Mental health system 'failed blatantly' in mass shootings

Monday's shooting rampage at the Washington Navy Yard that left 13 people dead is the latest example of a gunman suffering from a mental illness opening fire on a crowd of people.

Posted — UpdatedAaron Alexis, a former Naval Reservist, had been treated since August by the Veterans Administration for problems that included paranoia, voices in his head and a sleep disorder. Officials said, however, that Alexis, 34, never expressed homicidal thoughts, so the Navy never declared him unfit, which would have voided his security clearance as a contractor at the Navy Yard.

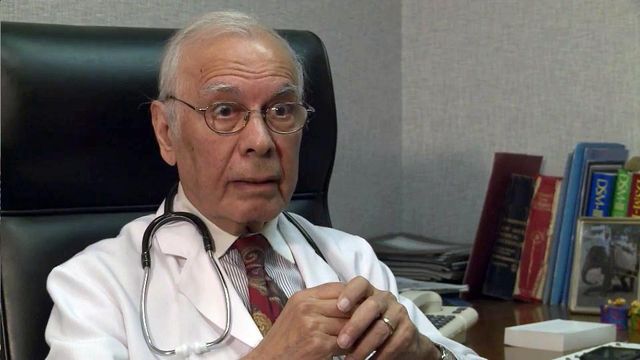

Dr. Assad Meymandi, a Raleigh psychiatrist, said the nation's mental health system has "failed blatantly" by not providing the necessary care to mentally ill people such as Alexis.

"I saw three patients this morning. I didn't know what to do with them," Meymandi said Wednesday, noting there aren't enough in-patient psychiatric beds to treat everyone who needs help.

"If those patients were in treatment, they wouldn't be violent," he said.

Meymandi said the problem has been decades in the making. He noted that, when he received his psychiatric training at Dorothea Dix Hospital in Raleigh in the late 1950s, psychiatric patients received predictable, excellent and accessible care.

"Money was not allocated. The system was not nurtured and developed the way it should be," he said.

Dave Richard, who took over three months ago as director of North Carolina's mental health system, said the state is making progress.

"You'll hear people say we need more money. We also need to focus on the most appropriate things to make our system right," said Richard, former director of mental health advocacy group The Arc of North Carolina.

North Carolina is taking aggressive steps to address crisis issues and the community mental health system, he said.

"We're going in the right direction. We have a long way to go, but I'm confident you're seeing a change in the system and we're creating a kind of system that's sustainable long term," he said.

Meymandi said, however, that the safety net for the most needy isn't there, and the state's history of reforms doesn't inspire confidence that it will be any time soon.

"Pussyfooting around with bureaucracy and patchwork here and a step there – let's see what happens – it won't work," he said. "We need to be seriously dedicated to the cause of taking care of these people."

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.