Challenge to DOT's protected highway corridors before Supreme Court

The future of a state law that allows transportation officials to hold down prices on land needed for future highways, even if they don't pay property owners for decades, was left up to North Carolina's Supreme Court on Tuesday.

Posted — UpdatedThe law has left thousands of property owners in Wake, Johnston, Forsyth, Cumberland, Cleveland and other counties stuck with real estate unlikely to appreciate in value, and dozens of them filled the court's chambers as the justices heard arguments.

"It’s made an old man of me," said Gene Kirby, who has battled the state for more than three decades over developing land he owns in High Point.

"It’s upsetting to own a piece of property you can’t do what you want to with," Kirby said. "The state has set the rules, and we have to like it or lump it."

Attorney Matthew Bryant, who represents Kirby and other property owners, said the law, known as the Map Act, unfairly cheats owners out of money their land could get on the open market in order to give taxpayers a better deal.

"The state has imposed indefinite, perpetual development restrictions on these owners' properties for the sole and single purpose of price control," Bryant told the justices.

The Map Act, named because it prohibits new construction or subdividing property appearing on maps showing highway routes, is so far-reaching it dwarfs other government powers such as zoning restrictions that limit private property, he said. Opponents say North Carolina's law goes further than similar regulations in about a dozen states, from Nebraska to New Jersey.

"These states have all recognized there's a difference – a constitutional difference – between telling an owner he can't build too close to a neighbor's house and telling that same owner you can't build there because some day, in the unannounced future, at some unknown time, the state is going to want that property," Bryant argued.

The price freeze allows state highway builders to stretch out the time until construction, leaving people like 73-year-old Walter Simpkins in limbo. He's been unable to cash in on rising property values in growing Wake County because of highway plans targeting his 40-acre farm off Ten-Ten Road since 1996, he said.

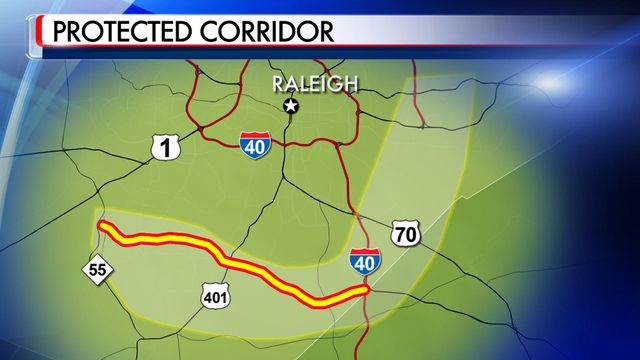

The southern sections of the N.C. Highway 540 toll road has been held up for two decades due to environmental considerations and lack of money.

"I haven’t been able to move on with my life because they’ve got my hands tied," Simpkins said after the court hearing. "I can’t develop it, sell it or do anything with it until they decide what they want to do with it – if I’m still living at that time."

A lower court ruled in the lawsuit last year that the state had effectively taken private property along a planned route for a Forsyth County highway when its map froze development nearly two decades ago.

The years of lost land value could cost taxpayers $200 million or more to pay property owners If the decision isn't overturned by the Supreme Court, state Transportation Secretary Nick Tennyson said last year.

The state House voted last year to repeal the Map Act, but the legislation stalled in the Senate.

Solicitor General John Maddrey, the state's top appeals lawyer, argued Tuesday that the Map Act is as legitimate as zoning that limits conflicts between industry and homeowners or rules banning construction in flood-prone areas. The Map Act merely regulates a property's uses, he said.

"They're designed to harmonize the public's need in the future with what a private property owner can do with his or her property," Maddrey said, adding that property owners get a tax break because the land remains undeveloped.

For Pat Johnson, such discounts don't pay for the time she lost with her husband, who died of cancer in late 2014.

"We should’ve spent the last 10 years on the beach somewhere instead of fighting this crap," said Johnson, who owns 60 acres near the intersection of Kildaire Farm and Holly Springs roads in the path of N.C. 540. "You can put a man on the moon in 10 years, but you can’t build a road in 20. That’s crazy."

The Supreme Court's ruling could take several months.

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by WRAL.com and the Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.