Exonerated men face new struggles as they enter modern world

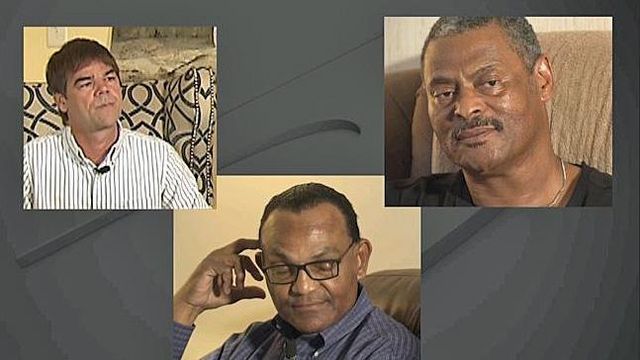

Three men who were convicted of crimes they did not commit are doing their best to make it in a modern world they don't even recognize.

Posted — UpdatedTheresa Newman, a Duke law professor and co-director of the Wrongful Convictions Clinic, says when people are exonerated, they walk out into a new world with no help.

"You get $45, and when you're released on innocence, you walk out," Newman said.

There is no help with housing, employment, transportation, education, mental health or employment.

"They are not sure how to navigate, so sometimes they make missteps when they first get out," Newman said. "Two, it's very difficult to get a job."

Newman, whose work has freed eight people and helped to exonerate six, said their release from prison is more than just a celebration.

It is “a time to respect that it is the beginning of a very long struggle," she said.

"I cannot restore to people who are exonerated the great loss they've suffered and the struggle they have ahead of them. I can assist, and we do assist, but we have to do better."

“You just want your freedom back.”

Dudley, now 60, was convicted of sexually assaulting his then 9-year-old daughter in 1992. The only evidence was her word against his. He has spent the past 24 years telling everybody he was innocent.

"You just want to get out. You want your freedom," he said. "You just want your freedom back."

Dudley’s daughter, Amy Moore, now 33, told a judge her allegations were fictitious. Mental health experts testified that Moore suffers from mental illness and was easily led to make false statements.

Dudley could have avoided prison if he had pleaded guilty in 1992, but then he said he would have been imprisoned by another lie.

He is now waiting on the governor's pardon, which he needs in order to get compensation from the state.

"It was like they threw me out there and said, 'You can either swim or you can sink,' and I definitely can't swim," Dudley said.

Dudley said he has had a tough time since his release securing a job. He also suffers from anxiety and spinal pain.

"When they look at these injuries and they look at my age they say, 'This guy is a liability,'" Dudley said.

During his 23 years and 7 months in prison, he lost his wife and mother. Dudley's sister died shortly after his release.

"I'm not angry," he said. "If I was angry and allowed anger to engulf me, I would still be in bondage to that situation," he said. "What I do is I just choose to let it go and start my life over and live, enjoy life."

Dudley, who lives in Kinston with his brother, has a serious girlfriend and plays guitar in a gospel band at his church.

He said he does not regret the more than two decades he spent behind bars.

"You try to look at the bright side of things," Dudley said. "I don't really care for looking at the negative side of things because I just want to pick up the pieces and move forward."

“I feel like people are looking at me.”

"You think when you do get out, everything is going to be great," Dail said. "Your family will be reunited, everything will just be beautiful ... and there will be no more problems because all of the problems are over with and unfortunately, it's just not the way it works out."

The North Carolina Center on Actual Innocence, and its Director Chris Mumma, helped find the DNA evidence that exonerated Dail and ultimately led to his release.

In October 2007, Dail was pardoned by then-Gov. Mike Easley and was compensated $750,000. He also won a civil lawsuit for $7.5 million.

"I would give them back double that money to have my life back," Dail said. “There was no amount of money that was worth what I was put through, me and my family."

Dail said he read a lot while he was incarcerated, but despite his self-educating efforts, it was a different world when he got out.

"I don't even know how to pump gas," Dail said. "There are still 50 things on my phone that I'm sure I'll never know how to use. Everything is different."

Now, he is now working to repair the relationship with his 27-year-old son.

"I did not get to raise my son. My son was 18 years old when I got out," he said. “It is frustrating for him. It is frustrating for me. He was terribly affected by what happened to me as well."

Dail now lives a quiet life in Goldsboro with his two English Bulldogs, Fatback and Biscuit. He said he avoids going out in public.

"I feel like people are looking at me," he said. "This transition has been just as difficult for me, and it still is difficult at times, as it was the transition into prison."

“I came home with the idea of being maximum service to my fellow man.”

In 2012, state investigators re-examined evidence in the case and found that a bloody palm print matched another suspect.

Armstrong’s case started when he wrote to the N.C. Center on Actual Innocence which then referred the case to the Duke University School of Law's Wrongful Convictions Clinic. They then won his release.

Armstrong always maintained his innocence, but before he left prison, one of his prison administrators warned him that his release would come as a shock.

"She was right," he said.

Armstrong was allowed to take some computer classes in prison, but was blocked from taking additional classes because he was told he would never get out.

He lived in a group home, but was able to transition into an apartment, buy a car and land a job at Durham's Freedom House, a treatment facility that specializes in mental health and substance abuse services.

Armstrong was pardoned by then-Gov. Pat McCrory on Dec. 23, 2013, and received $750,000 from the state. He was also awarded $6.42 million from a lawsuit against the City of Greensboro.

He went back to school and earned his associate's degree in substance abuse counseling in July 2014.

"I slept over it, thought about it, prayed about it, and about two weeks later, I decided, you know what, I can do this," he said.

Armstrong has a 40-year-old son, a 28-year-old daughter and a granddaughter in college. He is now working to repair his relationships with them. Most complicated is the relationship he has with his daughter.

"She's holding me responsible for me being gone," he said. "We've had a couple conversations in the last year and I keep telling her it's not my fault and it definitely ain't yours, however, we have to move past this."

Despite being financially sound, Armstrong said he works to help others in need.

"I came home with the idea of being maximum service to my fellow man, and I think I do that every day," he said.

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.