supporter of Edwards – Higdon said her desire for Edwards to be president was exceeded only by the candidate himself – and Baron was a long-time friend who believed having a fellow trial lawyer in a position of power in Washington, D.C., would be helpful, according to the prosecution.

"(Mellon) wanted John Edwards to be elected president, and she was willing to work around those pesky government restrictions to make it happen," Higdon said, referring to the limits on campaign contributions. "Clearly, Mr. Baron, like Mrs. Mellon, was willing to do whatever it took."

Lowell countered by arguing that the payments weren't campaign contributions, only personal gifts to help Edwards hide his ongoing affair from his cancer-stricken wife, who had exploded in a rage when she first learned of his infidelity.

"John Edwards has and always had the means to pay for Rielle Hunter's expenses," he said. "(This money) was not for the purposes of getting around campaign laws. It was for getting around Mrs. Edwards."

Edwards told Young that he had consulted campaign finance experts who had assured him that the money was legal, Lowell said. A former Federal Elections Commission chairman also testified that the agency never contemplated third-party payments designed to hide an affair to be campaign contributions.

Because Edwards believed the payments were legal, Lowell said, jurors cannot find him guilty of knowingly breaking the law.

The defense also pointed the finger at Young, painting him as the mastermind of the scheme, which Lowell said was solely to allow the Youngs to build an upscale home, take trips to resorts and live beyond their means.

Citing the prosecution's claim in their opening statement four weeks ago that Edwards would repeatedly "deny, deceive and manipulate" to keep both his affair and his campaign going, Lowell said the former U.S. senator did it only to protect his family.

"The Youngs deny, deceive and manipulate for money and to live a lifestyle they didn't earn," he said, noting that they "blew through" $1 million in little more than a year.

David Harbach, a U.S. Department of Justice attorney prosecuting the case, scoffed at the notion that Young concocted the cover-up.

"This notion that Mr. Young was in charge and Mr. Edwards was only along for the ride, doesn't that seem a little backward to you?" Harbach asked jurors in his rebuttal to Lowell's argument. "Andrew Young did all this? Andrew Young? That's nonsense."

Lowell highlighted inconsistencies in Young's testimony and the lies that he had already admitted telling. Jurors should be wary of believing anything he said, the attorney argued.

"He just lied over and over again, and it didn't matter if it was big or small," Lowell said. "There's nothing he won't lie about – nothing."

Harbach responded by telling jurors to remember who's on trial and noting that Edwards picked Young for the scheme.

"This is the perfect fall guy," he said of Young. "He's not that smart. The people on the campaign don't like him, and most important, nobody's going to take this guy's word."

Higdon told jurors that federal campaign laws exist to level the playing field between the rich and powerful and the lowly and vulnerable – the two Americas that Edwards always railed against on the campaign trail.

Edwards had been burned once before by the laws, when he was publicly ridiculed for spending $400 in campaign money on a haircut, Higdon said. So, he was ready to break the rules when it came to keeping his affair secret.

"John Edwards forgot his own rhetoric," the prosecutor said. "He had no problem dividing the two Americas when it served his own purposes."

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.