For secretive companies, your health data means big money

Data mining companies are selling consumer medical information to almost anyone for pennies per name. And experts say there's little protection for consumers interested in safeguarding their privacy.

Posted — UpdatedJust a few weeks ago, she announced to family and friends that she was pregnant.

But thanks to those loyalty cards and other efforts to track data on consumers like her, strangers could have found out she was expecting long before even her closest relatives.

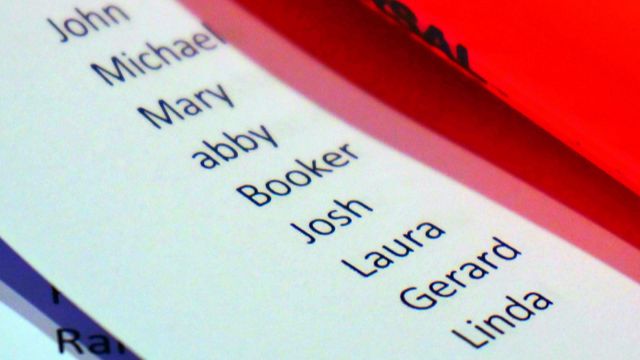

Isaacson's name was one of thousands WRAL reporters were able to purchase in an investigation into data mining companies. The lists, compiled and sold to everyone from corporate marketers to politicians, include names, addresses and health information gleaned from purchasing patterns.

Experts say there is little protection for ordinary consumers, many of whom don't know data about their battles with diabetes, high blood pressure, cancer and even depression are being sold for just pennies per person.

"It is actually shocking and scary that somebody can buy my information," Isaacson said.

A lot of what data mining companies compile starts with long privacy policies most consumers don't read when they sign up for online services from retailers, social media applications or banks. Many of these policies grant companies the right to sell consumer information for almost any purpose.

Although federal law protects medical information patients provide to doctors, pharmacists and health insurance companies, what consumers buy or search online might indicate certain health conditions.

That data, although not always accurate, can be incredibly valuable to groups looking to get their products or messages out to the right people.

"Consumers are helpless," Sarah Ludington, a Campbell University law professor who specializes in free speech and privacy, said. "They have almost no legal mechanism for keeping control of their information or for getting an effective remedy if their data has been misused."

But Ludington said in all that time, there's been very little progress toward any sort of regulation over the data mining industry.

"Nothing's changed. That's what surprises me the most," Ludington said. "There isn't yet a meaningful law that protects consumer privacy."

More often than not, Ludington said decisions about how to use this data – and decisions about what to disclose to consumers – are left up to secretive companies with little oversight.

"This is the problem of having no laws. The company that possesses all that information, it's up to them whether they want to let consumers see it or not," Ludington said. "And most of them have said 'no.'"

Ludington said consumers can take steps to protect their information by avoiding online surveys, adjusting privacy settings on their Web browsers and being more aware about using loyalty cards at retailers.

"Think twice when you use your customer loyalty card whether there's anything you don't want people to remember," Ludington said.

That's likely what landed 61-year-old Marilyn Bruner on a list of supposedly pregnant women.

The devoted caretaker of a brightly colored cockatoo named Maggie, Bruner had to think hard before realizing the baby food she buys is probably what led data miners to their incorrect conclusion.

"Maybe that's why they think I'm pregnant," Bruner said. "I buy it for the bird."

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.