Edwards defense picks apart ex-aide's credibility

John Edwards' defense team began picking apart Wednesday the credibility of a former top aide who is the government's star witness in the campaign finance violations case against the two-time Democratic presidential candidate.

Posted — UpdatedEdwards, a former U.S. senator from North Carolina, is charged with conspiracy, filing false campaign reports and four counts of accepting illegal campaign contributions in connection with the nearly $1 million two donors secretly paid in 2007-08 to hide Edwards' pregnant mistress, Rielle Hunter, as he ran for the White House.

Andrew Young spent his third day on the witness stand Wednesday. Young, who was once a close confidant of Edwards and initially claimed to be the father of Hunter's baby to prevent the media from discovering Edwards' affair, was the conduit for many of the secret payments.

The defense has suggested to jurors that Young devised the scheme to get the bulk of the money from Rachel "Bunny" Mellon, an elderly heiress in Virginia, to finance a lavish lifestyle and that Edwards knew nothing about it. The rest of the money was a gift from Texas trial lawyer Fred Baron, who was Edwards' campaign finance chairman, and wasn't a political contribution, according to the defense.

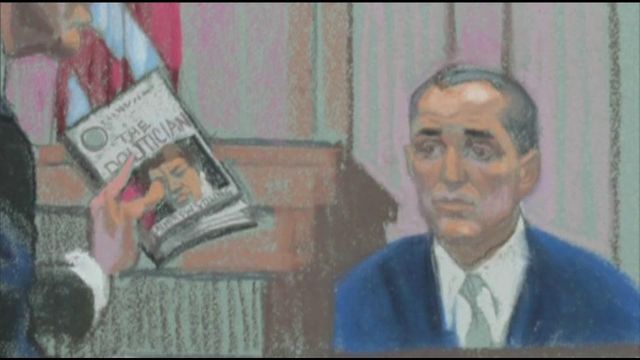

Defense lawyer Abbe Lowell highlighted inconsistencies in Young's testimony, comparing it with "The Politician," his 2010 tell-all book about Edwards' affair and failed campaign, as well as interviews he gave while promoting the book, statements to government investigators and his testimony to a federal grand jury.

"Isn't it true that, in each and every one of those occasions, you lied about critical facts in this case?" Lowell asked Young early on in nearly three hours of bruising cross-examination.

"No, sir," Young replied.

Lowell picked at Young's statements about everything from his role in the operation of Edwards' Senate office to his work for a nonprofit linked to the presidential campaign to his recollection of his first encounter with Hunter.

"Didn't you purposefully exaggerate so many of those stories (about Hunter) to make a better story for yourself?" Lowell asked.

"No, sir," Young replied.

Young grudgingly gave ground during the questioning, and the slow-moving, combative exchanges even exasperated U.S. District Judge Catherine Eagles at one point.

"Do you have a question for him?" Eagles asked Lowell, prompting him to move on.

Lowell painted Young as a sycophant who was so enamored of Edwards that he tried to emulate the style of home the candidate built in Chapel Hill and even used the same dentist. Young then tried to use his knowledge of the affair as leverage against Edwards to ensure financial stability for his family, the lawyer asserted.

Once Edwards' presidential bid ended and the affair was publicized, Young lost his leverage and began making derogatory statements about Edwards to anyone who would listen, Lowell said.

"You really hate him, don't you?" Lowell asked.

"I have mixed feelings," Young replied.

Earlier Wednesday, Young detailed for prosecutors how his decade-long relationship with Edwards quickly crumbled after Hunter's daughter was born in February 2008.

At the time, Young and his family were living in hiding with Hunter in California while Edwards, who suspended his campaign weeks earlier, continued trying to secure a prominent position in the administration of the eventual Democratic nominee.

Young said Edwards cut off contact with him after learning of the child's birth. So, Young turned to Baron, who was paying for their expenses in California, to express his frustration with the situation – Young's wife and Hunter argued frequently, he said – and his concerns that Edwards would live up to his promise to help him financially for covering up the affair.

Edwards' campaign staffers had ruined his professional reputation, Young said, and he feared he would never find a job if Edwards didn't create one for him at a planned anti-poverty foundation.

Baron reassured him and asked him to hold on until August, when the Democratic National Convention would sort out Edwards' future.

"'You guys have the most important job in the campaign, so take a deep breath and do the best job you can,'" Young recalled Baron, who died of cancer in late 2008, telling him.

Young said Baron told him on several occasions that he would take care of all the finances, and Young provided him with an itemized list of expenses that he had been spending on Hunter.

Federal prosecutors showed the list to jurors. It included a BMW, a $2,700-a-month rental home in Chatham County, furnishings for the home, prenatal care, groceries and flights and accommodations so she could meet Edwards.

Young said he never told Baron about checks that he was receiving from Mellon because Edwards had told him that Baron would only support him while he was a viable candidate for a top job in the next administration.

Baron's money "was the short-term solution while Bunny was the long-term solution" to Hunter, Young testified.

Mellon fervently believed Edwards was born to be president and had pledged to Young that she would provide up to $1.2 million to help with expenses to ensure his election.

After several months without hearing from Edwards, Young said that Baron arranged for him to meet Edwards at a Washington, D.C., hotel in June 2008. There, he said, they had in a heated exchange in which they almost came to blows and Young stormed out of the room.

Young said that Edwards called him back into the room and again promised to help him.

"He said he loved me and that I knew he would never abandon me," Young testified, adding that he had "serious doubts" that Edwards would follow through with financial support.

During the subsequent weeks, he said, there were discussions between Young, Edwards and Mellon about her providing up to $70 million for the anti-poverty foundation.

After Edwards admitted on national television in August 2008 that he had an affair, Young said, everything came crashing down.

During a meeting with Edwards on a deserted road in rural Orange County, Edwards told him that Mellon's lawyer and accountant started questioning checks she was sending to Young through her interior decorator, and Edwards said he didn't know anything about the checks.

Young said that contradicted Edwards' earlier assurances that the payments for Hunter were legal, non-campaign expenses.

"If he said he didn't know, what he told me about them being legal wasn't true," Young testified.

Edwards also said during the meeting that the foundation wasn't going to happen. At that point, he said, he told Edwards he had evidence about the cover-up and would "do something about it" if Edwards didn't financially support his family.

"You can't hurt me, Andrew. You can't hurt me," Young quoted Edwards as saying as they ended the last encounter they would have until Young took the witness stand on Monday.

The defense is expected to continue its cross-examination of Young on Thursday.

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.