NC superintendents' contracts packed with perks

North Carolina superintendents are among the highest paid public school employees in the state, but their six-figure salaries aren't the only way they're compensated. Many receive thousands of dollars in bonuses each year, and some get special perks, such as cars, gym memberships, money for mortgage payments and extra vacation time.

Posted — UpdatedRent-free house seals the deal for Currituck superintendent

In Currituck County, a coastal community that serves about 3,900 public school students, school board leaders tried to lure Allison Sholar to their school system in June 2011, but their salary offer wasn't cutting it.

"They were only offering me what I was making (as a superintendent) in Pender County. It wasn't going to be cost-effective," Sholar said in recent interview with WRAL.com.

Currituck stepped up its offer and agreed to let Sholar live rent-free in a house on school property, previously used by superintendents, principals and teachers. As part of the agreement, the board also promised to pay her utilities, including phone service, and allow her three dogs – a black Labrador and two mixed-breeds – to live in the house.

Before agreeing to the new offer, Sholar asked the board to take it one step further – she wanted a fenced-in area where her dogs could play and not interrupt nearby school children. The board agreed and paid $4,284 to have a fence installed.

On Jan. 14 of this year, the board noted Sholar's decision to leave the house and amended her contract to pay her an extra $1,200 a month since she gave up the benefit of living in the house, which has since been turned into office space.

Sholar says her unique contract is a testament to Currituck County's close-knit, caring community and says locals wouldn't be surprised by her benefits.

"I guess Currituck County was trying to be really creative with what they were offering," she said. "It's indicative of a family atmosphere and people looking out for each other. I was appreciative of that opportunity."

Dare superintendent: 'It's expensive to move'

About 40 miles south of Currituck County, another unique superintendent contract was in the works in May 2000. Dare County Schools had narrowed its applicants from seven semifinalists to three and finally chose Sue Burgess, who was working as the superintendent in Spotsylvania County Schools in Virginia at the time.

"Relocation is tricky for superintendents because you have a house. If you can't sell it, how can you make two house payments?" Burgess said. "It's expensive to move from one state to another."

"It was certainly a help to me to have six months' assistance. I would have liked to have more than six months, but six months helped me," Burgess said.

The board also paid for four house hunting trips for Burgess and her husband, including their travel and lodging expenses, and paid $10,000 in closing costs on the house they purchased in Dare County. The contract also covered Burgess' relocation fees, including packing, moving and temporary storage of her household items.

"It reduced the financial burden of relocating," Burgess said. "It’s a lot more expensive to live in Dare County than Spotsylvania."

Hyde superintendent: 'My, what an error'

"My, what an error. My monthly pay is $9,166.67," Latimore wrote. "I can only attribute that figure to a typo. Thank you for catching that error. A salary of that magnitude for such a rural, small, and economically challenged community would be totally unacceptable and unprofessional."

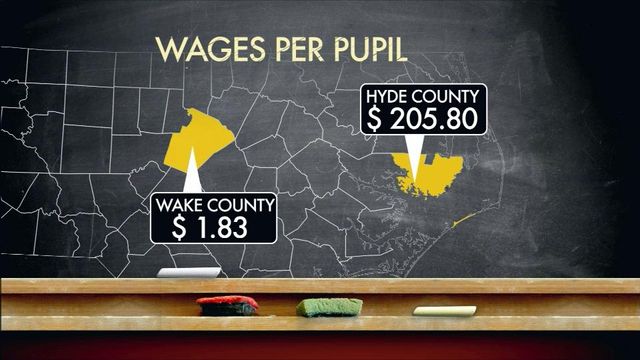

Meanwhile, Wake County's superintendent – the second-highest paid superintendent in the state at $275,000 – is at the bottom of the list, making about $1.83 for each of his 150,544 students.

"It all depends on how bad the board wants that person," Schafer said. "The idea is to attract the best superintendent you can."

Negotiating salary, contract length, travel allowances and moving expenses are fairly common, according to Schafer, but not every superintendent focuses on pay.

"Sometimes, instead of salary, people want money paid into an annuity, usually people closer to retirement," she said. Others might ask for perks that benefit their family, such as health coverage for a spouse and children.

Mooresville superintendent's contract focuses on family

The board granted him 20 extra vacation days, more than most superintendents receive.

"I wanted to drive back and forth," Edwards said, noting that he made the seven- to eight-hour drive because he wanted to watch his children's soccer and T-ball games.

Now in his sixth year with Mooresville schools, Edwards has negotiated extra perks and extensions to his contract each year, which will keep him with the school system through June 30, 2017.

Last year, the board agreed to increase his extra vacation days to 22, more than any other superintendent in the state. Edwards says he mostly uses those days to help care for sick family members.

"It's really family for me that's the motivation," he said.

This past June, the board added a health care benefits clause to Edwards' contract that reimburses him up to $5,000 per year to help cover any uninsured medical, dental and eye care bills for himself, his wife and children.

It's benefits like that, Edwards says, that make him want to stay with the Mooresville school district, despite being heavily recruited this year after he was named the national Superintendent of the Year by the American Association of School Administrators.

"I feel lucky to be here. I’m thankful," Edwards said. "As you get older, you realize if you’re in a good situation you should be grateful for it."

Wake superintendent asks for security clause

When the Wake County Public School System hired its new superintendent this summer, the school board stuck with its standard contract, which it had used for previous superintendents, including Tony Tata and Del Burns.

"We don’t really deviate too much from that model or that framework," said school board Chairman Keith Sutton, who handled most of the negotiations over email.

"That was the first time I had ever heard of it," Sutton said. "He's never used it, (but) it's nice to have if you need it."

Merrill, who declined an interview for this story, had a similar clause in his contract while serving as superintendent with Virginia Beach City Public Schools, according to Sutton. He is one of four superintendents in North Carolina with a security clause. The other three are Caldwell, Guilford and Rockingham county schools.

Besides a security detail, the Wake school board also agreed to provide Merrill with other benefits, including $900 per month for travel expenses, 12 extra vacation days per year and reimbursement for a life insurance policy worth $550,000 – two times his salary.

"I don’t know that there’s too much that’s in there that’s creative. It’s pretty bland," Sutton said. "We try to stay away from (creative perks) and just be good stewards of the taxpayer dollars."

State superintendent: We need to attract the most competent people

As leader of the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, State Superintendent June Atkinson is responsible for verifying that each local superintendent is qualified for the job.

As an elected official, she is the only superintendent in the state without a contract. Her annual salary of $124,676 is set by the General Assembly and is lower than nearly 80 percent of the local superintendents' salaries.

"That has always been a discussion point ... how can you get local superintendents to run (for state superintendent) when there is a difference in salary?" Atkinson said.

Despite her difference in pay, she says local superintendents lead complicated enterprises, which she compares to CEOs running private companies.

"(Negotiating skills) reflect what will be covered in some of the contracts," Atkinson said. "It would mirror CEOs in the private sector negotiating what’s important for them ... We need to make sure we can attract the most competent people we can, and money is a part of that."

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.